A nine-year-old in a purple wheelchair asks four harmless words—“May I sit here?”—and the entire diner goes silent. Nobody approaches Jackson “Reaper” Cole, the Hells Angel with a scarred face and a past that kills conversation. But Emma doesn’t flinch… and her sketchbook holds a drawing that cracks open the grief he’s buried for four years. Then the state rips her away “for her safety.” Two nights later, a group home erupts in flames—and Emma is trapped upstairs. Reaper has seconds to choose: obey the law… or run into fire and become the monster they fear.

The Riverside Diner had been built long before the interstate rerouted most of the traffic away from town. Its chrome had dulled, its neon sign flickered more than it glowed, and the vinyl on the booths had been patched so many times it looked like a quilt. Still, to the people of Riverside, it was the center of a slowly shrinking universe—a place where coffee was always hot, gossip traveled faster than Wi-Fi, and the regulars sat at their same tables so often their weight had left permanent impressions in the cushions.

In the far corner, where the window overlooked the parking lot and the river beyond, sat the only man nobody ever tried to claim as “theirs.”

Jackson “Reaper” Cole.

He occupied that corner booth the way a storm cloud occupies the horizon—permanently, darkly, and with a kind of quiet threat that made people lower their voices when they passed. A battered leather cut hung from his shoulders, the patches stitched across the back a language most folks in Riverside didn’t speak but instinctively understood. The “Hells Angels” rocker curved over a grinning skull. Below it, smaller patches: “1%” in red and white. “Sergeant-at-Arms.” A row of other rectangles that meant nothing to Maggie, the waitress, except that this man lived in a world where violence wasn’t theoretical.

He had been coming in for four years, always at the same time—6:30 a.m., just as the sun lit the river in pale gold—and always ordering the same thing: black coffee and a bacon skillet, no toast. He never smiled. Never chatted. Never met anyone’s eyes for more than a second or two. He would sit, read his folded newspaper, eat in silence, pay in cash, and ride off on the black Harley parked out front, its exhaust note low and angry.

Maggie, who’d worked the diner for sixteen years and knew every regular’s secrets by the way they stirred sugar into their coffee, kept her distance. She refilled his mug with the cautious respect one might show a caged but restless animal. Over time, she’d learned a few things despite his silence. He tipped generously. He flinched at sudden loud noises—the slam of a dropped tray, the crack of a cook shouting through the window. And when someone laughed too loudly behind him, his shoulders tightened just a fraction.

But mostly, he was stone. Granite. A man carved out of something harder than ordinary flesh.

Which was why the question hit the room like a glass dropped on tile.

“May I sit here?”

The voice was small, high, and incongruous with the smell of burnt coffee and fried eggs. For a second nobody registered it had come from anywhere at all, like the diner itself had suddenly spoken. Then Maggie turned and saw the girl in the purple wheelchair, her small hands resting lightly on the rims, her dark eyes focused like she’d practiced this exact moment a thousand times.

Behind her, an elderly couple hovered, their posture that specific mix of protectiveness and fatigue that Maggie recognized immediately: people who had been doing everything they could for longer than anyone had helped them.

“Excuse me, miss,” the girl said, a little louder this time, because no one had answered the first question.

Maggie wiped her hands on her apron. She glanced automatically toward the corner booth. Reaper’s coffee cup hung suspended halfway to his lips, his eyes fixed on the newspaper but no longer reading. The air in the diner changed, grew heavier somehow. Silence spread from his booth outward, swallowing conversations, clinking silverware, even the sizzle from the grill.

“Yes, sweetheart?” Maggie said carefully, moving toward the wheelchair.

The girl’s chair was plastered with stickers—stars, moons, faded unicorns, a crooked superhero logo. Her hair was pulled back in a ponytail that had started the day neat and had clearly given up somewhere between home and the diner. Her sneakers were bright yellow, the kind of impractical color only kids and optimists chose.

“May I sit there?” she asked, and this time she pointed.

At the booth. At him.

Maggie’s heart dropped into her shoes.

“Oh, honey,” she said gently, already reaching for the handles of the chair. “How about I get you and your grandparents a nice table over here by the window? You can see the river. That’s a good spot.”

“May I sit there?” the girl repeated, like Maggie hadn’t spoken at all. She didn’t look at Maggie, didn’t look at the rest of the room watching, hardly seemed aware of the tension icing the air. Her gaze was locked on the biker in the corner.

On Jackson “Reaper” Cole.

The elderly woman behind her—white hair pinned into a bun that had partially escaped, cardigan buttoned crooked—leaned down urgently. “Emma,” she whispered, voice tight. “We can sit over here, sweetheart. Please. Don’t bother the man.”

But Emma kept her eyes forward.

“May I sit with you, please?” she asked, directing the question to Reaper now. Her hands trembled slightly on the wheels of her chair, but her voice, though soft, didn’t crack. “I have something to show you.”

At the counter, a trucker with a gut like he was smuggling a watermelon beneath his flannel shirt set his coffee down, uneasy. Near the window, two teenagers in work overalls froze mid-bite. Even the cook pushed his cap back and leaned to get a look through the pass.

Maggie swallowed. Her fingers tightened on her order pad.

She knew certain things. She knew the wreck four years ago had almost killed him. Knew his wife had died in it. Knew he’d walked away with permanent damage to his throat, a ragged scar across his forehead, and a silence that had settled over him like a vow. She knew his club history was thick with violence, though details were always rumor and never fact. She knew the cops kept tabs on him. She knew trouble followed men like that the way flies followed trash.

What she didn’t know was what he would do if a child poked at whatever he kept locked so tightly inside.

The newspaper rustled. Reaper lifted his eyes.

They were gray, Maggie realized, not cold blue like she’d always imagined. Gray like river stone. Gray like the sky just before a storm broke. They moved from the girl to the grandparents, to Maggie, then down to the wheelchair. His gaze paused on the stickers, on the small scuffs at the bottom where the frame had clearly met every curb and doorway between here and wherever she lived.

His jaw flexed once. His fingers drummed a single sharp beat against the ceramic mug, that tell Maggie had come to recognize as irritation or agitation. Then they went still.

“Emma,” the elderly woman pleaded again. “Come on now. We’ll find another seat. I’m so sorry, sir, she doesn’t mean to—”

The words that came out of Reaper’s mouth sounded like they had been dragged over gravel and broken glass.

“Yeah,” he said.

Just that. One syllable. Rasped and low and shocking.

The room reacted as one, a subtle, collective flinch. Reaper didn’t talk. Not here. Not anywhere that anyone had noticed. Old rumors about damaged vocal cords whispered through the diner like ghosts.

He folded his newspaper with deliberate care and slid his coffee cup to the side, away from the space in front of him. Without another word, he shifted the salt and pepper shakers closer to the wall, clearing the section of table across from him.

Emma’s face lit up like someone had flipped a switch inside her.

“Thank you,” she said, a little breathless with relief. She spun her wheels expertly, angling the chair so she could slip between tables, plastic footrests narrowly missing a chair leg someone hurriedly pulled out of the way. Her grandparents stepped aside, looking pale and torn and powerless.

The old man—bent at the shoulders but still broad enough to suggest younger strength—gave Reaper an apologetic nod as the girl rolled past. “We’re sorry to disturb you,” he started. “She can sit—”

The biker’s eyes flicked to his, a warning that needed no words. The old man swallowed his sentence and guided his wife toward the booth across the aisle instead, settling where they could reach Emma quickly if something went wrong.

It looked, Maggie thought, like they’d just watched their granddaughter step into a lion’s cage at the zoo.

Emma parked her wheelchair at the end of the booth, facing Reaper. She popped the brake with a practiced flick and then, with surprising agility, swung herself sideways onto the seat. Her legs, thin beneath her leggings, moved awkwardly but determinedly. Once settled, she reached down, hauled her sketchbook up from a bag hooked on the back of her chair, and slapped it on the table like she’d been invited for show-and-tell.

Reaper studied her. Up close, she was all contradictions—too thin but with cheeks that still held the roundness of childhood, eyes that had seen too much and still managed to gleam with curiosity. There was a faint scar along her jaw, half hidden by a wispy lock of hair, and a constellation of ink smudges along the side of her hand from where she’d gripped a pencil too tightly.

“What’s your name?” she asked, like they were two kids at recess and not a child and a man whose nickname was whispered like a threat around town.

He hesitated. It had been a long time since anyone had asked him that without already knowing the answer.

“Reaper,” he said finally, and even that one word scraped the inside of his throat.

Emma wrinkled her nose. “That’s not a real name. It’s scary.”

He shrugged, a slow lift of one shoulder. “Wasn’t trying,” he rasped. “Just am.”

Someone at the counter snorted quietly and then pretended they hadn’t. Maggie shot them a look that said if they wanted their eggs before lunch, they’d shut up.

Emma tilted her head. She seemed to consider him the way she might study a still life in art class—angles, shadows, negative space. Her gaze lingered on the scar that split his eyebrow and disappeared into his hairline, then on the patch on his vest that read “Sergeant-at-Arms,” then on his hands, big and scarred but still, now, resting on either side of his folded newspaper.

“I don’t think so,” she said after a moment. “I think you’re sad, not scary.”

The statement landed harder than an accusation might have.

Reaper’s fingers tapped once against the table. He didn’t look away, but something closed off in his eyes, like a door slamming shut.

“Sad people sometimes look mean because they’re protecting themselves,” she went on, undeterred. “That’s what my therapist says.”

A few people winced like she’d dropped a curse word instead of something as mundane as “therapist.” In Riverside, you went to church, or you went to the bar. You didn’t go to therapy. Therapy was for people on TV.

Reaper’s hands curled around his mug again. He could feel years compressed into that grip—the hospital room, the beeping machines, Maria’s hand going slack in his. The screams he tried to force through a throat that wouldn’t work right anymore. The way silence had seemed safer than trying to talk and hearing his own voice broken.

“Therapist, huh,” he muttered, the word tasteless in his mouth.

Emma nodded brightly. “Yup. Twice a week. Dr. Abrams. She has a picture of a beach in her office, but if you look veeeery closely—” she narrowed her eyes and leaned forward conspiratorially “—you can see there’s a cigarette butt stuck in the sand. I don’t think she knows. I think that’s funny.”

Despite himself, the corner of Reaper’s mouth twitched. The movement felt foreign. Unpracticed. Like muscles being asked to remember a motion they hadn’t performed in years.

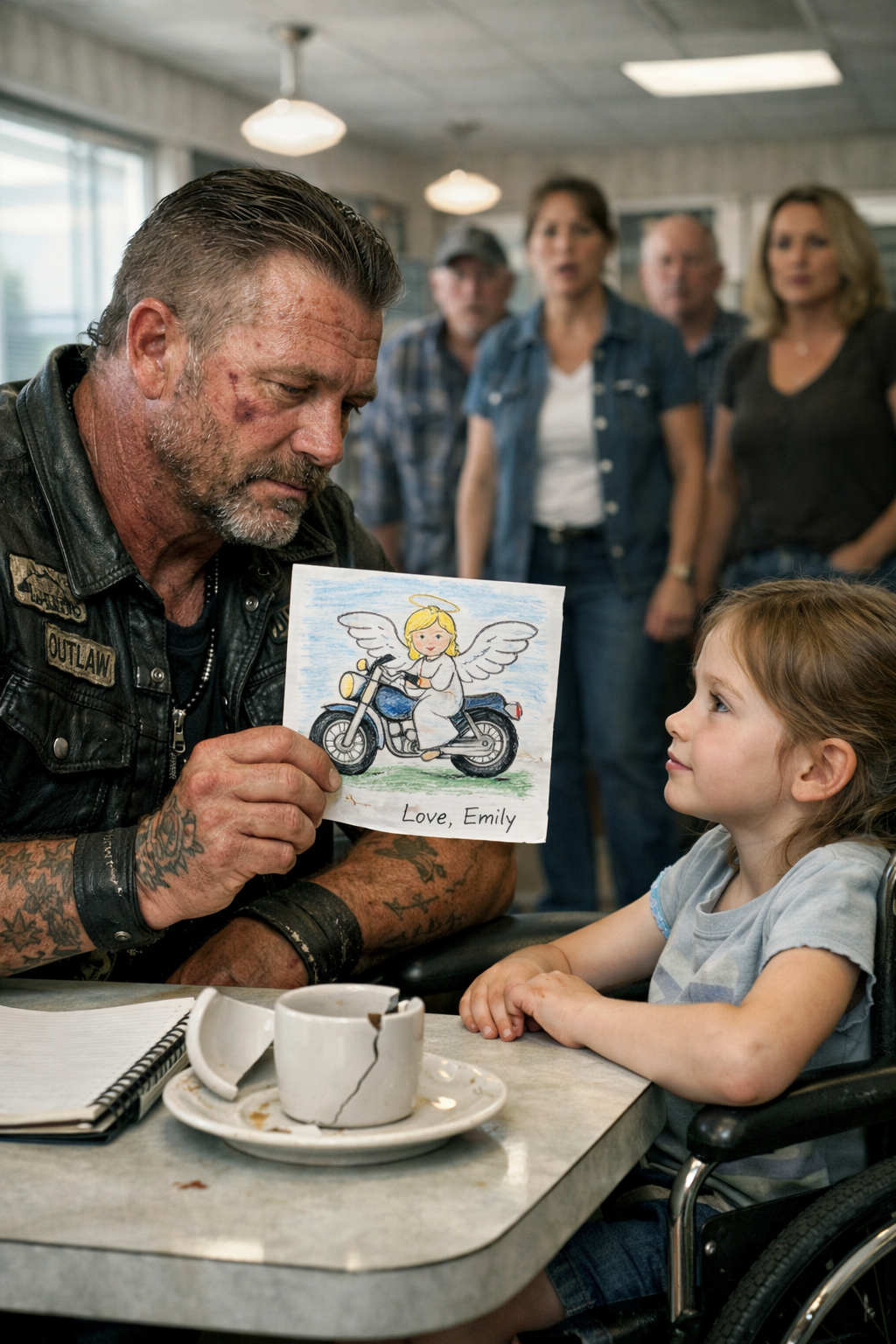

Emma flipped open her sketchbook.

“I drew you,” she announced.

This, Reaper hadn’t expected.

He looked down at the page she turned toward him. Charcoal lines, some tentative and some bold, formed an image that punched the breath from his lungs. It was him, no question—his Harley, the angle of his shoulders, the curve of his cut. She’d even captured the way he hunched slightly when he sat at the diner, as if always braced for impact.

But that wasn’t what froze him.

Behind the figure on the bike, faint but unmistakable, were two sets of wings. Not cartoon angel wings, but delicate, spanning the width of the page, feathers carefully shaded. They weren’t attached to him. They hovered behind him, like guardians.

One was a woman he recognized instantly even in charcoal—Maria, her long hair tied back, her face soft, kind. The other was someone he didn’t know. A woman, younger than Maria had been when she died, her features unfamiliar.

His grip on the mug tightened.

“I’ve drawn you fourteen times,” Emma said quietly, as if confessing a secret. “But this is the best one so far. You always sit right there—” she gestured vaguely toward the booth “—and you always look like you’re thinking about someone who isn’t here. I think about someone too.”

She turned the sketchbook back around and tapped the unfamiliar woman.

“That’s my mama. She died nineteen months ago.” Her voice wobbled just slightly on the number, like she’d been repeating it so long it had become a fact more than a feeling. “I never saw her as an angel, so I made one up. I think they want us to be happy again.”

The mug shattered.

It didn’t slip. It didn’t tip. It exploded in his hand, ceramic cracking under the force of his grip. Coffee spilled across the table, dark liquid racing toward the sketchbook. Emma jerked it back with a gasp, saving the drawing. Maggie was already moving, snatching a towel from the counter.

“Dammit,” Reaper hissed under his breath, jerking his hand back. A thin line of blood welled where a shard had sliced his palm.

“Don’t move, I’ve got it,” Maggie said sharply. Her voice, usually honeyed with small talk, snapped in that way that convinced drunk truckers to give her their keys. She slapped the towel over the mess, soaking up coffee, nudging chunks of ceramic aside.

“Are you okay?” Emma’s eyes were wide. “I didn’t mean to—did I say something wrong?”

Reaper stared at the drawing she held protectively against her chest. His throat felt like it was closing, not from smoke or injury this time, but from something pressing upward from his chest, something he’d forcibly held down for four years.

Maria’s eyes, even in rough charcoal, looked at him the way they had the first time she’d patched him up after a bar fight—equal parts exasperation and love. The invented mama beside her wore a soft half smile, as if she’d just been caught watching her child sleep.

“No,” he managed, his voice even rougher than before. He wiped his bleeding hand on his jeans, ignoring Maggie’s disapproving hiss. “You didn’t do anything wrong, kid.”

Emma gazed at him a moment longer, then seemed to accept that. “Okay,” she said softly. “Good.”

She laid the drawing flat on the dry section of table, careful, like it was something fragile. Like it mattered.

In four years, nothing had gotten under Reaper’s skin the way this tiny human in cartoon sneakers just had. Not cops. Not rival clubs. Not the nightmares. Those he’d learned to live with, to shove into a far corner of his mind like he occupied the corner booth in the diner—alone, untouched.

This girl had wheeled right through the barricades without even noticing they were there.

For the rest of that morning, the diner moved around them. Orders went out. Dishes came back. The cook cursed under his breath at a late delivery. But people composed a respectful distance around the booth, like an invisible perimeter had been set.

Maggie brought Emma a hot chocolate with extra whipped cream without being asked. “On the house,” she said, ignoring the girl’s instinctive reach for some kind of payment and the old woman’s half rise like she should protest.

“Thank you,” Emma replied politely, then turned back to Reaper as if he were the only person in the room.

Over time—minutes stretching into what felt like hours—he realized she’d not just seen him sitting there and impulsively decided to approach. She’d been watching him. Gathering data the way only kids and very observant adults did. Her sketchbook flipped occasionally, revealing other drawings in quick glimpses: the diner’s neon sign reflected in a puddle; the cook leaning on the counter; Maggie laughing with a customer; the river in winter, bare trees clawing at a low sky.

“You draw a lot,” he said at one point, surprising himself with the desire to keep her talking. To hear about something that wasn’t the constant thrum of grief in his own head.

“I have a lot of time,” she replied simply. “I can’t run around, so my brain runs around instead.”

He grunted. “Fair trade.”

She smiled a little. “Is it?”

He didn’t answer. He didn’t know how.

By the time her grandparents wheeled her away, murmuring anxious thanks over their shoulders, something had shifted. Not just for Reaper, though he felt it most acutely, a hairline crack in the ice that had encased his heart since the accident. The whole diner had watched a small miracle unfold, and miracles, even small ones, tended to echo.

Over the next few weeks, the echo grew louder.

It started with proximity—the kind of coincidence that wasn’t. Emma and her grandparents came to the diner more often. At first once a week, then twice. Whenever they walked in, Emma’s eyes went immediately to the corner booth. If Reaper was there, she went to him. If he wasn’t, she settled with her grandparents, but her gaze would keep flicking to the door.

He noticed.

He noticed the way her shoulders would relax when he did walk in. The way she would immediately start rifling through her sketchbook, selecting which drawing to show him. He noticed when she had dark circles under her eyes, when her hair wasn’t brushed quite as neatly, when her grandparents’ hands shook more than usual, fumbling with napkins and silverware.

He noticed, and noticing had never felt so dangerous.

He told himself to keep his distance. To let the small kindness of letting her sit at his booth be the beginning and end of it. But every time she looked at him with that unwavering, assessing gaze, something old and stubborn in him pushed back against the caution.

So he listened.

He listened when she talked about school—the special bus that picked her up, the girls who sometimes made fun of her braces and how she pretended not to care. He listened when she talked about physical therapy—how sometimes progress meant her legs hurt so much at night she had to bite her pillow so her grandparents wouldn’t hear. He listened when she talked about her mama.

“She smelled like oranges,” Emma said once, absentmindedly shading in the background of a drawing of his Harley. “And hair spray. She used to sing really badly in the car. Like, off-key. Grandma says I do it too.”

“You sing?” he asked, an eyebrow lifting.

“When it doesn’t hurt.” She said it matter-of-factly. “My lungs get tired.”

He nodded slowly. “My voice gets tired.”

“I know,” she said. “I can hear it.”

The directness, the lack of pity in her tone, hit him harder than sympathy ever could have. She wasn’t trying to fix him. She was acknowledging a fact, like saying the sky was blue or the floor was sticky because Lou the cook had spilled syrup again.

In return, almost without meaning to, he started to talk.

Not much at first. A sentence here, a word there. He told her about the first time he’d ridden a motorcycle at seventeen and how the wind had felt like the only honest thing in his life. He told her that Maria had loved sunflowers and that they’d been heading home from a concert the night of the accident when a drunk driver had crossed the center line. He told her, haltingly, about waking up in the hospital, his throat on fire, unable to ask where his wife was.

“Did they tell you right away?” Emma asked softly.

“No,” he rasped. “They lied. Said she was in another room. Said I had to get stronger before I saw her. I figured it out when no one would meet my eyes.”

“That’s mean,” Emma said. “To lie about that.”

“They thought they were helping.” He stared into his coffee. “Sometimes people hurt you when they’re trying to help. Sometimes they hurt you ’cause they don’t care at all. Takes a while to learn the difference.”

Emma was quiet for a long moment. The hum of the diner filled the space between them, plates clattering, voices rising and falling. Then she nodded once, decisive.

“Ms. Brennan says she’s helping,” she said, and a shadow crossed her face.

Reaper looked up. “Who’s that?”

“My social worker.” She wrinkled her nose again, but this time it wasn’t in playful distaste. It was something older, warier. “She wears very straight skirts and smiles with just her teeth.”

He didn’t like the way that sounded. “What does she help you with?”

“Stuff,” Emma replied vaguely. “Court. Paperwork. Questions. She asks a lot of questions. She doesn’t like that I draw you.”

Reaper blinked. “She know you draw me?”

Emma nodded. “She came to the diner once.” Her pencil moved faster now, the lines a little sharper. “She saw my sketchbook and said, ‘Who’s that?’ I said, ‘That’s my friend Reaper.’ She made this face like she smelled something bad.”

“Maybe she just smelled Lou’s socks,” Maggie muttered as she passed, dropping a fresh glass of lemonade in front of Emma.

Emma giggled and took a sip. Her expression turned serious again too quickly for someone her age. “She says people in ‘outlaw motorcycle gangs’ are dangerous. She says I shouldn’t ‘engage’ with you.”

“What’d you say?” Reaper asked, voice carefully even.

“I said she shouldn’t use words she doesn’t understand,” Emma said, shrugging. “Then she wrote something down on her clipboard and Grandma looked mad at me in that way where her mouth is smiling but her eyes aren’t.”

Reaper’s jaw tightened. He’d dealt with social workers before, years ago, when he’d been sixteen and his mother had finally OD’d in their tiny apartment. The people with clipboards and tired eyes who talked about “interventions” and “stability” but never stuck around long enough to see whether their plans actually changed anything.

“How often she come around?” he asked.

“Once a month. Sometimes more.” Emma fiddled with her bracelet, a cheap beaded thing that looked like she’d made it herself. “She had a meeting with Grandma and Grandpa last week. I wasn’t supposed to listen, but the vents in our house are very helpful.”

He tried not to smile at that. “What’d you hear?”

“Words like ‘fitness’ and ‘oversight’ and ‘group placement.’” Emma’s shoulders hunched the way his did when something threatened. “I don’t like those words.”

He knew what they meant in her context. He knew, because he’d heard them in his own, years ago, when the state had decided his mother’s chaotic love was more dangerous than no mother at all.

They meant: We might take you away.

He looked at her grandparents, seated a few tables away, the old man stirring his coffee with unnecessary focus, the old woman picking at a muffin she wasn’t really eating. They looked smaller than usual under the fluorescent lights.

He drummed his fingers once against the table.

“You tell your therapist about that?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Emma sighed. “Dr. Abrams says sometimes the system does its best with bad tools. I told her that’s a terrible metaphor because if your tools are bad, you’re just going to break stuff anyway.”

“What she say to that?”

“She said, ‘Point taken.’” Emma smiled faintly. “She says Grandma and Grandpa are fighting for me. But sometimes people with clipboards have more power than people with hearts.”

Reaper’s eyes narrowed. Around them, the diner blurred. He could feel old instincts waking up, muscles of anger and protectiveness flexing inside a body that had grown used to staying very, very still.

“What’s she expect you to do?” he asked, though he already knew.

“Behave,” Emma said, rolling her eyes. “Be ‘cooperative’ and ‘respectful.’ Not get too attached to anybody. She says foster kids get hurt when they get attached.”

Reaper let out a low, rough sound that was more growl than laugh. “Too late on that one, kid.”

“Yeah,” Emma said softly, meeting his gaze head-on. “Too late.”

The thing about unlikely friendships is that they’re like cracks in a dam. At first they’re thin, hairline fractures you can pretend aren’t there. But water—need, love, loneliness—finds those cracks. It seeps in. It widens them, drop by drop, until one day the structure you thought would hold forever gives way.

Reaper didn’t intend to become a fixture in Emma’s life. It happened the way heavy things fall—slowly, then all at once.

He found himself riding past her grandparents’ house more often, his Harley rumbling slowly down their quiet street where one-story homes sat behind chain-link fences and flowerbeds bravely fought the encroaching weeds. He told himself he was just checking things out. Just making sure no one loitered where they didn’t belong. Just making sure Ms. Brennan’s compact car wasn’t parked out front too often.

The first time he stopped, it was because he saw the old man—Emma’s grandfather—standing on a ladder, one foot braced awkwardly on a rung, hammer in hand, trying to patch a leak in the roof. The ladder wobbled visibly from the road.

Reaper pulled over before he could talk himself out of it. He killed the engine, the sudden silence disorienting after the steady roar. The old man looked down, squinting against the afternoon sun.

“Can I help you?” he called, gripping the ladder with one hand.

“Yeah,” Reaper replied, stepping onto the patchy lawn. “You can get off that damn thing before you break your neck.”

The old man’s mouth thinned. “I’ve been fixing this roof since before you were born, son.”

“Don’t doubt it.” Reaper set his hand on the ladder, steadying it with casual strength. “Doesn’t mean you should be doing it now with a hip that probably aches when it rains.”

Suspicion flared in the old man’s eyes, but beneath it was something more complicated. Pride. Fear. Curiosity. And a bone-deep tiredness that reminded Reaper of every too-old man he’d met who’d spent his life working harder than his body was built to work.

“You a doctor now?” the old man grumbled.

“Biker.” Reaper shrugged one shoulder. “We fall off a lot of things. Learn to spot bad ideas.”

A faint chuckle floated from the front porch. Emma was there, small and bright, sitting in her wheelchair with a sketchbook balanced on her lap.

“Told you he’d say it was a bad idea, Grandpa,” she called. “You owe me five dollars.”

“Traitor,” the old man muttered, but his mouth softened. He and Reaper shared a look that felt, unexpectedly, like an exchange of truce flags.

“Fine,” he sighed. “If you’re so smart, you come up here.”

Reaper snorted. “Nah. I’ll bring the roof to me.”

Within an hour, he’d ridden back to the club, loaded his truck with supplies, and returned with two younger prospects in tow, who jumped at the chance to do something that wasn’t cleaning bathrooms or checking tire pressure.

They worked until sundown, replacing rotted sections of wood, laying fresh shingles, sealing leaks. Emma watched from the porch, offering commentary and asking a thousand questions about pitch and nails and why the roof wasn’t flat like in cartoons.

The old man—Henry—grumbled and paced and occasionally held a board in place, but his protests grew half-hearted quickly. At one point, Reaper caught him watching Emma laugh at some idiot joke one of the prospects made, and there was such deep gratitude in his eyes that Reaper had to look away.

At the end of the day, when the last nail was hammered and the tools were loaded back into the truck, Henry reached for his wallet with hands that shook.

“How much?” he asked gruffly.

“Nothing,” Reaper said.

“Nothing is not a number,” Henry shot back. “You used materials. Time. Gas. I may be old, but I’m not a charity case.”

Reaper met his glare evenly. “Then consider it an investment.”

“In what?” the old man demanded.

“The ramp I’m building you next,” Reaper said, jerking his chin toward the porch steps. “That one’s downright criminal for a kid in a chair.”

Emma gasped. “You can build ramps?”

“I can build a lot of things.” He met her delighted gaze and felt something unclench in his chest. “Figure it’s about time you stopped relying on people to haul you up and down like a sack of potatoes.”

“Grandpa is not strong enough to carry a sack of potatoes,” Emma said seriously. “He hurts his back. Grandma says so.”

“Grandma says too much,” Henry muttered, but he didn’t argue when Reaper showed up the next afternoon with lumber and a set of printouts he’d gotten from a slightly confused but ultimately helpful city inspector—blueprints for an ADA-compliant ramp.

They worked for two days. The ramp took shape under Reaper’s hands, the slope calculated, the handrails smooth beneath Emma’s eager fingers as she tried them out.

“This is freedom, you know,” she said the first time she wheeled herself down without assistance, picking up just enough speed to make her ponytail fly behind her. “You’re like… the ramp fairy.”

Reaper snorted. “Do not call me that.”

“The Ramp Reaper,” she amended thoughtfully. “Sounds like a video game.”

“That sounds terrible,” he grumbled, but he couldn’t stop the rough chuckle that escaped. Henry and his wife—Marjorie—watched from the porch, hands twined together in a grip that spoke less of romance and more of comradeship.

As days turned into weeks, Reaper’s presence around their small, weathered house became as regular as the mail. He fixed the back fence that had been listing dangerously toward collapse, repaired the creaky hinge on the front gate, patched the crack in the driveway that kept snagging the wheelchair wheels.

Sometimes, when there were no more obvious fixes left, he just sat on the porch with Emma and her grandparents while she drew. The low rumble of his Harley parked at the curb, once a sound that made neighbors pull curtains aside warily, now blended into the familiar soundtrack of their street—kids shouting, dogs barking, TVs murmuring through thin walls.

Not everyone saw it that way.

“You really think this is wise?” asked Mrs. Salazar from next door one evening, leaning on the fence between their yards, arms crossed. She was a compact woman with sharp eyes and a sharper tongue, known in the neighborhood for both her homemade tamales and her unsolicited opinions.

Henry sighed. “Not you too, Rosa.”

She nodded toward Reaper, who was crouched beside Emma’s wheelchair adjusting the footrest. “You bring bikers around, cops follow. Cops follow, trouble comes. You don’t need more trouble.”

“We already got trouble,” Henry replied, voice tired. “Comes on paper, not on Harleys.”

“Exactly,” she said. “Paper people don’t look like that.” She jerked her chin at Reaper’s leather vest. “They don’t scare the kids.”

Emma looked up. “I’m a kid, and I’m not scared.”

“You’re also stubborn,” Mrs. Salazar said affectionately. “It’s a miracle you weren’t born a mule.”

Reaper straightened slowly, his knees protesting. He met Mrs. Salazar’s gaze with the weary patience of a man who had heard versions of this suspicion all his life.

“I don’t want trouble for them,” he said simply. It was more than he usually volunteered, especially to strangers.

“Then maybe don’t bring your club around,” she shot back. “They’re not exactly… subtle.”

“I haven’t,” he replied. “Not here.”

She narrowed her eyes, judging the truth of that. “Yet,” she added.

“Yet,” he agreed, not bothering to placate.

She sniffed, then looked at Emma, who was watching the exchange with the intensity she brought to everything. “You be careful, niña. The world already sees you as something fragile. Don’t make it easier for them to break you.”

“I’m not fragile,” Emma said. “I’m bendy.”

Reaper huffed a laugh. Mrs. Salazar shook her head but smiled despite herself. “Bendy is good,” she conceded. “Just… watch yourself.”

She went inside, screen door slamming behind her. Henry exhaled slowly.

“She’s not wrong,” he said quietly, watching Reaper.

“About me bringing trouble?” Reaper asked.

“About the world looking for easy excuses,” Henry replied. “You make an easy villain, son.”

“I know,” Reaper said. “I also know villains don’t build ramps.”

Henry studied him for a long moment. Then he nodded.

“No,” he agreed. “They don’t.”

If the story had ended there—with small acts of kindness and cautious acceptance—it would have been enough for some people. A nice, neat tale of redemption, packaged with coffee and pancakes and a wheelchair ramp.

But the world doesn’t like unlikely heroes. It prefers its monsters to stay monstrous and its saviors to look the way they do in movies.

When the state decided to intervene, they didn’t call it fear, or prejudice, or a system desperate to protect itself from lawsuits more than children.

They called it protocol.

It started with Ms. Brennan on the porch again, her clipboard like a shield, her mouth a thin, disapproving line. This time, she didn’t come alone. Two police officers flanked her, uniforms crisp, hands resting casually on their belts in a way that wasn’t casual at all.

“Mr. and Mrs. Hart,” she said, her tone falsely bright. “We need to discuss Emma’s placement.”

Emma sat just inside the open front door, half hidden behind the screen. Reaper was at the kitchen table, oil-stained hands wrapped around a mug of coffee Marjorie had insisted on making him before he left.

He stiffened at the sound of Ms. Brennan’s voice. Emma’s hand tightened on the wheel of her chair, fingers whitening.

“We discussed this last week,” Henry said, stepping onto the porch. “You said—”

“I said we were evaluating,” Brennan cut in. “And we have. I’m afraid the situation has escalated.”

“Escalated how?” Marjorie demanded, coming to stand beside her husband, flour dusting her apron.

Brennan gestured toward Reaper, who had moved into the doorway, his tall frame half blocking Emma from view. “By the presence of a known violent offender spending virtually all his free time around a vulnerable child.”

Reaper’s hands clenched. Known violent offender. The words were clinical, devoid of context, of the reasons behind the fights, the charges, the plea deals. They didn’t mention the times he’d stopped something worse from happening, only the times he’d been caught making it happen.

“I’m not ‘around’ her,” he said, his voice low but steady. “I’m here because they need help.”

“Your ‘help’ is exactly why we’re here,” Brennan said. Her eyes were shards of glass. “A man with your history has no business being near a young girl. We are removing Emma from this environment immediately pending an investigation into her grandparents’ fitness to protect her.”

“Removing—” Marjorie’s hand flew to her mouth. “You can’t—”

“You can’t just take her,” Henry snapped. “We’ve done everything you asked. We’ve gone to every meeting, filled out every form—”

“And yet you allow a member of a criminal motorcycle gang inside your home,” Brennan said coolly. “You allow him unsupervised access to Emma. That shows… poor judgment, at best.”

Reaper felt the old rage surge up his spine, hot and familiar. The urge to smash the clipboard from her hands, to shout, to intimidate, to do something, anything. But he could feel Emma behind him, small and shaking, and he knew—perhaps more clearly than he’d ever known anything—that if he lost control now, he would lose her forever.

“Reaper?” Emma’s voice was thin. “What’s happening?”

“It’s okay, kid,” he said without turning, his gaze locked on Brennan. “Stay back.”

“It is not okay,” Emma replied, rolling forward anyway. She bumped gently against the backs of his legs, then peered around him, her dark eyes blazing. “You said we were a ‘positive placement,’ Ms. Brennan. That’s what you wrote down last time. I read your notes.”

“You read—” Brennan blinked. “Those are confidential documents.”

“You left them on the kitchen table,” Emma shot back. “That’s bad social work.”

“This isn’t up for debate, Emma,” Brennan said, her patience thinning. “Sometimes adults have to make hard choices to keep children safe.”

“No,” Emma said, and Reaper heard in that single word all the stubbornness that had carried her through pain and loss and surgeries. “Sometimes adults make easy choices to keep themselves safe. There’s a difference.”

The officers shifted, uncomfortable. One, younger, cleared his throat. “Ma’am, maybe we can—”

“The order is signed,” Brennan said tightly. “We have full authority to remove Emma from this home today. If her grandparents wish to contest, they can do so through the appropriate channels.”

“The appropriate channels,” Henry repeated slowly, as if tasting the words. “You mean the ones that take months we don’t have, money we don’t have, and hope we can’t afford to lose.”

Brennan’s jaw tightened. For a second, something almost human flickered behind her eyes—regret, maybe, or the faint sting of knowing you’re doing something technically right and morally wrong. Then it was gone.

“Emma,” she said, softening her tone professionally. “Please gather your things.”

“No,” Emma said again, more quietly this time. Her hand shot out, gripping the railing of the ramp Reaper had built. “No. I’m not going.”

“Emma,” Marjorie whispered, tears spilling over now. “Honey, we—”

“Don’t say it’s for my own good,” Emma begged. “Please don’t say that.”

Brennan nodded to the officers. “We can do this the easy way or the hard way.”

The younger officer looked like he might be sick. The older one’s face settled into the impersonal mask of a man doing a job he didn’t want to think about too hard.

They stepped forward.

“No!” Emma shrieked as hands reached for her wheelchair. She grabbed the railing with both hands, knuckles white. “Reaper!”

Time slowed.

Reaper could see the scene in fragments, each detail painfully sharp. Marjorie crying, clutching Henry’s arm. Henry’s face red with fury and helplessness. Mrs. Salazar peeking through her curtains across the street, phone already in hand. Brennan’s clipboard held like a shield against her chest. The officers’ hands on Emma’s chair, prying her fingers loose one by one.

Every muscle in his body screamed at him to move.

He could cross the porch in two strides, he knew. Put himself between Emma and the car. He could knock the older cop aside, he was sure of it, the man’s center of gravity too high. He could tilt the young one’s wrist just so, disarming him of his baton before the kid even realized what was happening. He’d done it all before, in bar fights and club brawls and back alley beatdowns.

He could do it—and if he did, he would spend the rest of his life staring at Emma’s face through reinforced glass in a prison visitation room, if he saw her at all.

Her wheelchair jerked backward. She twisted, reaching out, fingers splayed, toward him.

“You promised!” she screamed. “You promised nobody rides alone!”

Reaper’s lungs seized. The words hit deeper than any punch.

He had said that, in an offhand moment at the diner when she’d asked him about the patch on his vest that read “No One Rides Alone.” He’d explained, haltingly, that it meant they took care of each other, that you didn’t leave your brother behind. She’d nodded and said, “Okay. Then I’m your little brother,” and he’d laughed, a real laugh, something rusty and startling.

And now she was being pulled away, wheels bumping down the ramp he’d built, her small hands clawing at the air toward him, and every fiber of his being howled at him to make it stop.

He didn’t move.

He stood rooted to the porch, fists clenched so hard his knuckles blanched, jaw locked. He heard Marjorie’s sob as the car door slammed. He heard Henry curse Brennan in words he hadn’t used in fifty years. He heard the engine start and the tires crunch on gravel.

He didn’t move.

The car pulled away, Emma’s face a pale oval in the rear window, her hand pressed desperately to the glass.

He stayed on the porch until the sound of the engine faded, his heart pounding like a drum against the inside of his ribs, his breath shallow. Only when the street fell silent did he bow his head.

It looked, to the neighbors watching, like the monster had been cowed. Like the system had reminded him of his place and he’d accepted it.

They were wrong.

They hadn’t destroyed the Reaper.

They’d woken him up.

That night, Reaper sat in the dim light of the clubhouse, his cut hanging heavily from his shoulders, the noise of the bar around him a dull roar. The Hells Angels Riverside chapter occupied a squat concrete building near the edge of town, its walls lined with photos and flags, the air thick with cigarette smoke and stories.

His brothers filled the room—men in various stages of age and ruin, their leather vests a uniform of shared history. Tank, with his bushy beard and booming laugh. Ghost, whose nickname came from his knack for appearing silently at a man’s shoulder. Cruz, younger but hard-eyed, silent as he nursed a beer.

They’d been talking about a run next month, about the rival club encroaching on territory, about a new mechanic who didn’t know what he was doing. The usual.

Reaper dropped his phone on the scarred wooden table. The screen still glowed with the text message Henry had sent hours earlier: “They took her. Group home on Oak Street. Please help.”

The words blurred slightly on the screen. Not from alcohol—he’d barely touched his drink—but from the adrenaline still coursing through his veins.

Tank noticed first. “You look like someone stole your bike,” he rumbled. “What’s up, Reap?”

Reaper stared at the table. His throat felt smaller than usual, as if the old injury had shrunk it another size. It took effort to force the words out.

“They took a kid,” he said.

Silence dropped over the table like a curtain. Cruz’s eyes sharpened. Ghost leaned forward.

“Define ‘they’ and ‘took,’” Ghost said quietly.

“Social services,” Reaper replied. “Social worker named Brennan. Called in the cops. Took her from her grandparents.”

“On what grounds?” asked Tank. For all his size and bluster, he was often the first to find the crack in a story.

“Me,” Reaper said. “My record. My ‘presence.’” His lip curled around the word. “Says a man like me has no business around a ‘vulnerable child.’ Says it makes them unfit to keep her.”

“Bullshit,” Cruz muttered.

Ghost tapped ash into the tray. “This the kid from the diner?”

Reaper nodded once.

“The one who draws you with angel wings,” Tank added, half teasing but mostly not.

Reaper grunted. “Yeah.”

“How old?” Ghost asked.

“Nine,” Reaper said. The number tasted wrong. Nine was too small for this kind of thing, for courtrooms and acronyms and phrases like “placement” and “fitness.”

Tank swore under his breath. “What’s the plan?”

Reaper looked up. Around the clubhouse, other conversations had quieted as the story spread in low murmurs. Eyes turned toward their table, toward him.

The version of him from a few years ago, the one drowning in grief and whiskey and fury, would have said something simple and immediate.

We break in. We take her back.

He imagined the scene—the roar of Harleys pulling up outside the group home, leather-clad men striding in, cops scrambling, headlines the next day about “Outlaw Bikers Storm Children’s Facility.” Emma, caught in the middle, traumatized and used as a cautionary tale on the evening news.

No.

No, the old him whispered.

The new part of him, the part that had watched a kid in a purple wheelchair fight to hold onto a railing, answered back: We’re not doing this the old way.

“We go to war,” Reaper said softly.

Cruz grinned, showing a gold tooth. “Now you’re speaking my language.”

“Not that kind of war,” Reaper added. “No fists. No guns. No threats we can’t deny later.” He scrubbed a hand over his face. “We go to war the way they do.”

“With paperwork?” Tank said, making a face.

“With pressure,” Reaper corrected. “With eyes. With people who know how to use the system instead of getting crushed by it.”

Ghost nodded slowly. “Lawyers.”

“Investigators,” Cruz added, catching on. “Journalists, if we have to.”

Tank shook his head in mock horror. “We’re trading in our bikes for briefcases now?”

“Bikes stay,” Reaper growled. “We’re not changing who we are. We’re changing how we fight.”

He picked up his phone again, scrolling through numbers he rarely used. Old favors owed, names he’d kept for emergencies—people who lived in the gray space between legal and criminal, who understood that sometimes justice and law were not the same thing.

He found one and hit call.

When the line connected, he spoke three words.

“We go to war.”

On the other end, a deep voice chuckled. “Finally,” it said. “I was getting bored.”

Within hours, the clubhouse took on a different energy. The pool table, usually the center of loud, rowdy games, was buried under stacks of paper. Laptops—some old, some questionably acquired—glowed atop the bar. Men who’d spent their lives navigating the underbelly of society now stared at spreadsheets and scanned PDFs.

They didn’t bring guns.

They brought a lawyer named Sinclair—a sharp, middle-aged woman with steel-gray hair and glasses perched halfway down her nose. She’d defended club members in the past on various charges, walking them through legal minefields with the weary competence of someone who’d seen too many men throw their lives away for pride.

“This is different,” she said when Reaper explained. “Custody court is a machine. It doesn’t care about your feelings. It barely cares about facts. It cares about procedure.”

“So we make procedure our friend,” he replied.

“She’s not your friend,” Sinclair said dryly. “But if you learn her language, she might not eat you alive.”

They brought a private investigator named Malik, quiet and methodical, who spent nights digging through public records and days talking to people who didn’t want to be seen talking to him.

He brought them records on Ms. Brennan—complaints that had been filed against her and quietly buried, cases where kids had been moved from barely adequate homes into truly dangerous ones because it made the paperwork neater. He brought them inspection reports on the Oak Street Group Home, some signed, some mysteriously missing. He brought them stories.

One parent whose child had come home with bruises and no explanation. A teenage girl who’d run away twice, claiming staff ignored her when older kids bullied her. A neighbor who’d seen kids out on the street at midnight, unattended, while staff smoked on the porch.

“None of this is a smoking gun,” Malik said, spreading printed emails across the table. “But it’s a pattern. Enough to raise questions.”

“Questions lead to investigations,” Sinclair added. “Investigations lead to judges getting nervous.”

“Nervous judges make safer decisions,” Reaper said.

“Sometimes,” she said. “If they think too many eyes are watching.”

So they made sure eyes were watching.

They didn’t threaten anyone. They didn’t need to. Twenty Harleys lined up outside a courthouse made their own kind of statement. So did a group of heavily tattooed men sitting quietly, respectfully, in the back row of a public hearing, arms crossed, eyes fixed on the proceedings.

When Henry and Marjorie went to file their petition to contest Emma’s removal, they didn’t go alone. Reaper walked beside them, silent but solid, and a rotating cast of brothers flanked them like an honor guard. Social workers stared. Clerks whispered. Ms. Brennan’s mouth tightened into a line so thin it looked like it might disappear.

“This isn’t intimidation,” Sinclair reminded them firmly. “You’re here as support. You smile. You hold doors. You don’t speak unless spoken to. You give them no ammunition.”

Reaper nodded. He could play by rules when the stakes demanded it. Especially now, when the stakes had a name and an age and charcoal-stained hands.

While the legal machine ground slowly into motion—petitions filed, hearings scheduled, home studies ordered—the war continued on other fronts.

The brotherhood started calling every parent they knew whose kids had passed through the Oak Street Group Home. They knocked on doors, spoke softly instead of loudly, listened to stories of lost belongings, missed medications, nights spent alone in rooms that smelled like disinfectant and fear.

A picture emerged, piece by piece. Nothing as dramatic as outright abuse—systems were too careful about covering those tracks—but a mosaic of neglect. Overcrowded rooms. Underpaid staff. Corners cut to save money. Kids treated as units in a system, not people.

“We can work with this,” Malik said, pinning photos and names to a corkboard like a detective in a TV show. “We get enough people to talk, we can push for a formal review.”

While they worked, Emma disappeared into the machinery.

Days turned into weeks. Reaper counted them like beads on a rosary. He’d never been religious, but he understood rituals, understood talismans. Every night, he sat at the diner in his corner booth, staring at the door, knowing she wouldn’t roll through it but unable to leave the habit behind.

Maggie refilled his coffee without comment. Lou the cook brought him meals he barely tasted. The regulars, who once gave him wide berth, now occasionally nodded, their eyes soft with something like sympathy.

One morning, as he sat alone at the booth, hands wrapped around his mug, Maggie slid a folded piece of paper onto the table.

“What’s this?” he asked.

“Came in the mail,” she said. “For you. No return address. Handwriting looks like a chicken stepped in ink, but…” She shrugged. “Thought you should see it.”

He unfolded it carefully. The paper was lined, torn from a notebook. The handwriting was indeed messy, but he recognized the loopy Es immediately.

Dear Reaper,

They won’t let me draw you.

They say I have to draw “appropriate subjects.”

I drew the ramp instead and said it was “architecture.”

They didn’t like that either.

The food is gross and the beds smell like bleach and crying.

My roommate snores and talks about running away.

My legs hurt more here than they did at home.

Ms. Brennan came and said you were “under investigation.”

I told her she was too.

She didn’t like that.

Dr. Abrams isn’t here.

They have a “counselor” who tells us to “be grateful.”

I told her gratitude is a feeling, not an order.

She didn’t like that either.

I like that you build things.

Please don’t break anything.

Don’t let them break you.

Nobody rides alone, right?

From, Emma

PS: Don’t be mad at Grandma and Grandpa. They’re trying.

A small, smudged drawing was taped to the bottom of the page. It was the diner, recognizable even in quick strokes. In the corner booth, a tiny figure with wild hair sat across from a larger one in a leather vest. Between them, on the table, was a coffee cup, whole and steaming.

Reaper traced the lines with one calloused finger. His vision blurred. He blinked hard.

“Damn kid,” he muttered, but the word lacked heat.

Maggie slid into the opposite side of the booth without asking. “She’s tough,” she said.

“Too tough,” he replied.

“World didn’t give her much choice,” Maggie said. “Same as you.”

He looked at her. “You were watching even back then, huh?”

“I watch everybody,” she said dryly. “It’s how I survive. I watched you walk in here for four years and not make a sound. I watched her roll in and crack you open like a walnut in ten minutes.”

He huffed a laugh. “That obvious?”

“To anyone who looks,” she said. “Unfortunately, Ms. Brennan only sees what she’s looking for.”

He folded the letter carefully and slid it into his pocket, close to his heart. “We’re not done,” he said.

“Good,” Maggie replied. “Because I’m not either.”

She nodded toward the other end of the diner where a small group of women sat, heads bent together. Teachers, nurses, secretaries. Mothers and grandmothers. They looked up in unison, meeting his gaze. There was steel there.

“People talk in here,” Maggie said. “They’re talking about Oak Street. About Emma. About you. Some of them are scared of your patches.” She shrugged. “Most of them love that you built a ramp.”

“It’s a start,” he said.

“It’s more than a start,” she corrected. “It’s a story. And people like stories, Reaper. Especially ones where the wrong guy turns out to be the right guy.”

He didn’t feel like any kind of guy just then. He felt like a coil wound too tight, like something waiting for a spark.

The spark came two weeks later.

It was a Tuesday night, late. The clubhouse was quieter than usual, the jukebox’s glow casting colorful shadows on the walls. Reaper sat at the bar, the taste of coffee long gone, replaced by the bitter tang of worry.

Malik burst through the door, breathless, his usual calm cracked.

“Fire,” he panted. “Oak Street. It’s on the scanner. Structure fire. Kids inside.”

Everything inside Reaper went white-hot.

He was moving before the words fully registered, grabbing his helmet from a hook, keys from his pocket. He barely heard Tank shouting, “Reap, wait!” or Ghost cursing as he scrambled after him.

The night air hit him like a slap. The Harley roared to life beneath him, the vibration grounding him just enough to aim the shock into motion. He peeled out of the lot, tires spitting gravel, engine screaming down the dark highway toward town.

Wind whipped past him, carrying the distant wail of sirens. The streets blurred—streetlights streaked into lines, houses flickered past like frames in a film. He leaned into turns, the bike an extension of his body, instinct taking over where thought failed.

As he crested the hill that overlooked Oak Street, he saw the glow.

It wasn’t the warm lamplight of a safe home. It was a pulsing, angry orange against the night sky. Flames clawed at the dark, smoke billowed thick and black. The Victorian-style house that had been repurposed into a group home was an inferno, the fire eating greedily at old wood and fresh paint.

He cut the engine and coasted the last few feet, swinging the bike sideways as he stopped. Tires squealed. The smell hit him—burning wood, melting plastic, something darker underneath.

On the lawn, a cluster of children huddled together, faces streaked with soot and tears. Two staff members shouted conflicting instructions. Ms. Brennan stood near the curb, cellphone pressed to her ear, eyes wide, hair disheveled. Panic made her movements jerky.

Reaper’s gaze swept the group, searching. Too tall. Too small. Wrong hair. Wrong chair.

“Where is she?” he roared, his voice tearing from his damaged throat louder than it had in years. He grabbed Brennan’s arm, spinning her to face him.

She yelped, dropping her phone. “What are you doing here? You can’t be—”

“Where is she?” he repeated, words razor-edged.

“I… I couldn’t get to the second floor,” Brennan stammered, eyes darting toward the burning house. “The stairs—there was smoke—”

“She’s in a wheelchair!” Reaper bellowed, every syllable fueled by terror. “You left a kid in a wheelchair on the second floor?”

“I tried—” Brennan’s voice broke. “I tried, but—”

He shoved her aside. The rest of her sentence lost in the roar of the fire.

Later, he would think he should have been scared. That any sane man would have paused, calculated odds, waited for firefighters whose gear and training made them better suited for this. But in that moment, there was no calculation, no odds. Only a singular, burning thought:

Not again.

He had already failed to pull one woman he loved from wreckage. He was not failing another.

He ran.

The front door was ajar, smoke pouring out in thick waves. Heat rolled over him, tangible as a wall. He took a breath through his shirt, pulled over his nose, and plunged in.

Inside, the world became a sick parody of itself. The familiar shapes of furniture warped and twisted in the flickering light. Smoke stung his eyes, turned the hallway into a tunnel of gray. The sound of the fire was a living thing, a crackle and roar that filled his ears.

He dropped to his knees instinctively, remembering advice he’d half listened to in some safety lecture years ago. Smoke rises. Air is clearer near the floor.

The air was only marginally less suffocating down there, but he could see a little more. He crawled, hand sweeping ahead, feeling for obstacles. Something soft brushed his fingers. He flinched, then realized it was a stuffed animal, singed at the edges. He pushed it aside.

The staircase loomed ahead, partially obscured by smoke. Flames licked the edges of the banister. The wood was already blackening, groaning under the strain.

He looked up. The second floor flickered between visibility and darkness. Somewhere above, he thought he heard a faint cough.

“Emma!” he shouted, but his voice was swallowed by the fire’s roar.

He started up the stairs, each step a negotiation. The heat was intense, like opening an oven door with your face too close but multiplied a hundred times. Sweat poured down his back, his clothes clinging, his leather vest hot enough to burn his skin beneath.

Halfway up, a step broke beneath his weight. He pitched forward, slamming into the banister. Wood splintered. Pain shot up his shin. He ignored it, grabbing the railing, hauling himself forward.

At the top of the stairs, the hallway was a corridor of smoke. Flames licked at the edges of bedroom doors. He coughed, lungs protesting. His eyes watered so badly he could barely see.

He moved by memory and instinct. Malik had shown them the floor plan during their research—where the girls’ rooms were, where staff slept, where emergency exits should be. He counted doors. One. Two. Third door on the right.

He kicked it open.

The room was a hellscape. Flames climbed the wallpaper, eating the edges of posters taped to the walls. The curtains by the window had already caught, fire curling up the fabric. On the floor, near the center of the room, Emma lay on her stomach, dragging herself forward with her arms, her useless legs trailing behind.

Her wheelchair sat near the doorway, knocked askew, one wheel already melting.

“Reaper?” she wheezed, voice barely audible over the roar.

He crossed the room in three strides, boots crunching over broken glass and debris. He scooped her up, her small body shockingly light in his arms. She clung to him instantly, arms wrapping around his neck.

“I knew you’d come,” she coughed into his shoulder.

He didn’t answer. Talking felt like a luxury he couldn’t afford. Smoke clawed at his throat. Every breath burned.

He turned toward the door—and stopped. The hallway beyond was a wall of flame now, the fire having found some new source of fuel. The staircase, he knew, would be gone. Even if it wasn’t, carrying Emma down it would be impossible.

There was only one other way.

He turned toward the window.

It was old, the frame warped, the glass already spiderwebbed with heat-induced cracks. Flame chewed at the curtains, but the window itself was still intact.

He shifted Emma in his arms, tucking her head into the crook of his neck, shielding her as much as possible.

“Hold on,” he rasped.

“To what?” she managed, attempting a weak joke.

“Me.”

He lifted one boot and kicked.

The glass shattered outward, exploding into the night. Fresh air rushed in, fanning the flames, pushing a wave of heat against his back. He squinted against the sudden brightness of the outside world—emergency lights approaching, figures on the lawn below, faces turned upward.

Fifteen feet, maybe a little more. Grass below, soft but not enough to make the landing safe. He calculated quickly—the angle, the impact, the way to twist so he took the brunt of it.

“Close your eyes,” he said.

“I can’t breathe,” she whispered.

“I know.” His voice cracked. “We’re going to fall now, okay?”

“Okay,” she said, because that’s what she did—she trusted him in the middle of hell.

He turned, cradling her against his chest, his back toward the open window. For a second, he balanced on the sill, the world outside a blur of sound and color.

He let go.

They fell.

The air rushed around them, cooler than the inferno they’d escaped but still thick with smoke. For a heartbeat, there was weightlessness, that sickening lurch of a roller coaster drop. Then gravity grabbed them, hard and unforgiving.

He twisted midair, years of bar fights and falls translating into a clumsy sort of grace. His body curved around Emma’s, arms tightening, trying to make himself a shield.

They hit the ground.

Pain detonated through him—sharp in his ribs, dull and crushing in his back, electric down his spine. The air whooshed from his lungs in one brutal exhale. For a second, the world went white, then dark, then slowly swam back into focus.

He was on his back, grass cool against his burned palms. Above him, the night sky stretched, stars faint against the orange glow of the burning house. His ears rang. His left side screamed with every breath.

Emma shifted against his chest, coughing. He felt the movement and sucked in a ragged breath of relief.

“You okay?” he croaked.

“I think so,” she rasped. “Everything hurts, but… in a normal way.”

Normal. He laughed then—a short, strangled bark that hurt like hell and felt like the only option.

Debris rained down around them—charred bits of wood, a fragment of a curtain. The house groaned ominously, the fire eating its structure from the inside out.

Voices shouted. Footsteps pounded. Someone yelled, “Over there!”

He tried to sit up. His body protested violently. Pain lanced through his side, sharp and bright. His vision swam.

Then they were there.

The brotherhood.

They’d come on the sound of his bike streaking away, on Malik’s shouted word “Fire!” on the instinct that when one of theirs left like that, something bad was happening.

Harleys lined the curb now, chrome catching firelight, engines ticking as they cooled. Men in leather vests formed a wall around him without needing to be asked, their bodies instinctively positioning between Reaper and the chaos.

To the firefighters running up with hoses and axes, the sight must have been unnerving—a phalanx of tattooed men, faces grim, surrounding two figures on the ground. To Reaper, flat on his back, it was the safest he’d felt in years.

“Move,” a paramedic snapped, pushing forward with a stretcher.

Tank stepped aside just enough to let them through, his bulk still a barrier between them and the crowd gathering on the sidewalk, phone cameras already raised. Ghost hovered at the edge, eyes tracking every movement, ready to intervene if necessary.

Emma clung to Reaper’s hand as the paramedics checked her over, their fingers gentle but efficient. They cut away part of her shirt to look for burns. They pressed stethoscopes to her chest, listened to her lungs wheeze.

“Smoke inhalation,” one said. “Possible bruising, but no obvious fractures. Let’s get her on oxygen.”

“No,” Emma choked, grabbing tighter onto Reaper. “Not without him.”

“I’m okay,” he lied.

“You are not okay,” the paramedic snapped. “You could have internal injuries. Broken ribs at least.”

“I’m fine,” he insisted, trying to sit again and failing. Pain spiked, white-hot, and he hissed through his teeth.

Emma’s eyes filled with tears. “Don’t be stupid,” she said hoarsely. “You always tell me to let people help. Let them help you.”

“Do as the kid says,” Tank rumbled. “For once in your life.”

The paramedics worked around his stubbornness, their professionalism unshaken by his protests. They cut his shirt away, revealing bruises already blooming across his chest and abdomen, dark flowers on pale skin. They palpated his ribs, earning a curse when they hit the broken one. They slid a brace under his neck, despite his grumbling.

“It’s a precaution,” the paramedic said. “Your spine took a hit. You’re lucky you can still move your legs.”

“Luck’s not something I believe in,” Reaper muttered.

“Then call it physics and good angles,” she replied. “Either way, you’re going to the hospital.”

Emma squeezed his hand. “You better,” she said. “I’m not going alone.”

He turned his head as far as the brace would allow, meeting her gaze. Her face was streaked with soot, tear tracks cutting pale paths through the grime. Her hair smelled like smoke and burnt fabric.

“I’m here, kid,” he said. “Nobody rides alone.”

He meant it more now than he ever had.

The aftermath rippled outward.

News traveled fast in small towns. Riverside woke up the next morning to headlines about the Oak Street Group Home fire, photos of smoke billowing into the sky, quotes from firefighters about outdated wiring and overloaded circuits. They mentioned the number of injuries—thankfully no deaths—and praised the bravery of “an unnamed local man” who had carried a child from the burning second floor.

The anonymity didn’t last long.

Witnesses talked. Kids who’d been on the lawn told anyone who would listen about “the biker” who’d run into the fire. Staff, embarrassed by their own inaction, grumbled about “reckless behavior” that could have made things worse. Ms. Brennan… well, Ms. Brennan found herself answering questions she’d never expected to face.

Why had she left a girl in a wheelchair on the second floor of a building with no accessible fire escape?

Why had previous fire code complaints been dismissed?

Why had she signed off on inspection reports that now appeared… incomplete?

The private investigator’s file on her and on Oak Street suddenly wasn’t just ammunition for a custody hearing. It was evidence in a much larger case.

The state launched an investigation. Then a second one, when reporters started poking around. Politicians who had quietly approved budget cuts to child welfare programs suddenly appeared on TV, promising “change” and “accountability.”

Sinclair, the lawyer, stood before microphones outside the courthouse, Reaper’s brothers forming a silent wall behind her.

“My client,” she said, gesturing toward Reaper—who stood in a clean shirt, arm in a sling, bruises peeking above the collar—“has been called a criminal, a thug, a danger to this community. Last night, when a fire broke out and children’s lives were at risk, he didn’t hesitate. He didn’t wait for permission. He went in. He did what every adult responsible for those children should have done. He risked his life to save a child he loves. That’s not the act of a monster. That’s the act of a person with a conscience and courage.”

Reporters shouted questions. “Is it true he’s a member of an outlaw motorcycle gang?” “What about his criminal record?” “Is this a stunt to influence the custody hearing?”

Sinclair’s gaze was cool. “My client’s past is a matter of record,” she said. “So is his present. So is the fact that, while he lay in a hospital bed with broken ribs and second-degree burns, certain officials were more concerned with spin than with the children they’re supposed to protect. Ask Ms. Brennan where she was when that fire started. Ask why Emma Hart was still on the second floor of a building with known safety issues.”

It was, as Maggie would later say, the verbal equivalent of pouring gasoline on smoldering coals. The story exploded.

Talk radio buzzed. Half the callers were outraged at a system that could leave a disabled child trapped in a burning building. The other half grumbled about “biker thugs getting turned into heroes.” Social media lit up with photos of Emma’s ramp, of Reaper’s bruised face, of Harleys lined up outside the hospital.

At the next custody hearing, the courtroom was packed. Not just with lawyers and social workers and the usual court staff, but with people from Riverside who’d taken the day off work, who’d found babysitters, who’d shown up because they’d heard a story that felt important.

Henry and Marjorie sat at the front, hands twined. Emma sat between them in her chair, face still a little pale but eyes clear. Reaper sat directly behind her, his sling replaced by a snug band of elastic around his ribs under his shirt, the patch on his vest visible.

Ms. Brennan, her hair pulled back so tightly it looked painful, sat at the opposite table with a lawyer from the state. Her eyes were ringed with exhaustion. She’d been suspended pending the outcome of the investigations. Rumors swirled. Some painted her as a villain, others as a scapegoat. The truth, as usual, was somewhere messier in between.

The judge, a middle-aged man with deep lines around his mouth, shuffled through a stack of papers on his desk. He’d once presided over one of Reaper’s assault cases, sentencing him to community service instead of jail after hearing the circumstances.

Now he looked from one side of the room to the other, then down at the petition in front of him.

“I have before me,” he began, “a petition from Henry and Marjorie Hart contesting the removal of their granddaughter Emma from their custody. I also have documentation regarding the recent fire at the Oak Street Group Home, ongoing investigations into that facility, and testimony from multiple parties about the events of that night.”

He adjusted his glasses, then lifted a separate document.

“I also have an unusual addendum,” he said dryly. “A statement of support for the Harts and for Emma’s continued placement with them, signed by… the Riverside chapter of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.”

A murmur rippled through the courtroom. The judge raised one hand.

“I will remind everyone this is a court of law, not a theater.” He turned to Sinclair. “Ms. Sinclair, care to explain this… addition?”

Sinclair rose, her suit immaculate. “Your Honor, my clients do not have considerable financial resources. They are on fixed incomes. They cannot offer Emma material wealth. What they can offer—and what they have shown consistently—is love, stability, and a support network.”

She gestured subtly toward the back of the courtroom where a handful of Reaper’s brothers sat in their vests, posture surprisingly respectful.

“The Hells Angels may not be a traditional support network,” she continued, ignoring the snorts from the state’s side, “but they are, undeniably, a family. They have pledged to assist with Emma’s care—financially, physically, and in terms of presence. They have already built modifications to the Harts’ home, provided transportation to medical appointments, and, in one particularly dramatic instance, risked life and limb to extract her from a burning building.”

The judge glanced at Reaper. “I am aware of Mr. Cole’s… actions during the fire,” he said. “I have read the report. I’ve also read his criminal record.”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Sinclair said. “Mr. Cole is not an angel, despite his club’s name. He has a history, as many people in this room do. The question before you today is not whether he has been perfect. It’s whether Emma is safer with people who have already demonstrated their willingness to walk through fire for her, literally, or in a system that left her on the second floor of a burning building.”

The judge looked at Emma. “Miss Hart,” he said, his tone softening. “Do you want to say anything?”

Emma straightened. Her hands gripped the wheels of her chair briefly, grounding herself.

“Yes, Your Honor,” she said. Her voice was clear, though a faint rasp remained from the smoke.

“You may,” he said.

“I know I’m a kid,” she began. “And I know kids don’t always get to decide things. But this is about me, so I think maybe I should get to decide some of it.”

A faint chuckle ran through the audience. The judge’s mouth twitched.

“Go on,” he said.

“When my mama died,” Emma said, “I thought… that was it. That all the good parts of life went with her. I was in a hospital a lot. My legs didn’t work right. People poked me and asked me questions and sometimes wrote things down without looking at my face.”

She glanced briefly at Ms. Brennan, then away.

“Grandma and Grandpa took me home,” she continued. “They made me pancakes when my stomach could handle it. Grandpa learned how to do my stretches so it wouldn’t hurt so much. Grandma sang really bad songs to make me laugh. They tried really hard even when their backs hurt and they were tired.”

She looked at Reaper then, and something in his chest cracked all over again.

“Then one day, I saw this man in the diner who looked like he was disappearing,” she said. “Not on the outside. On the outside, he looked like…” She gestured vaguely at his tattoos. “Like a statue made of knives. But inside, he looked like… like when you don’t water a plant and it starts to droop.”

A few chuckles again, quickly quieted.

“I thought maybe,” Emma said, “if I showed him he wasn’t invisible, he might remember he was alive. So I sat with him. And he got me hot chocolate and listened to my stories and didn’t talk very much but when he did, it was important.”

She took a breath. Her grandparents watched, tears in their eyes.

“I know what people say about him,” Emma said. “I listened at the vents and I read the notes Ms. Brennan left out. I know his file is heavy. I know he’s been in trouble. But I also know that when the house was on fire and nobody knew where I was, he came. He went into the fire. He got hurt and he still came.”

Her voice shook now, emotion cracking through the composure.

“He built my ramp,” she said. “He fixed our roof. He held my hand when they took blood and didn’t flinch when I squeezed too hard. He told me nobody rides alone, and he meant it. Please don’t make me ride alone.”

The courtroom was so quiet you could almost hear the judge’s heartbeat.

He cleared his throat, eyes suspiciously shiny. “Thank you, Miss Hart,” he said.

He turned to Ms. Brennan. “Ms. Brennan, do you have anything you wish to say before I rule?”

Brennan stood slowly. Her shoulders sagged, as if the weight of the last weeks had finally crushed the rigid posture she always maintained.

“Your Honor,” she began, “my job is to protect children. That has always been my job. Sometimes that means making hard decisions. Sometimes it means following protocols that… that don’t see the people behind the forms.”

She swallowed. “When I saw Mr. Cole with Emma, I saw risk. I saw his record, his affiliations, his… face.” Her mouth twitched. “I saw something that did not fit into the boxes on my checklist. I chose to see danger instead of… possibility.”

She looked at Reaper then, really looked, and her expression was complicated—regret, defensiveness, a grudging respect.

“I still believe,” she said carefully, “that the state has a duty to be cautious. But I also cannot ignore what happened at Oak Street. I signed off on reports I should have questioned more. I accepted assurances I should have scrutinized. That’s on me.”

She drew a shaky breath. “If the question is whether the Harts love Emma and are committed to her wellbeing, the answer is yes. If the question is whether Mr. Cole cares for her, the answer is… also yes. If the question is whether their home is… unconventional… the answer is absolutely yes.”

A ripple of laughter broke the tension.

“The world is not kind to children like Emma,” Brennan said. “They fall through cracks. If she has people willing to fight for her, I… I will not stand in the way of that.”

Her lawyer stared at her, stunned. The judge nodded slowly.

“Thank you, Ms. Brennan,” he said. “Your candor is noted.”

He shuffled his papers again, more for effect than necessity. He already knew what he was going to say.

“In considering the best interests of the child,” he began, “this court must weigh a number of factors: safety, stability, emotional bonds, the ability of the caregivers to meet her needs. The presence of Mr. Cole and his associates in the Harts’ lives introduces risks, yes. But it also introduces resources—financial, social, physical—that this court cannot ignore.”

He looked at Reaper. “Mr. Cole, you and I have met before. Not under pleasant circumstances. You stood before me then as a defendant with a chip on your shoulder and anger to burn. Today, you stand here as something else.”

“A dumbass with broken ribs?” Reaper muttered before he could stop himself.

A startled laugh escaped the judge. “Perhaps,” he allowed. “But also as someone who has chosen, despite his past, to put himself between a child and harm. That choice matters.”

He raised his gavel.

“It is the decision of this court that Emma Hart be returned to the custody of her grandparents, Henry and Marjorie Hart, with Mr. Cole recognized as an approved caregiver under their supervision. Child Protective Services will conduct regular check-ins, as is standard. The Oak Street Group Home is ordered closed pending the results of the ongoing investigations. Ms. Brennan is removed from this case effective immediately.”

The gavel came down with a sharp crack.

For a moment, no one moved.

Then, everything happened at once.