200 Parents Watched an 8-Year-Old Vanish on the School Steps—Only a Homeless 13-Year-Old Moved

I was invisible. That’s the first thing you need to know about me.

That’s the superpower poverty gives you when you’re thirteen years old and living in the passenger seat of a 2004 Honda Accord with 247,000 miles on the odometer.

You become a ghost.

You can stand on a street corner and people will look right through you like you’re a smudge on a windowpane.

They don’t see a boy; they see a problem.

A nuisance. A warning. A bad omen in a hoodie with frayed cuffs.

They see a reminder that their life is one missed paycheck away from mine, and that kind of reminder makes people angry.

So their eyes slide off you, and you learn to let it happen.

But the thing about being invisible is that you get to see everything.

And after a while, you start noticing things other people miss—because you’re not busy being seen.

My name is Theo.

I was thirteen, and I hadn’t been inside a classroom in one hundred and eighty-six days.

Instead, my education happened through the cracked windshield of our car, parked across the street from Riverside Elementary.

The glass was spiderwebbed on the passenger side from a rock kicked up on the freeway months ago, and every morning the sun caught those fractures and made them sparkle like fake diamonds.

My mother, Colleen, was asleep in the back seat.

She always slept there.

Her diner uniform was still on—black pants, a faded polo with ROSIE’S stitched over the heart, and the smell of coffee clinging to her like smoke.

Even in sleep her face looked tense, like she was bracing for someone to shake her awake and tell her we had to move.

She worked the graveyard shift at Rosie’s 24-hour diner, pouring coffee and scrubbing tables from 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m.

Not because she loved it, but because it paid cash tips and because night managers don’t ask too many questions if you show up on time and keep your head down.

She’d drive us here after work, to this spot, so I could watch the school while she caught four hours of fractured, restless sleep before we had to disappear again.

We didn’t have a driveway. We didn’t have a porch. We had “don’t park too long or the neighbors call it in.”

It was our routine.

It was my job.

Watch the school.

Watch the kids who had backpacks that didn’t have duct tape on the straps.

Watch the parents in their SUVs that smelled like new leather and vanilla air freshener.

Watch the life I used to have before the eviction notice, before the locks got changed, before the world decided we didn’t belong anymore.

I’d learned the rhythms of Riverside Elementary like other kids learned multiplication tables.

The exact minute the crossing guard stepped into the street. The exact angle of the afternoon sun when it hit the front steps. The sound of the dismissal bell—sharp and cheerful, like it didn’t know anything bad could happen after it rang.

It was Friday, November 15th, 2024.

The air had that damp November bite that crawls through fabric and settles in your bones.

My hoodie was thin, and there was a hole in the left elbow that the wind kept finding, nipping at my skin like something alive.

My sneakers were worse—the left sole had split again, and every time I shifted my weight it made that slap-slap-slap sound that felt like an announcement: *Look at him. Look at what he is.*

I’d tried to fix it with duct tape.

The pavement always wins.

I checked my watch out of habit.

It was a lie, of course.

The battery had died two months ago, but I still lifted my wrist like the motion itself could summon order.

In my head, I did the mental correction, adding the five minutes I knew it was behind.

3:52 p.m. Dismissal time.

I sat up straighter and wiped condensation from the inside of the window with my sleeve.

This was my show.

This was the only thing that gave my day structure—watching the doors open and the people spill out, predictable as clockwork.

I knew them all, not by name, but by pattern.

Mrs. Gable always came out first, phone already in her hand, tapping like her life depended on it.

The twin boys in red jackets always exploded out of the doors like they’d been launched, racing for the gate and colliding at least once.

The woman in the blue Lexus was always five minutes late and always looked like she was being chased by something invisible.

The man with the bald spot and the clipboard always stood by the curb like he was guarding the whole operation with sheer anxiety.

And then there was Ivy Reeves.

You couldn’t miss Ivy.

Eight years old, tiny, bright-eyed, hair like spun gold that caught whatever light existed and made it look warmer.

But it wasn’t her hair you noticed first.

It was the vest.

She wore an oversized leather vest that hung past her knees, swallowing her whole like armor borrowed from a giant.

Patches covered it—skulls, wings, little stitched symbols that looked half scary and half magical when you were a kid.

On the back, the rockers read: HELL’S ANGELS.

It should’ve looked ridiculous on someone her size, but somehow it didn’t.

It looked like a promise.

Like she believed that as long as she wore it, nothing bad could touch her.

She wore it every Friday.

She called it “Daddy’s Lucky Day.”

I’d seen her dad once, months ago, at pickup—big man, heavy boots, beard, tattoos disappearing into his sleeves.

He’d lifted Ivy like she weighed nothing, and she’d laughed like the world was safe because he existed in it.

That image stuck with me, probably because it was the opposite of my world.

No one lifted me like that anymore.

Ivy came skipping down the front steps, pink rain boots squeaking against the concrete.

Squeak, squeak, squeak—bright little noises in a gray afternoon.

She held an art project against her chest, something colorful with crayon wax gleaming in the dull light.

Even from across the street I could make out flames and a motorcycle shape, wild and proud and uneven the way kids draw things they love.

She paused at the bottom step like she was looking for someone.

Her chin tilted up, scanning the crowd of parents clustered near the curb.

And that’s when the van appeared.

I didn’t hear it first.

I felt it.

My stomach dropped with that sudden, sharp twist of instinct I’d learned to trust over the last seven months of living in the margins.

It was the same feeling I got when a cop cruiser slowed down beside our car at night, or when a stranger’s footsteps matched mine for too long.

Wrong.

Something’s wrong.

A white Dodge Ram, newer model, too clean for the neighborhood, moving slow like it had nowhere to be.

I clocked it instantly because I’d started collecting details the way other kids collected baseball cards.

License plates. Stickers. Dents. The way a door shuts.

My mom used to be a 911 dispatcher before everything fell apart, and when you grow up hearing voices on the phone say, *Please hurry,* you learn what matters.

“Details save lives,” she used to tell me, tapping her temple.

“Details, Theo.”

The van had Virginia plates.

7RX 4138.

A magnet was slapped onto the door: Enterprise Rent-A-Car.

But the fine print at the bottom said Fairfax, VA.

My brain snagged on that like a fishhook.

Why would a rental from Virginia be circling an elementary school in Sacramento?

The van circled the block once.

Just once.

Like a shark tasting the water.

Like someone checking angles and sightlines.

My breath shortened.

My palms went damp against my jeans.

I leaned forward, pressing my forehead close to the windshield, careful not to fog it up too much.

I could feel the cold glass against my skin, and somewhere behind me my mom shifted in her sleep and muttered something I couldn’t make out.

The van came back around.

Slower now.

It pulled up to the curb right in the fire lane—illegal, aggressive, like it didn’t care who saw.

Like it knew nobody would stop it.

The passenger window was dark, tinted enough that you couldn’t see a face.

The driver’s side was tinted too, but not perfectly—just enough to hide expression.

I could see a hand on the steering wheel.

Large. Pale.

The van idled, and the sound vibrated faintly through the air even from across the street.

Parents were everywhere—at least two hundred of them, a moving wall of coats and backpacks and car keys.

But nobody reacted to the van.

They never do.

Grown-ups trust the surface of things.

A clean vehicle. A confident stop. A person who acts like they belong.

They think danger always looks like danger.

They don’t understand that danger often looks like a normal afternoon.

Ivy stepped forward, still clutching her drawing.

Her boots squeaked again, closer to the curb now.

She looked toward the van, then away, like she was deciding whether it was her ride.

A small frown tugged at her face, and she hugged the art project tighter.

I could see the back of her vest shift as she breathed.

The HELL’S ANGELS patch rose and fell like a shield that didn’t know it was about to be tested.

My mind started firing in quick, ugly bursts.

License plate. Color. Make. Model. Location. Time.

7RX 4138. White Dodge. Fire lane. Ivy at the bottom step.

I wanted to shout, but shouting from inside a beat-up Honda with a sleeping mom and a torn sneaker makes you sound like what people already think you are: trouble.

And trouble is easy to ignore.

I looked at the crowd, searching for anyone paying attention.

A teacher in a yellow vest stood near the doors, smiling and waving like a mascot.

Parents were half-looking at their children, half-looking at their phones.

A dad laughed at something on a screen. A mom adjusted a scarf. Someone honked in the pickup line.

The van’s sliding door didn’t open yet.

It just sat there, waiting, like it knew the world would keep moving around it.

I swallowed hard, throat suddenly dry.

My eyes stung from not blinking.

The van’s brake lights flickered once.

A signal, maybe. A decision.

I lifted my hand without thinking, palm pressed to the inside of the glass.

As if that could stop anything.

Illegal. Aggressive. I….

Continue in C0mment 👇👇

pressed my face against the glass. “No,” I whispered. “Don’t stop.”

The driver’s side door opened. A man stepped out. He was massive, maybe 6’2”, built like a tank turret. Black leather jacket, military posture. But it was the ink that froze my blood. A snake tattoo, black and jagged, crawling up his neck, its head resting right at his jawline. He didn’t look like a parent. He didn’t look like a teacher. He looked like violence wrapped in skin.

Then the passenger door slid open. Another man. Shorter, bald, wearing a navy blue windbreaker zipped all the way up to his chin. He moved differently. He had a hitch in his step, a limp on his left leg, and when he reached for the door frame, I saw it—his right hand was missing a pinky finger.

Two men. One target.

I watched the snake-man scan the crowd. His eyes didn’t drift; they locked. They found Ivy Reeves like a laser guidance system. She had stopped skipping. She stood there on the sidewalk, clutching her crayon drawing, looking at this stranger who was blocking her path. I saw him smile, but it wasn’t a smile. It was a baring of teeth.

I rolled down my window, the cold air rushing in. I needed to hear. “Ivy Reeves,” the man said. His voice carried, low and smooth. “I don’t know you,” Ivy said. Her voice was high, trembling. She took a step back. Squeak. “Your daddy sent me to pick you up, sweetheart. There’s been an emergency.”

Liar. My brain screamed it. Liar, liar, liar. I knew Ivy’s routine. Her dad picked her up. Or “Uncle Bones.” Or one of the other bikers. Big men with loud bikes and gentle hands. Never a stranger in a rental van. “No,” Ivy said, louder this time. “Daddy picks me up.” She turned to run.

The man moved with terrifying speed. His hand, the size of a catcher’s mitt, clamped onto her upper arm. I saw the fabric of the leather vest bunch up. I saw Ivy flinch. “Daddy!” The scream cracked the air. It was a sound that should have stopped the world. It was raw, primal terror. Daddy!

Two hundred people were there. Two hundred parents, teachers, kids. I saw a soccer mom in a Suburban roll up her window, her eyes darting away. I saw Mrs. Herrera, the dismissal teacher, look up, frown, and then turn back to a student, dismissing it as a tantrum. I saw the world pause, look, and then decide it wasn’t their problem.

But it was my problem.

I threw the car door open. “Hey!” I screamed, my voice cracking, high and desperate. “Let her go! She doesn’t know you!”

I ran. My flapping sneaker sole smacked the asphalt—slap, slap, slap—a pathetic drumbeat to my charge. I wasn’t big. I wasn’t strong. But I was moving.

The bald man—Pinky-less—was already shoving Ivy into the sliding door. She was kicking, her little pink boots thumping against his chest, but he was too strong.

“Hey!” I yelled again, reaching the curb.

The Snake-man turned to me. He didn’t look scared. He looked annoyed. He reached into his jacket, and for a split second, I saw the dull glint of metal tucked into his waistband. He stared right at me. “Back off, trash,” he snarled.

He shoved the bald man into the van, jumped into the driver’s seat, and slammed the door. Tires screeched. Burnt rubber filled my nose. I stood there, panting, watching the white van weave through traffic and disappear around the corner.

Virginia. 7RX 4138. Snake tattoo. Missing pinky.

I turned to the school. The crowd was murmuring now, a low buzz of confusion. Did you see that? Who was that man? Probably a custody dispute. Not our business.

I sprinted up the stairs, pushing past a startled dad. I burst into the main office. It smelled like copier toner and lilies. Principal Vance was behind the counter, adjusting her glasses. She was a woman who wore her authority like armor, sharp and unyielding.

“Call the police!” I gasped, leaning over the counter. “They took her! They took Ivy!”

Principal Vance looked up slowly. Her eyes didn’t land on my face. They landed on my hoodie with the hole in the elbow. They landed on my dirty hands. They landed on the sheer poverty radiating off me.

“Excuse me?” she said, her voice dripping with ice. “You are not a student here.”

“A van!” I shouted, pointing to the door. “Two men. A white Dodge Ram. I have the plate! You have cameras outside. You have to pull the footage right now! We can see where they went!”

She stood up, smoothing her skirt. She didn’t reach for the phone. She reached for her radio. “I don’t know who you are,” she said, her lip curling in a distinct sneer, “but you are trespassing on school property. I’m calling security.”

“You don’t understand!” I begged, tears hot in my eyes. “It was Ivy Reeves! The little girl with the vest! They kidnapped her!”

“Security to the front office,” she said into the radio, staring me down. “We have a transient causing a disturbance.” She looked at me with pure disgust. “Get out before I have you arrested.”

I froze. I looked at the phone on her desk. I looked at the monitor showing the live feed of the empty steps. She could save Ivy. She could call 911 right now. But she wouldn’t. Because she couldn’t hear the message; she could only see the messenger.

I was invisible.

“Fine,” I whispered.

I turned and walked out. I didn’t run this time. I walked with purpose. My left shoe flapped, but I didn’t care. I walked past the murmuring parents. I walked past my mom sleeping in the car. I walked three miles, my head down, replaying the license plate over and over in my head like a mantra.

7RX 4138.

The Hell’s Angels clubhouse was in an industrial park near the river. It was a fortress—high fences, barbed wire, a black steel gate that looked like it could stop a tank. I walked right up to the intercom.

A camera buzzed. A voice, gravel and smoke, crackled through the speaker. “Get lost, kid.”

“I have a message for Bones,” I said. My voice was steady. “It’s about Ivy.”

Silence. Then, the heavy clank of the lock disengaging. The gate slid open just enough for me to slip through.

A man was waiting for me. He had a beard that reached his chest and arms like tree trunks. He wore the cut—the leather vest. “Talk,” he said.

“Two men,” I said. “White Dodge Ram. Virginia Plate 7RX 4138. Enterprise rental magnet on the door. One guy is huge, snake tattoo on the neck. The other guy is bald, limps, missing the pinky on his right hand.”

The biker stared at me. “What happened?”

“They took her,” I said. “From the school steps. 3:52 PM. The Principal wouldn’t call the cops. She said I was trash.”

The color drained from the biker’s face. He didn’t ask if I was lying. He didn’t look at my shoes. He pulled a radio from his belt. “Prez. Get out here. Now.”

Three minutes later, the courtyard was full. Ivy’s dad—the President, a man they called ‘Hammer’—knelt in front of me. He was terrifying, a giant of a man with scars mapping his history on his skin. But his eyes were red-rimmed.

“Say it again,” Hammer whispered. “The plate.”

“7RX 4138,” I said.

Hammer stood up. He didn’t scream. He didn’t throw things. He went deadly still. He looked at the men around him. “Find it.”

They didn’t call 911. They called contacts in the DMV. They called friends at rental agencies. They called brothers in Virginia, in Nevada, in Oregon.

It took time. The kidnappers were pros; they had switched plates two towns over. But they made a mistake. They stopped for gas in a town called Loomis, and the bald man used a credit card.

Forty-one hours. That’s how long I sat in the clubhouse, eating burgers the prospects brought me, waiting.

Then, the call came. An old farmhouse, ten miles off the highway, deep in the foothills.

“Mount up,” Hammer said.

It wasn’t a request. It was a force of nature.

Ninety-seven motorcycles fired up at once. The sound wasn’t noise; it was a physical wave of pressure that shook the windows of the clubhouse. It was the sound of a storm breaking.

They put me in the sidecar of a glide driven by the bearded man, ‘Bones.’ “You earned this ride, kid,” he shouted over the roar.

We didn’t stop for red lights. We didn’t stop for stop signs. We took up the entire highway, a river of chrome and leather and righteous fury.

When we hit the dirt road leading to the farmhouse, the kidnappers must have heard the thunder. I saw the curtains twitch in the window. I saw the front door open, and the Snake-man stepped out with a shotgun.

He raised it, but then he lowered it. His jaw dropped.

He expected a police cruiser. He expected a negotiator with a megaphone.

He didn’t expect ninety-seven Hell’s Angels filling his driveway, his yard, and the road behind him.

Hammer killed the engine. The silence that followed was heavier than the noise. He stepped off his bike. He walked toward the porch.

“You have something of mine,” Hammer said.

The Snake-man dropped the shotgun. He raised his hands. He looked at the ninety-seven men behind Hammer, and he knew. There were no Miranda rights here. There was no bail hearing.

The door creaked open. A small figure ran out.

“Daddy!”

Ivy flew off the porch. Hammer caught her, burying his face in her hair. He fell to his knees, sobbing, holding her so tight I thought she might break. But she didn’t break. She held onto his vest, onto the patches.

The other bikers moved in. They didn’t run. They just flowed over the porch like a black tide, engulfing the Snake-man and the bald man. I turned away then. I didn’t need to see what happened next. I knew the code.

Monday morning, the routine resumed. But it was different.

I was back in the car. My mom was asleep. The school bell rang.

Principal Vance was standing on the steps, clipboard in hand, looking important.

Then she heard it. A low rumble. Then a roar.

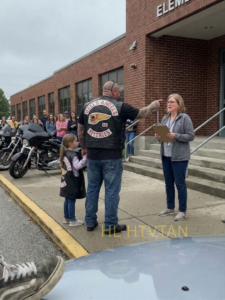

Ten bikes turned the corner. Then twenty. Then fifty.

The parents on the sidewalk froze. Principal Vance clutched her clipboard to her chest, her eyes widening.

The bikes pulled up to the curb, occupying the entire loading zone. Illegal. Aggressive. Beautiful.

Hammer got off his bike. He walked around to the back and helped Ivy down. She was wearing her vest. She was smiling.

Hammer took Ivy’s hand and walked her up the steps. The sea of parents parted. He stopped in front of Principal Vance.

She was trembling. “Sir, you can’t… the loading zone is for…”

Hammer leaned in. He pointed a finger at her chest. “You saw a dirty kid and you saw a problem,” he said, his voice low enough for only us to hear, but heavy enough to crush rock. “My boy Theo saw a crime and he saw a solution. You nearly got my daughter killed because you didn’t like his hoodie.”

He turned and pointed across the street. To the Honda Accord. To me.

Two hundred parents turned to look. Principal Vance turned to look.

“That boy,” Hammer said, “is under our protection. You see him? You treat him like he’s the Mayor. You understand me?”

Principal Vance nodded, pale as a sheet. “Yes,” she squeaked.

Hammer looked at me. He raised a fist in the air.

I raised my hand back.

I wasn’t a ghost anymore. I wasn’t invisible. I was Theo. And for the first time in a long time, the world saw me…

The first thing I noticed after Hammer raised his fist was the way the air changed.

It’s hard to explain if you’ve never been the kind of kid people look through. When you’re invisible, the world is a constant rush of motion that never touches you. Conversations skate past. Smiles belong to someone else. Fear belongs to you alone.

But when a man like Hammer points at you in front of two hundred parents and says, That boy is under our protection, the air thickens. It becomes aware.

I felt it—eyes landing on me instead of sliding away. Faces turning, mouths pausing mid-sentence. A woman clutching her purse tighter. A man with a coffee cup frozen halfway to his lips.

Principal Vance’s clipboard trembled like it suddenly weighed a hundred pounds.

She tried to smile. It came out like a grimace.

“I… I’m sorry,” she stammered, voice too bright, too fast. “We… we didn’t know.”

Hammer’s face didn’t soften.

“You didn’t know because you didn’t want to know,” he said calmly. “You didn’t even check the cameras.”

Principal Vance swallowed hard. “We had procedures,” she said weakly. “We… we were going to call—”

Hammer cut her off with a low, dangerous laugh. “Lady,” he said, “if I hadn’t found my kid, you’d be giving the same speech at a memorial.”

Silence fell so hard I could hear Ivy’s rain boots squeak against the concrete steps as she shifted beside her father.

Ivy looked at me across the crowd. She gave a small wave. Not dramatic—just a kid saying thank you in the simplest language she had.

My throat tightened.

Bones leaned down toward me where I stood near my mom’s Honda, still half in the shadow of the car. His beard smelled like smoke and engine oil. “You see that?” he murmured. “That’s the sound of your name becoming real.”

I didn’t know what to do with that. My hands felt awkward hanging at my sides. I tried to look calm, like I belonged, but inside I was shaking. Not from fear. From the shock of being seen.

Hammer turned back to the bikes. “Let’s go,” he said.

The Angels didn’t linger. That was another thing I didn’t expect. They weren’t there to intimidate for fun. They had done what they came to do: deliver Ivy and deliver a warning.

The engines fired again, the roar rolling down the street like thunder, and then they peeled away in a line of chrome and leather, leaving behind exhaust and a stunned community that suddenly couldn’t pretend it hadn’t failed.

As the last bike turned the corner, the parents slowly unfroze. They began whispering to each other, eyes darting between the school, the road, and me.

Principal Vance stood frozen on the steps for another moment, then turned sharply toward the office as if she needed to retreat into policy to breathe.

The bell rang.

Kids flowed inside like normal, backpacks bouncing, laughter returning cautiously. But the adults stayed on the sidewalk longer than usual, lingering like the scene had scratched something raw.

Across the street, my mom slept in the back seat with her diner uniform still on, mouth slightly open, exhausted. She hadn’t seen any of it. She never saw any of it. That was the cruel balance of our life: she fought to keep us alive while I fought to keep us from disappearing.

I slid back into the passenger seat and wiped the fog off the windshield with my sleeve. My hands were shaking again, but I kept them low so no one would notice.

Because even after being seen, you don’t immediately stop being a ghost.

You just start learning how to exist in daylight.

Two hours later, my mom woke up confused, blinking like the world had moved without her. “Theo?” she rasped.

I turned toward her. “Yeah.”

She rubbed her face. “Why are we still here?” she asked. “I thought we’d move after the bell.”

Normally we did. Loitering too long in one spot attracted attention. Attention attracted police. Police attracted questions. Questions attracted the kind of paperwork that swallowed poor people whole.

But today… I didn’t want to move.

“Mom,” I said quietly. “Something happened.”

Her eyes sharpened instantly. My mom didn’t have much left, but she still had instincts. She sat up, scanning the street. “What happened?” she demanded.

I swallowed. “Ivy Reeves,” I said.

She frowned. “The little girl with the vest?”

I nodded.

My mom’s face tightened. She’d noticed Ivy too, the way moms notice kids, even when they’re exhausted. “What about her?”

I told her.

I told her about the van, the plate, the snake tattoo, the missing pinky. I told her about Principal Vance calling me trash. I told her about the clubhouse, the ninety-seven bikes, the farmhouse, Ivy running out screaming “Daddy.”

By the time I finished, my mom’s face was wet.

She didn’t cry loudly. She didn’t have the energy. She just sat there with tears sliding down her cheeks like something in her finally broke.

“You ran at them?” she whispered.

I stared at my hands. “Yeah.”

My mom shook her head slowly, voice trembling. “Theo,” she whispered, “you could have been killed.”

I swallowed. “I know.”

My mom’s eyes burned with anger now—not at me, but at the world. “And those parents…” she whispered. “They watched?”

I nodded.

My mom’s jaw clenched. “Of course they did,” she murmured. “Of course they did.”

Then she looked at me with fierce, exhausted pride. “You did the right thing,” she said, voice cracking. “I’m proud of you.”

The words hit me harder than Hammer’s protection.

Because pride from your mother isn’t a warning or a promise or a threat.

It’s love without conditions.

I blinked fast. “I didn’t do it to be brave,” I whispered.

My mom smiled faintly through tears. “Nobody does,” she said. “They just do it because they can’t not.”

We sat there in silence for a while, watching the school like we always did, but it felt different now. The spot across the street didn’t feel like a hiding place anymore.

It felt like a location.

A coordinate.

A place that mattered.

Around noon, my mom’s phone buzzed. She checked it and froze.

“Work?” I asked.

She shook her head slowly. “No,” she whispered. “It’s… Riverside Elementary.”

My stomach tightened.

My mom hesitated, then answered. “Hello?”

A woman’s voice came through the speaker, clipped and professional. “Ms. Colleen… Reyes?”

My mom’s eyes widened slightly. She always flinched when people used her full name, like it meant trouble.

“Yes,” my mom replied cautiously.

“This is Principal Vance,” the voice said, and even through the phone I could hear that forced politeness—the tone of someone swallowing pride. “I’d like to speak with you and your son.”

My stomach dropped.

My mom looked at me. Her eyes asked the question she couldn’t say out loud: What now?

I leaned toward the phone. “I’m here,” I said.

There was a pause. Then Principal Vance said, “Theo… we need you to come to the school office.”

My mom’s voice sharpened instantly. “No,” she said. “Absolutely not.”

Principal Vance’s tone tightened. “It’s… not disciplinary,” she said quickly. “It’s regarding… yesterday’s incident.”

My mom’s jaw clenched. “Yesterday you called my son a transient,” she snapped. “Today you want him in your office? For what? So you can blame him for what you failed to stop?”

Another pause.

Principal Vance exhaled. “Please,” she said, and the word sounded unnatural coming from her. “There are… authorities here.”

My mom went still.

“Authorities?” she repeated.

“Yes,” Principal Vance said. “Detectives. They want to speak with Theo.”

My stomach turned cold. Detectives meant questions. Questions meant my mom’s car. Our address. Our lack of one. It meant the system noticing us, and when the system notices you, it doesn’t always help—it sometimes crushes.

My mom’s hand shook slightly on the phone. “Theo doesn’t have to—”

“I want to,” I said quietly.

My mom snapped her head toward me. “Theo,” she hissed.

“I want to,” I repeated, and my voice surprised me with its steadiness. “If they’re looking for Ivy’s kidnappers… I have information.”

My mom stared at me, torn. Fear and pride wrestling in her eyes.

I put my hand over hers on the phone. “Mom,” I whispered, “we already did the dangerous part.”

My mom swallowed hard, then said into the phone, “We’ll be there. But I’m coming with him.”

Principal Vance replied quickly, “Of course.”

We walked into Riverside Elementary like ghosts returning to a place we were never meant to enter. My sneakers still flapped. My hoodie still had the hole. My mom still wore her diner uniform, hair messy, eyes tired.

But this time, the front office looked different.

Not because the lilies smelled less sweet or the copier hummed quieter. Because there were two men standing near the reception desk in plain clothes, faces serious. One had a badge clipped to his belt. The other carried a folder thick enough to be a weapon.

They turned when we entered.

“Are you Theo?” the taller one asked.

I nodded, throat tight.

“I’m Detective Ramirez,” he said, and the name hit me like déjà vu because it sounded too official for my life. “This is Detective Sato.”

My mom squeezed my shoulder protectively. “He’s a minor,” she said quickly. “You talk to me too.”

Detective Ramirez nodded once. “Of course,” he said. “We just need a statement.”

Principal Vance stood behind the desk like a statue, face stiff, trying to look composed. But her eyes kept darting to me, then away, as if she couldn’t decide whether I was a threat or a problem to be managed.

Detective Sato opened the folder. “Theo,” he said calmly, “we have a report from multiple witnesses about a kidnapping attempt.”

“Attempt?” I blurted.

Sato nodded. “The girl was recovered,” he said. “Alive.”

My chest loosened so fast I almost sobbed.

My mom made a strangled sound. “Thank God,” she whispered.

Detective Ramirez’s gaze stayed steady. “But the suspects are still at large,” he said. “And your description may be critical.”

I swallowed, then started speaking—plate number, Virginia rental magnet, snake tattoo, missing pinky, limp. I described the men’s voices, their posture, the way the van circled once like a test. I described Ivy’s scream.

Detective Sato wrote quickly, eyes sharp.

When I finished, Ramirez nodded. “Good,” he said. “That’s solid detail.”

I stared at him. “Did you catch them?” I asked.

Ramirez hesitated. “We recovered Ivy,” he said. “The group who… intervened… brought us a location.”

I flinched. “The Angels,” I whispered.

Principal Vance’s face went pale again, as if the word itself made her want to faint.

Detective Sato’s lips tightened slightly. “Yes,” he said. “They provided information. We arrived shortly after. The suspects fled.”

My stomach dropped. “They got away?”

Ramirez’s jaw tightened. “Not for long,” he said. “Your plate number matches a rental. We have a lead.”

My mom squeezed my shoulder again. “So why are you here?” she demanded, voice sharp. “If you have the plate?”

Ramirez looked at her, then at me. “Because we need to know what happened at the school,” he said. “And why it took… outside intervention.”

Principal Vance stiffened. “We followed protocol,” she said quickly.

Detective Sato’s gaze snapped to her. “Protocol?” he repeated. “You didn’t call 911.”

Principal Vance’s face flushed. “It looked like… a custody dispute,” she stammered. “We didn’t want to escalate—”

Detective Ramirez cut her off, voice cold. “A child screaming ‘Daddy’ while being shoved into a van does not look like a custody dispute,” he said. “It looks like a kidnapping.”

Principal Vance swallowed hard. “I—”

Detective Sato looked at her desk. “Do you have cameras?” he asked.

“Yes,” she whispered.

“Did you pull footage?” he asked.

She hesitated. “We were… going to.”

Detective Ramirez’s tone sharpened. “When?” he demanded.

Principal Vance’s voice broke. “After—after security arrived.”

My mom let out a bitter laugh. “Security,” she spat. “For my son.”

Principal Vance flinched.

Detective Sato’s gaze turned harder. “Ma’am,” he said, “did you threaten to arrest this child for reporting a kidnapping?”

Principal Vance’s lips trembled. “He was… disruptive.”

Detective Ramirez’s eyes narrowed. “He may have saved that child’s life,” he said flatly.

The office went silent.

Principal Vance’s face twisted, humiliation and fear mixing. She glanced at me, and for the first time she really looked at me—not my hoodie, not my shoes, not my poverty—me.

“Why didn’t you call 911?” she whispered, almost to herself.

I stared back. “Because you didn’t see her as a child in danger,” I said quietly. “You saw me as a problem.”

Principal Vance’s eyes filled with tears. It looked like remorse. It also looked like fear of consequences.

Detective Ramirez spoke again, voice firm. “We’re taking the footage,” he said. “Now. And you will provide a full statement.”

Principal Vance nodded quickly. “Yes,” she whispered. “Of course.”

Detective Sato turned back to me. “Theo,” he said, softer, “where do you live?”

My stomach tightened.

I felt my mom stiffen beside me.

“We don’t have an address,” my mom said quickly, jaw tight. “We’re… between places.”

The detectives exchanged a glance.

There it was—the part of this story that could turn dangerous for us. Not because we did anything wrong, but because the system doesn’t know how to handle poverty without turning it into a case file.

Detective Ramirez’s voice stayed even. “Are you safe?” he asked my mom.

My mom’s eyes flashed. “We’re alive,” she snapped. “We’re not safe in the way you mean.”

Ramirez nodded slowly, like he understood more than he could say in that office. “Okay,” he said. “We have a victim advocate who can connect you with resources.”

My mom’s jaw tightened. “We don’t need charity,” she said.

Detective Sato spoke gently. “It’s not charity,” he said. “It’s support.”

My mom looked ready to argue, but I squeezed her hand. “Mom,” I whispered. “Please.”

She hesitated, then exhaled sharply. “Fine,” she muttered.

Principal Vance sat down slowly behind the desk, looking smaller than she had an hour ago. The plaque on the wall behind her—STUDENT SAFETY IS OUR PRIORITY—looked like a joke now.

Detective Ramirez handed me a card. “If you remember anything else, call,” he said. “Any detail.”

I took it carefully.

Then he did something that surprised me.

He looked me in the eye and said, “You did good.”

The words hit my chest like warmth.

Nobody in my life had said that without adding a “but” afterward.

I nodded once, too tight to speak.

As we left the office, Principal Vance stood abruptly. “Theo,” she called.

I stopped, turning slowly.

Her face was pale. “I… I’m sorry,” she said, voice strained. “For what I said. For—”

My mom’s hand tightened around mine.

I stared at the principal, feeling something strange.

Not forgiveness.

Power.

Because for once, she was the one trying to repair something, and I was the one deciding whether it mattered.

“You should be sorry for Ivy,” I said quietly. “Not for me.”

Principal Vance’s lips trembled. She nodded. “Yes,” she whispered. “Yes.”

Outside, the sky had cleared slightly. The November air still bit, but the sun was brighter.

My mom and I walked back to the car.

She sat in the driver’s seat for a long moment without starting the engine. Her hands trembled slightly on the steering wheel.

“I’m scared,” she admitted quietly.

I swallowed. “Me too,” I said.

My mom looked at me, eyes wet. “You brought the Angels into this,” she whispered. “You brought cops into this. Now people will look at us. Now—” she exhaled “—now they’ll know we’re living in the car.”

I stared at the school across the street. “They already knew,” I said softly. “They just pretended they didn’t.”

My mom’s throat tightened. “What if CPS—”

I flinched. The fear of the system taking me away from my mom was a constant shadow. Poverty makes you terrified not just of hunger but of being separated from the one person still trying.

I reached across and took her hand. “We’ll be careful,” I said. “But Mom—if we keep hiding, nothing changes.”

My mom swallowed hard. “You’re thirteen,” she whispered. “You shouldn’t have to think like this.”

I stared at her. “I know,” I said. “But I do.”

My mom closed her eyes briefly, then nodded. “Okay,” she whispered. “Okay. We do it your way.”

That afternoon, Sarah Chen—the social worker—met us at a community resource center. She was calm, sharp-eyed, and unlike Principal Vance, she looked at me like I was a person, not a stain.

She didn’t pity us. She didn’t lecture. She asked questions.

Where did we sleep? How often did we move? Did we have food? Was I attending school? Did my mom have identification? Did we have any relatives?

My mom answered cautiously at first, like any wrong sentence could trigger handcuffs or removal. But Sarah’s manner didn’t shift. She didn’t get impatient. She didn’t treat my mom like a bad parent for being poor.

She treated her like a woman drowning.

By the end of the meeting, Sarah had arranged something I didn’t think was real: a motel voucher for seven nights, a referral for transitional housing, food assistance, and an appointment for my mom to apply for a caseworker program that could help her find stable work that wasn’t destroying her body overnight.

My mom sat in the chair staring at the papers like they were counterfeit.

“Why are you helping us?” she whispered.

Sarah’s eyes softened. “Because your son did what adults failed to do,” she said simply. “And because you’re trying.”

My mom began to cry then—quiet, shaking sobs that made her shoulders collapse. I sat beside her, unsure what to do with seeing my mother’s armor crack.

Sarah handed her tissues and said gently, “It’s okay.”

On the drive to the motel, my mom kept glancing at me like she didn’t recognize her own child.

“You did all this,” she whispered.

I stared at the road. “No,” I said. “I just… said the truth to the right people.”

My mom shook her head slowly. “I don’t know how you became so brave,” she whispered.

I looked out the window at the passing streetlights. “I became invisible,” I said. “That’s how.”

The motel room smelled like old smoke and cheap cleaner, but it had a door that locked and a bed that didn’t have to be reclined. My mom stood in the middle of the room as if she didn’t trust it.

Then she sat on the bed and covered her face with her hands.

“It’s warm,” she whispered, voice breaking. “It’s warm.”

I sat beside her and felt a tightness in my chest I couldn’t name.

That night, for the first time in months, I slept without my shoes on.

Two days later, Riverside Elementary’s front steps looked different.

Not because the concrete changed. Because the adults did.

A uniformed officer stood near dismissal time. Not as a performance for cameras—because there were cameras now, pulled from the incident, replayed and archived. The district had ordered increased security. Parents stood closer to their kids. Teachers watched the curb with sharper eyes.

And Principal Vance… Principal Vance avoided looking at me.

But she couldn’t fully avoid it.

Because a story had already spread: the homeless boy in the car who noticed the plate, who tried to stop it, who went to the Angels.

Parents were talking.

Some were ashamed. Some were angry. Some were defensive. But none could pretend they didn’t know anymore.

On Wednesday, Ivy’s father—Hammer—returned to the school.

Not with ninety-seven bikes this time. Just three. Enough to be seen, not enough to be a riot.

He walked Ivy to the steps and held her hand longer than necessary, eyes scanning the crowd like he was still trying to believe she was safe.

I watched from across the street, near the resource center van where Sarah had arranged for us to meet again. My mom stood beside me now, hair brushed, wearing a clean sweater Sarah had given her from a donation closet. She still looked tired, but she looked less like someone ready to vanish.

Hammer spotted me immediately.

He walked across the street without hurry, like a man who expects the world to make room.

Parents watched, whispers rising. Some looked afraid. Some looked curious.

Hammer stopped in front of me.

He didn’t smile. He didn’t perform.

He crouched slightly so his eyes were level with mine.

“You got guts, kid,” he said quietly.

I swallowed. “I just… did what I could,” I whispered.

Hammer nodded. “That’s what guts is,” he said.

Then he reached into his vest pocket and pulled out a small patch—plain black with simple white stitching: a shield shape with a number on it.

“Prospect patch,” he said. “Not for the club. For you.”

I stared at it, confused.

Hammer’s eyes held mine. “It means,” he said, “if anyone messes with you, they answer to me.”

My mom made a small sound beside me—fear and disbelief.

I looked up at my mom, then back at Hammer. “I don’t want trouble,” I whispered.

Hammer nodded slowly. “You didn’t ask for it,” he said. “You just stepped into it. Now you don’t stand alone.”

He stood and looked at my mom. His voice softened—just a hair. “Ma’am,” he said, “your boy saved my little girl.”

My mom’s eyes filled instantly. “He’s… he’s just a kid,” she whispered.

Hammer’s face tightened. “Yeah,” he said. “And the world forgot that. But I didn’t.”

He turned back to me. “You keep your head straight,” he said. “You stay in school when you get back in. You don’t start thinking this patch makes you untouchable.”

I nodded quickly.

Hammer’s mouth twitched faintly. “Good,” he said. “Because it doesn’t. It just means you got a line behind you.”

He walked away.

The parents exhaled like they’d been holding their breath.

My mom stared at me, trembling. “Theo,” she whispered, “what is happening?”

I looked at the patch in my hand. It felt heavy, not with power but with responsibility.

“I think,” I said softly, “people are finally paying attention.”

And attention, once it starts, doesn’t stop where you want it to.

The following week, CPS came.

Not to take me away, not like my mom feared. A caseworker named Ms. Larkin sat with us in the motel room and asked careful questions. She explained the difference between neglect and hardship. She told my mom she wasn’t a bad mother for being poor, but they needed a plan.

We already had one.

Sarah Chen advocated for us. She presented my mom’s work history, the motel vouchers, the transitional housing application. She made it clear we weren’t refusing help; we were trying to climb.

Ms. Larkin looked at me and asked, “Do you feel safe with your mom?”

I looked at my mother, who had been breaking herself in diners to keep me fed, and said, “Yes.”

My mom cried quietly after that—relief and shame mixed together.

The caseworker left us with a timeline: enroll me in school within thirty days, secure stable housing within ninety, continued check-ins.

It wasn’t freedom. It was scrutiny.

But scrutiny is different when it comes with support instead of punishment.

We moved into transitional housing in December—two small rooms in a converted apartment building run by a nonprofit. It wasn’t pretty. The walls were thin. The neighbors were loud. But it had heat. It had locks. It had a mailbox with our name on it.

My mom stood in the doorway of our new place and whispered, “We have an address.”

I nodded, throat tight. “Yeah,” I said. “We do.”

When I walked back into a classroom in January, I felt like an alien.

Kids stared. Teachers smiled too brightly. Some whispered, “That’s the homeless kid.”

I wanted to disappear again.

But then I remembered Ivy’s pink boots. Her scream. The way adults had frozen. The way Hammer’s fist rose.

I forced myself to sit down.

The teacher—Mr. Powell—handed me a workbook and said quietly, “Welcome back, Theo.”

No pity.

No lecture.

Just welcome.

At recess, a kid tried to make a joke about my shoes.

I didn’t flinch.

I just looked at him and said, “Don’t.”

Something in my voice must have carried. He backed off. Not because I was bigger. Because I didn’t look like prey anymore.

Sometimes that’s all it takes.

The kidnappers were caught in February.

Not by the Angels. By police. Because the plate led to a rental agreement, which led to a credit card, which led to a motel, which led to a network.

It turned out Ivy hadn’t been a random target. Her vest hadn’t been cute—it had been a marker. The kidnappers thought a biker kid would be “easy” to snatch because they assumed her father lived outside the law and wouldn’t involve police.

They were wrong.

They also underestimated something else: a homeless boy’s attention.

When Detective Ramirez called to tell me they’d made arrests, his voice was surprisingly gentle.

“You did something important,” he said.

I swallowed. “Is Ivy okay?” I asked.

“She’s shaken,” he admitted. “But she’s alive.”

Alive.

That was enough.

Principal Vance resigned that spring.

Officially, it was “to pursue other opportunities.”

Unofficially, the district needed a scapegoat, and she was the easiest one. She’d become a symbol of institutional failure, and institutions love symbols because symbols absorb blame while the system stays intact.

But something did change.

Riverside implemented new dismissal protocols. Staff training. Real security.

And the PTA started a fund—quietly—called Theo’s Fund. They didn’t ask me. They didn’t ask permission. They just did it, awkwardly, like rich people trying to do something good without knowing how to talk about it.

The fund paid for school supplies for kids living in cars. It paid for vouchers. It paid for lunches.

My mom cried when she found out.

Not because of the money.

Because for once, the community acknowledged we existed.

Hammer’s club didn’t fade away either.

They didn’t hover. They didn’t stalk. But once a month, Bones would show up near the community center with a box of groceries “left over from a run,” and my mom would pretend it was coincidence and accept it with stiff gratitude.

One day, Hammer himself came to the nonprofit building and asked my mom if she needed anything.

My mom stood in the hallway clutching her cardigan like armor. “We’re okay,” she said quickly.

Hammer nodded. “Good,” he said. Then he looked down at me. “You staying straight?” he asked.

I nodded.

Hammer’s eyes softened just slightly. “Keep it that way,” he said. “You got a brain. Don’t waste it.”

When he walked away, my mom whispered, “He scares me.”

I whispered back, “He saved Ivy.”

My mom’s throat tightened. “So did you,” she said quietly.

And for the first time, I didn’t argue.

Because I was tired of minimizing my own courage just to stay invisible.

Somewhere between spring and summer, I started realizing something else:

Being seen wasn’t just about being protected.

It was about being accountable too.

When teachers now asked me to speak at assemblies about “safety,” I had to decide whether I wanted to be a symbol.

I didn’t.

But I did want kids to know this: if you see something wrong, you don’t wait for adults to be brave.

You do what you can with what you have.

Even if what you have is a flapping shoe and a broken watch.

On the last day of school, Ivy ran up to me on the playground.

She still wore the vest sometimes—smaller now, adjusted, less like a costume and more like a piece of her identity.

She held out a piece of paper. “I drew you,” she announced proudly.

The drawing showed a stick figure boy with a big cape and a car behind him, and a bunch of motorcycles in a line like a dragon.

In the corner, she’d written: Theo = hero

My throat tightened.

“I’m not a hero,” I said quickly.

Ivy frowned. “Yes you are,” she insisted. “Daddy says you are.”

I swallowed, then said the truth I could live with.

“I’m just… someone who didn’t look away,” I whispered.

Ivy smiled, satisfied. “That’s what heroes are,” she declared.

I looked up and saw my mom standing near the fence, watching us with a soft expression I hadn’t seen in a long time—hope.

And for a moment, in the bright summer light, I understood what the real roar of motorcycles had done.

It hadn’t just saved a girl.

It had cracked open a town’s denial.

And in that crack, my mother and I had found a way back into the world.

Not as ghosts.

As people.