617. Boston.

I stared at the screen like it might blink first.

I almost let it go to voicemail. I almost did the normal thing—assume spam, assume some stranger’s emergency wasn’t my emergency. But something in my gut—the same animal instinct that makes you sit up when a monitor alarms—made my thumb slide green.

“Dr. Catherine Weiss.”

Not Cat. Not Catherine. Not even a warm hello. Just my full name like a verdict.

The voice wasn’t kind. It was precise. Administrative. A voice that had said code blue and meant it. “This is Margaret Chen, Mass General. I’m the coordinator for Pediatric Neurovascular.”

My hand tightened around the Cheerios box until it creaked.

“We have a situation,” she said. “Eight-year-old boy. Rare vascular malformation in the posterior fossa. Dr. Carrian consulted. Dr. Yamamoto is on leave. The family is asking for you specifically.”

I swallowed. “What’s the patient’s name?”

There was a pause long enough for a distant intercom to page someone to the NICU.

Then she said, softly, like she already knew what it would do to me.

“Oliver Stratton.”

And just like that, a grocery store turned into a courtroom. A cereal aisle turned into a knife edge. And the man I’d spent years trying not to think about walked back into my life wearing a child’s heartbeat like a hostage.

—————————————————————————

I put the Cheerios back on the shelf like it had burned me.

I don’t remember the walk to the parking lot, but I remember the way the automatic doors breathed open and shut behind me, cold air on my face, the world going on like nothing had happened. A woman loaded cases of LaCroix into her trunk. A kid cried because his balloon had popped. Somewhere, a car horn yelled at another car horn. Everything was normal.

And my life wasn’t.

By the time I got home, the sun had dropped low and the apartment felt like a cave. I sat on my couch with my coat still on, my keys still in my hand, staring at the painting my mother had given me before she died—a lake at sunset, orange melting into purple, the kind of cheap art that shouldn’t matter and somehow did.

My phone buzzed again.

A text from Denise: Girl you will NOT believe what my boss just did. He ate my yogurt. MY yogurt. The blueberry one. I’m going to jail.

I didn’t answer. I just watched the screen dim, watched my reflection in it: the faint scar by my left temple, the almost-noticeable tug of asymmetry at the corner of my smile. The face I had learned to wear like armor.

Oliver Stratton.

Stratton.

My body remembered the name before my mind caught up. My shoulders went tight. My jaw locked. The old, sour anger rose like bile—hot and familiar and humiliating because it had never fully left.

I should probably back up.

Because if you’re going to understand why I didn’t immediately say yes—or no—you need to know what Richard Stratton did to me. Or what I believe he did. Or what I can’t prove but can’t shake.

You need to know the kind of man who could ruin your face with his hands and still sleep at night.

And you need to know the kind of woman you become when you survive it.

I was twenty-nine when I met Dr. Richard Stratton, and I met him the way so many women meet men who will later become a story they tell in warning tones.

He was a name first.

A legend. A keynote speaker. A whisper in hallways, a brag in résumés, a “you know who” at cocktail tables. The pioneer in facial reconstruction. The surgeon celebrities flew across oceans to see. The kind of doctor who didn’t just have patients—he had followers.

I was a second-year fellow at Johns Hopkins then, neurosurgery, bone-tired and hungry in a way that was less about food and more about being seen. I’d flown to Boston for a conference on minimally invasive techniques, and his keynote had been the kind of slick performance that made the audience forget they were supposed to ask hard questions.

But I asked one anyway.

During Q&A, I stood up and said, “Your published infection rate is exceptionally low given your sample size. Can you speak to your complication reporting criteria?”

You could feel the room shift. Like I’d slapped a chandelier.

He didn’t look annoyed. Not outwardly. He just blinked slowly, then smiled like a man indulging a child with a science project.

“Interesting,” he said. “Who are you?”

“Catherine Weiss. Neurosurgery. Hopkins.”

A murmur. Hopkins carried weight. Not enough to protect me, but enough to be noticed.

He answered the question with elegant non-answers. The room laughed in the right places. The moderator moved on. The show continued.

That night, at the hotel bar, I ordered a glass of white wine I didn’t want because I didn’t want to look like the only person not participating. The wine was sour. I kept pretending to sip it. I watched surgeons circle each other like sharks, their conference badges swinging like dog tags.

He sat down two seats away.

Ordered a scotch. Made a small ceremony out of it, like the world should pause to honor his palate.

“You’re the one who asked about complication rates,” he said without looking at me.

I froze.

“I’m curious,” I said. The truth was, I’d been nervous. My heart had hammered so hard I’d worried everyone could hear it.

He turned then. Really looked at me. And I know how this sounds—like a cliché, like I’m making excuses—but I felt something that made me sit a little straighter.

Not desire. Not attraction.

Recognition.

Like I’d stepped into a spotlight I hadn’t known was there.

“Walk me through your reasoning,” he said.

So I did. I cited studies. I pointed out discrepancies. I talked about sample bias and reporting thresholds. I spoke like a surgeon: calm, factual, sharp.

He listened without interrupting.

That alone should have warned me.

When I finished, he smiled.

“You’re smart,” he said. “What’s your name again?”

“Catherine.”

“Neuro,” he said, nodding like he’d already decided something about me. “I can tell by the way you think. Shame. You’d have made a good plastic surgeon. You’ve got the hands for it.”

His gaze dropped to my hands resting on the bar.

It wasn’t lewd. It was clinical.

And somehow that made it worse.

I should have gotten up then. I should have left. But he asked where I’d trained, and I told him about Chicago, and he told me he grew up in Naperville, and then suddenly we were talking about Midwest winters and lemon bars and the absurdity of paying twelve dollars for a conference sandwich.

He had a daughter studying art history at Columbia. He said it like a man listing trophies.

By the time I looked at my watch, it was past midnight.

“I should go,” I said.

“Already?” He sounded genuinely disappointed. “What time’s your flight?”

“Seven.”

He reached into his jacket and pulled out a business card. Not the cheap kind. Thick. Embossed. The kind that felt like money.

“If you ever need anything,” he said, sliding it toward me, “a consultation, whatever—call that number.”

I laughed, because it seemed absurd.

“Do I look like I need plastic surgery?”

He didn’t laugh back.

He looked at me with that same focused attention I used on scans.

“That mole on your left temple,” he said, “it’s asymmetrical. Probably benign, but you should have someone check it. And your septum is deviated. Not enough to cause breathing problems, but enough to throw off the symmetry of your face. Most people wouldn’t notice. But I noticed.”

The words landed in me like seeds.

I went up to my room and stood in the bathroom mirror for a long time, pulling my hair back, tilting my face, testing my smile. I’d never thought about my septum before. I’d never stared at my mole like it was a ticking clock.

I didn’t call him.

Not then.

Life had other plans.

My mother got sick that same year.

Pancreatic cancer—one of those diagnoses that doesn’t just rearrange your schedule, it rearranges your universe. By the time they found it, there wasn’t much to do besides watch a person you love become smaller inside their own skin.

She lasted six months.

I was with her at the end.

She kept asking if I’d remembered to water her plants, like that was the thing she couldn’t leave unfinished. African violets, stubborn little miracles. I kept saying yes, even though I hadn’t been to her house in weeks.

After she died, grief did what grief does: it found every vulnerable seam and pried it open.

I wasn’t just sad.

I felt ugly.

Not in a vanity way, not in a “poor me” way—more like I couldn’t recognize myself anymore. Like my face had become a stranger’s house and I didn’t know where anything was supposed to be. Richard Stratton’s comment about my septum grew roots in the dark. My mother’s death watered it.

I stopped seeing my face as mine.

I started seeing it as wrong.

Six months after the funeral, I found his card in a drawer.

I called.

His receptionist told me his waitlist was fourteen months.

I said fine.

Three days later she called back.

“Dr. Stratton reviewed your case personally,” she said. “He’s making an exception.”

A door opening.

I thought it meant I mattered.

I didn’t understand yet what it meant when a man like him decided you were worth bending rules for.

The first consultation was professional. That’s part of what made it so confusing later.

He examined my face, took photos, described options in the measured tone of someone discussing paint swatches.

“Mole removal is simple,” he said. “We can do it with minimal scarring. The septum is more complex. A minor rhinoplasty while we’re in there will improve symmetry. Might as well fix everything at once.”

I asked about recovery time. Risks. Outcomes. I did everything right.

I was a surgeon. I knew the questions. I knew consent forms and complication rates and the difference between arrogance and confidence.

But I also trusted him.

Because everyone did.

Because the world had told me he was a god.

Surgery was scheduled for a Friday in March.

My sister Margot flew in from Denver to take care of me, and she kept asking if I was sure.

“Cat,” she said, standing in my tiny kitchen while I pretended not to be nervous, “is this really what you want?”

“Yes,” I snapped, too quickly. “Stop worrying.”

The first week was normal: swelling, bruising, gauze, pain that throbbed like a slow drumbeat. I watched Netflix and let my brain turn off for the first time in months. I think I got through all of Breaking Bad. Margot made me soup and told me about her kids and acted like this was just another weird Catherine adventure.

Week two felt wrong.

The swelling wasn’t going down the way it should. There was numbness on the left side of my face, like my skin belonged to someone else. When I tried to smile, it tugged unevenly.

“Your smile looks different,” Margot said one night, sitting on the edge of my bed.

“It’s swelling,” I said.

She shook her head. “No. It’s not.”

She made me call his office. The nurse told me to give it more time.

So I did.

Time passed like that—me waiting, me hoping, me making excuses.

Three months later, I could finally see what happened.

The symmetry he’d promised to fix was gone.

My left side drooped slightly. Not dramatic, not grotesque—just enough that my face felt like a picture someone had hung crooked. The mole was gone, but there was a scar now, pink and raised and angry.

And my nose looked… the same. Maybe worse. Not improved. Not “enhanced.”

Just changed in a way that made my whole face feel off-balance.

I looked like a different person.

Not enough for strangers to gasp.

Enough for me to wake up and feel disoriented.

I drove back to his clinic and demanded to see him. I was shaking—not with fear, with rage. The kind that makes your vision sharpen.

He was colder this time.

“Healing varies by patient,” he said, barely glancing at me.

“I understood the risks of a competent procedure,” I said. “Not whatever this is.”

His jaw tightened.

“I’d be careful, Dr. Weiss,” he said softly. “Making accusations you can’t back up.”

“I can back them up. I’m a surgeon.”

His eyes flickered with something like amusement.

“Then you know how hard it is to prove,” he said.

He stood up.

“My assistant will see you out.”

I left his office with my fists clenched and my face burning.

And I told myself it was an unfortunate complication.

I told myself he wouldn’t do it on purpose.

But I’d be lying if I said that was the whole story.

Because the night before my surgery, he came to my hotel room.

It was around ten p.m. I was in bed with the pre-op instructions spread across the comforter like homework. I’d chosen a little boutique hotel near his clinic because it felt safer than staying with strangers, and I’d wanted to control every variable I could.

There was a knock.

I remember freezing with the paper in my hands.

I looked through the peephole.

Richard Stratton stood in the hallway wearing a suit, his tie loosened, his hair too perfect for the hour. He looked… informal. Which on him looked intimate.

I opened the door because my brain was still in doctor mode. Something’s wrong with the procedure, I thought.

“Can I come in?” he asked.

“It’s late,” I said. “Is something wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong,” he said, smiling. “I just thought tomorrow is a big day. You might be nervous.”

He stepped closer.

Too close.

“I’ve been thinking about you,” he said. “Since that night at the conference.”

I smelled scotch on his breath.

My stomach dropped.

“Dr. Stratton—Richard—” I stumbled over the name like it was a trap. “I appreciate you coming, but I should sleep.”

“Forget the procedure for one minute, Catherine.” His voice softened. “We had a connection. You felt it too.”

He reached out and touched my face, fingers cold against my cheek.

Every nerve in me screamed.

I stepped back. “I think you should go.”

For a split second, something dark moved across his expression—like a curtain pulled back.

Then the smile returned. Smooth. Practiced.

“Of course,” he said. “You’re right. I’m sorry. I’m overtired.”

He left.

And I stood there with my heart pounding, trying to decide if I should cancel surgery the next morning.

He’d had a few drinks. He’d misread the situation.

That didn’t mean he was a bad surgeon.

That’s what I told myself.

That’s what I needed to believe.

So I went through with it anyway.

And afterward, when my face changed, when he dismissed me, when the board review came back within standard of care, that memory of his hand on my cheek became a question I could never answer:

Was it an accident?

Or was it punishment?

I tried to file a complaint with the medical board. Do you know how hard it is to prove surgical misconduct when the notes are “meticulous” and the man has an army of influence?

They reviewed his records. Said everything appeared standard.

Case closed.

I consulted a malpractice attorney. She told me I had maybe a twenty percent chance of winning, and even if I did, it would take years.

“You’ll be known as the doctor who sued Richard Stratton,” she said. “Is that how you want to be known?”

I didn’t sue.

Instead, I worked.

I threw myself into training like it was the only thing that could save me.

And maybe it was.

I specialized in pediatric neurovascular cases—the hard ones, the ones that make other surgeons blanch. Tiny arteries. Deep brain structures. The kind of work where your hands must be calm even when your soul is screaming.

I got good.

Not just good.

I became one of the best.

One of maybe five surgeons in the country who could do what I do.

So when Margaret Chen said Oliver Stratton, I understood the truth underneath her calm voice:

This wasn’t just a medical case.

It was a reckoning.

Denise came over the night of the call like she always did when my silence got too quiet.

She showed up with Thai food and a bottle of wine and didn’t ask questions for the first half hour. That was her gift—she could sit in the dark with you without trying to turn on the lights.

We watched a home renovation show where a couple cried over a kitchen island like it had cured cancer.

Finally she looked at me and said, “You want to tell me why you look like you’ve seen a ghost?”

So I told her.

She didn’t interrupt. She didn’t gasp. She just listened, her face tightening at the right moments like she was taking notes for a trial.

When I finished, she said, “You can’t do it.”

“Denise—”

“No. Cat.” She leaned forward, elbows on her knees. “Think about what you’re saying. You hate this man. You think he deliberately disfigured you. And you want to cut open his child’s brain.”

“I never said I want to.”

“But you’re thinking about it.”

“A kid’s life is at stake.”

“There are other surgeons.”

“There aren’t,” I snapped. “Not really. Not for that location. Not with that vascular pattern. By the time they coordinate a transfer—”

She held up a hand. “Okay. So let’s pretend you do it. What happens if something goes wrong?”

Something cold settled in my stomach.

“This is his son,” she said. “If anything happens—anything—even if it’s not your fault, he’ll destroy you. He’ll say you did it on purpose. He’ll drag you through every board and every courtroom and every headline.”

“Or,” I said, voice thin, “I could save the boy’s life and none of that happens.”

Denise stared at me for a long moment, then lifted her wine and took a long drink.

“Sure,” she said. “Or that.”

She wasn’t being cruel. She was being honest.

And honesty can feel like cruelty when you’re desperate for permission.

The next morning I was in the OR by six for a scheduled case: nine-year-old Marisol with a tumor near her optic nerve. I focused the way I always did—laser narrow, hands steady, mind quiet.

Surgery is the one place my thoughts don’t chase me.

Afterward, when I peeled off my gloves and scrub cap and stepped into the hallway, my phone buzzed.

Unknown number.

Then a text.

Dr. Weiss, this is Richard Stratton. I need to speak with you, please.

I stared at the word please until it blurred.

I didn’t respond.

Over the next three days he called seven times. I didn’t answer. He left voicemails. I listened to one late at night, curled on my couch like a teenager with a broken heart instead of a thirty-something surgeon with an operating schedule.

“Catherine,” his voice said, smaller than I remembered. “I know what you must think of me, but Oliver—he’s everything. He’s all I have. Please.”

I deleted it.

Then I lay in bed and felt something I didn’t expect.

Not satisfaction.

Not triumph.

Something complicated, like an old bruise being pressed.

I called my sister.

Margot answered with chaos in the background—kids, cartoons, someone yelling about socks.

“You should say no,” she said immediately. “That man is a monster.”

“What about the boy?”

“The boy isn’t your responsibility.”

“He’s a child, Margot.”

She went quiet. I heard a small voice in the background—Lucas asking for a snack.

“Just a minute, honey,” she called, then returned to me softer. “Cat… you do this and you’re a saint. But if something happens—Dad’s health is bad enough without watching you get dragged through court.”

Dad.

I hadn’t even thought about Dad.

He was in a memory care facility in Ohio. I’d been meaning to visit for months. Meaning to had become a kind of prayer I never answered.

“How is he?” I asked.

“Same,” Margot said. “Worse, maybe. He asked about Mom again last week. Thought she was still alive.”

“Did you tell him?”

Silence.

“I have to go,” she said finally. “Lucas needs me.”

“Margot—”

She hung up.

I sat there staring at my phone, thinking about my father calling me by my mother’s name the last time I visited, holding my hand and telling me I looked beautiful like the day he married me.

I hadn’t called him back after that.

I kept meaning to.

I just didn’t.

Guilt is a strange thing—it doesn’t make you better. It just makes you heavier.

That weekend, I drove to Brooklyn.

I told myself I just needed to see it. Make it real. Separate the name from the ghost.

His house was exactly what I expected: colonial, red brick, manicured hedges like teeth. A basketball hoop in the driveway. A bicycle on its side near the garage like somebody had been interrupted mid-childhood.

I parked across the street.

Waited.

After twenty minutes the front door opened and a boy came out.

Dark hair. Skinny. Red Sox hoodie too big for his frame. He picked up the bicycle, looked at it like he was deciding whether to be mad at it, then dropped it and walked to the hoop.

He started shooting.

He wasn’t very good. Most shots clanged off the rim. But he kept going with a stubborn focus that made my throat tighten, because it looked like something I recognized.

The door opened again.

Richard Stratton stepped out.

He looked older than I remembered. Silver hair thinner. Weight around his middle. Sweatpants and a flannel shirt like he was trying on normal life and it didn’t fit.

He walked to the boy, put a hand on his shoulder, said something I couldn’t hear.

He took the basketball and shot.

He missed.

The boy laughed.

And for one moment, they looked like any father and son in America on a Sunday afternoon.

Not a monster and his victim.

Not a legend and a cautionary tale.

Just two people.

It shouldn’t have mattered, but it did.

Because it made the choice harder.

I drove home.

And Monday morning, I called Margaret Chen.

“I’ll do the consultation,” I said. “Only the consultation. I’m not committing to surgery yet.”

Margaret exhaled like she’d been holding her breath for days.

“Thank you, Dr. Weiss,” she said. “They’re expecting you tomorrow.”

Boston in winter is a different kind of cold.

It doesn’t just freeze your skin—it sharpens your thoughts.

I read a medical journal on the plane, some article about advances in intraoperative imaging, but the words wouldn’t stay in my head. My mind kept replaying the cereal aisle, the 617 number, Richard Stratton’s fingers on my cheek.

At Mass General, Margaret met me at the entrance with a visitor badge and a look that said she’d already read every headline that might exist in the future.

She led me through hallways that smelled like antiseptic and old coffee.

Richard was waiting outside the pediatric wing.

He stood when he saw me like I was a judge entering the courtroom.

He looked worse up close: dark circles, shaking hands, suit hanging wrong.

“Dr. Weiss,” he said. “Thank you for coming.”

I didn’t shake his hand.

“I’m here to see the patient,” I said. “Not you.”

He flinched, but he nodded.

Oliver was sitting up in bed playing a video game on his phone. Mario something. The room was decorated with a few brave attempts at cheer: a SpongeBob balloon, a stuffed dinosaur, a crayon drawing taped to the wall.

He looked small in the hospital bed, but his eyes were sharp.

He paused his game when I entered.

“Are you the doctor?” he asked.

“I’m one of them,” I said, pulling up a chair. “I’m Dr. Weiss.”

“My dad said you’re the best,” he said matter-of-factly.

I felt something twist in my chest.

“Did he?”

“He said you’re the only one who can help me.”

I leaned forward. “Can I tell you something, Oliver?”

He nodded solemnly like we were making a pact.

“I need to look at your scans before I can know if I can help. Sometimes the thing we think is wrong turns out different than expected. And sometimes… sometimes you can’t fix it at all.”

He considered that.

“Smart kid,” I said.

“Sometimes,” he agreed, and I almost smiled.

He hesitated, then said, “My dad really wants you to do the surgery. He said he talks about you a lot.”

My body went still.

“He does?”

“Yeah. He said he made a mistake once. He said he hurt you and he wishes he didn’t.”

The air in the room changed.

I forced my face to stay calm. Forced my voice to stay steady.

“He said that?”

Oliver nodded, fidgeting with the edge of his blanket. “What did he do?”

This child carrying his father’s guilt like a backpack too heavy for his shoulders.

“He and I had a disagreement a long time ago,” I said carefully. “But it doesn’t have anything to do with you. Your job is to get better.”

He watched me. “Okay.”

I stood. “I’m going to look at your pictures now, okay? The ones of your brain.”

He made a face. “Gross.”

I almost laughed then, the first real laugh in days.

“It is kind of gross,” I admitted. “But it helps me do my job.”

When I stepped out into the hallway, Richard was there like he’d been waiting to be sentenced.

“What did he say?” he asked, voice rough.

“He’s scared,” I said. “Like any kid would be.”

Richard swallowed. “Will you do it?”

“I haven’t seen the scans yet,” I said. “Don’t ask me that.”

His eyes flickered with frustration—then he caught himself, because he knew he couldn’t afford anger.

I walked past him without another word.

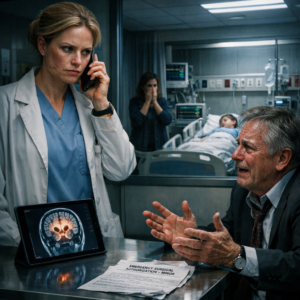

The scans were worse than I expected.

The AVM sat deep in the posterior fossa, wrapped around the brainstem like a fist. Fed by multiple arteries, draining into veins that looked like they were already straining under pressure. A tangle of vessels where millimeters meant life or death.

One wrong move and he’d bleed out on the table.

Risk of mortality: fifteen to twenty percent.

Risk of serious, permanent deficit: thirty percent.

Best-case success: fifty to fifty-five.

Those numbers would sound like a coin flip to most people.

To me, they sounded like a child on the edge of a cliff.

Without surgery, the cliff wasn’t a possibility.

It was a timetable.

I stared at the screen until my eyes burned.

Around eight p.m., Dr. Carrian found me in the reading room.

He was older than me by maybe ten years, calm in a way that only comes from having been through enough disasters to stop flinching.

“I’ve heard the stories,” he said, pulling up a chair. “About you and Stratton.”

I didn’t look at him. “Then you know why I’m here and why I shouldn’t be.”

“You have every reason to walk away,” he said.

“I know.”

“But you’re not going to,” he said, not a question.

I finally met his eyes.

He nodded toward the scans. “That boy’s got a time bomb in his head. And you’re the only one here who knows how to diffuse it.”

“Sometimes there are no good choices,” I murmured.

“Yeah,” he said. “Just choices.”

He stood. “Whatever you decide, make sure it’s a decision you can live with at three a.m.”

Then he left me alone with a screen full of blood vessels and a past that wouldn’t stay buried.

The next morning, I told Richard I would do the surgery.

We were in a conference room with bad coffee and fluorescent lights that made everyone look guilty.

Just the two of us.

He looked like he hadn’t slept in a week.

“Thank you,” he said, and his voice cracked.

“Don’t thank me yet,” I said. “There’s a significant chance your son will die on my table. A significant chance he survives and has severe deficits. Best case is only about fifty-fifty.”

“I understand,” he said.

“Do you?” I leaned forward. “Because if something goes wrong—if he dies, if he’s damaged—I will not accept you suggesting I did anything less than my best.”

His face flashed—offense, pride, something sharp.

“You think I’d do that?” he said.

“I think you’ve done worse,” I said, and the words tasted like iron.

Silence filled the room.

Then he said quietly, “Catherine… what happened between us?”

I laughed once, bitter. “You mean what happened to my face?”

He flinched.

“I was wrong,” he said. “I know that.”

“What exactly are you admitting to?” I asked.

He stared at his hands.

“I was attracted to you,” he said. “That night at your hotel. I’d been drinking. I thought we had something. I was wrong. You made that clear. And I should have done your surgery like a professional.”

“But you didn’t,” I said.

He swallowed. “No.”

“So you admit it,” I said, my voice low. “You deliberately—”

“I didn’t deliberately hurt you,” he said quickly, almost pleading. “I took an oath. I’ve taken that oath seriously my whole career.”

“Then why did my face change?” I demanded.

His shoulders slumped like a man finally letting go of a lie he’d been carrying.

“Because I was distracted,” he said. “Because I was angry at myself. I wasn’t focused. I made mistakes I wouldn’t have made if I’d been in my right mind.”

He looked up at me then, eyes raw.

“But I didn’t do it on purpose,” he said. “I need you to believe that.”

I sat back, my heart beating hard enough to hurt.

This man I had built into a monster.

This man who had harmed me, whether intentional or not.

“I don’t know if I believe you,” I said honestly.

“I know,” he whispered.

“I’m going to operate on your son anyway,” I said, “because he’s innocent. And I became a surgeon to help people, not to settle scores.”

His eyes filled with tears, and I hated myself for noticing, for feeling anything other than rage.

“The surgery’s Thursday,” I said, standing. “Get him ready.”

The night before surgery, I didn’t sleep.

At three a.m., I stood in the hotel bathroom and stared at my reflection.

The scar by my temple had faded, but it was there. The left corner of my mouth still pulled a fraction slower than the right. A stranger wouldn’t notice. I noticed every day.

For years, that asymmetry had felt like a theft.

Tonight it felt like a receipt.

Proof of something paid for.

I touched the scar gently.

And I thought, What if he was telling the truth? What if it was an accident?

Then I thought, Does it matter?

Because the child in that hospital bed didn’t ask to be born to Richard Stratton. He didn’t ask to inherit his father’s consequences like a disease.

At five a.m., I stopped trying to sleep.

At six, I scrubbed in.

The OR smelled like iodine and sterile drapes and the kind of fear no one says out loud. My team assembled: two residents, an anesthesiologist named Dr. Park, a scrub nurse named Maria with tiny hummingbird tattoos on her wrists.

Oliver was already under when I entered. So small on that table.

“Let’s begin,” I said.

And for the first time since the cereal aisle, my mind went quiet.

Because when a child’s life is on the line, the past becomes background noise.

And your hands become your truth.

The OR doors shut behind me with that soft, airtight whoosh that always feels like the world being sealed out.

Oliver lay on the table under the bright lights, his head pinned in a Mayfield clamp, his small shoulders disappearing under blue drapes. The anesthetic had smoothed his face into a kind of fragile peace. If you didn’t know better, you’d think he was just sleeping after a long day of being eight.

Dr. Park stood at the head of the bed, eyes on the monitors, hands resting lightly near the tubing like he could physically hold Oliver steady through willpower alone. Maria, the scrub nurse, laid instruments into my palm with a quiet rhythm, her hummingbird tattoos flashing each time she moved—two tiny birds frozen mid-flight, like even ink wanted to escape gravity in this room.

Two residents hovered on my right: Jalen Brooks, fourth-year, broad-shouldered and calm, the kind of guy you wanted next to you when things started bleeding; and Priya Nair, third-year, small and razor-sharp, eyes tracking everything I did like she was trying to memorize my hands.

“All right,” I said.

My voice sounded steadier than I felt.

“Time out,” Maria said, formal.

We went through the checklist: name, procedure, side, imaging, allergies, blood on standby. The ritual mattered. In surgery, rituals are how you tell chaos it has rules.

“Okay,” Dr. Park said. “He’s stable.”

I looked down at Oliver’s draped body and felt the weight of what I’d agreed to settle into my shoulders like a lead apron.

This wasn’t just a surgery.

It was a minefield built inside a child’s skull.

And somewhere in the waiting room, Richard Stratton was breathing in little shallow gulps like his lungs had forgotten how to be normal.

“Incision,” I said.

The scalpel slid through skin with the clean resistance of something living. A line of blood welled, then stopped as Maria dabbed, as cautery hummed, as the room narrowed into that familiar tunnel: light, hands, tissue, time.

Minutes became hours the way they always do—one decision at a time.

The posterior fossa is unforgiving. Space is tight. Structures are dense. The brainstem sits there like the root of a tree; everything passes through it. You don’t get to be clumsy down there. You don’t even get to be average.

I opened the skull with a small craniotomy, careful, deliberate, exposing bone like a pearl. Underneath, the dura pulsed softly—life reminding us it didn’t care about our plans.

When I opened the dura, the cerebellum appeared, pink-gray and delicate, and then the AVM came into view on the monitor as we guided the endoscope: a dense, angry tangle of vessels, too many of them, too close to where they had no business being.

A knot in the wrong place.

A storm waiting to happen.

“Good exposure,” Jalen murmured, like he didn’t want to jinx it.

I didn’t answer. My brain had already shifted into the only language that mattered now: anatomy and consequence.

“Micro,” I said.

Maria placed the microscope handles into my gloved fingers. The magnified view snapped into focus and the world became a landscape of blood vessels the size of threads, glistening under light. Tiny arteries feeding the malformation, veins draining it, everything under tension.

The plan was simple on paper:

Identify feeders. Clip or coagulate. Preserve normal vessels. Maintain perfusion. Reduce flow gradually. Remove nidus.

In reality, it was like disarming a bomb built by someone who hated you.

We worked millimeter by millimeter.

I traced each artery back, verified with Doppler, checked flow. Priya read off measurements, her voice steady, like numbers could anchor us.

“Feeder from PICA,” she said. “Likely branch A2.”

“Confirm,” I said.

Jalen angled the suction so I could see the vessel clearly.

Doppler hummed.

Positive.

“Clip ready,” I said.

Maria put the clip applier into my hand. I placed the clip gently—gentle like you’re not trying to dominate the tissue, you’re trying to persuade it.

When the clip closed, the vessel blanched slightly.

One feeder down.

Oliver’s vitals held.

Dr. Park’s voice floated from behind the drape. “BP stable. He’s tolerating.”

“Good,” I said.

Two hours in, the room settled into the rhythm that makes surgery feel almost peaceful—if you forget what’s at stake. Maria’s hands were flawless. The residents anticipated. Dr. Park adjusted fluids and pressure like he was tuning an instrument.

And then, around hour three, the first crisis hit.

It was subtle at first—just a small change in the color of the field. A vessel that looked slightly darker. A vein that seemed to swell.

“Hold,” I said.

My spine prickled.

The AVM shifted. Not physically, but in behavior. The hemodynamics changed the way they do when you’ve altered flow and the malformation starts rerouting like a desperate animal.

A tiny vessel tore.

Not a dramatic rupture. A pinhole.

But in the posterior fossa, pinholes can become waterfalls in a heartbeat.

Blood flooded the microscopic field, bright and sudden.

“Suction,” I snapped.

Jalen moved instantly. Priya’s breathing caught.

“Pressure dropping,” Dr. Park said, voice tightening. “He’s bleeding.”

“I know,” I said, and I forced my hands not to hurry. Hurrying is how you make it worse.

I packed gently with cottonoid, placed pressure exactly where the tear was. The bleeding slowed, but the AVM pulsed like it was angry.

“Bipolar,” I said.

Maria placed it into my hand. I cauterized with tiny controlled bursts—enough to seal, not enough to cook nearby structures. My own heartbeat thudded loud in my ears.

The vessel sealed.

The bleeding stopped.

Dr. Park exhaled. “Pressure recovering.”

I didn’t let myself breathe yet.

Because I’d learned something important in my career:

The first scare is never the last.

At hour five, my shoulders ached. My eyes felt dry behind the magnification. I took a half-step back and blinked, letting the world widen beyond the microscope.

My gaze flicked automatically to the clock on the wall.

11:42 a.m.

We’d started at 6:00.

Five hours in.

It felt like five minutes and five years at the same time.

“You okay?” Maria asked quietly, leaning in just enough that only I could hear.

Her voice was gentle, but her eyes were sharp. She’d seen a lot of surgeons break in small ways during long cases—hands trembling, voices snapping, judgment slipping.

“I’m fine,” I said.

She nodded like she didn’t believe me but accepted it anyway.

I re-centered. Put my hands back on the microscope.

And in that moment—ridiculous timing, cruel timing—my mind flashed to my own face in the mirror, swollen and bruised, Margot saying Your smile looks different.

My stomach tightened.

This child on the table wasn’t Richard Stratton’s son in the OR. Not to me.

He was just a kid whose life depended on my focus.

So I shoved the memory down.

“Okay,” I said. “We proceed.”

At hour seven, the second crisis hit.

This time it wasn’t bleeding.

It was swelling.

The brain tissue looked slightly tighter. The space narrowed. The brainstem region didn’t tolerate pressure; it never does.

“His ICP is creeping,” Dr. Park warned. “I’m seeing a trend.”

I stared into the microscope. The field looked… crowded. Subtle bulging.

“We’re going to give hypertonic,” Dr. Park said. “And mannitol.”

“Do it,” I said.

For a few minutes we worked in that tense, careful stillness, waiting to see if the swelling would respond.

It didn’t.

The cerebellum pressed forward, stealing working space.

“Cat—” Jalen started, then corrected himself. “Dr. Weiss. Should we pause?”

Pausing can save you. Pausing can kill you. In AVM surgery, you can’t always walk away midstream. You alter flow, the malformation becomes unstable. It can rupture while you’re being cautious. It can bleed when you’re not even touching it, just because you changed its environment.

I considered the options with the cold logic surgery demands.

“CSF drain,” I said.

Priya’s eyes widened. “External ventricular?”

“No,” I said. “We’re too deep. We’re going to do a controlled cisternal release.”

Jalen nodded. Priya swallowed.

We shifted approach, carefully opened the arachnoid planes, released cerebrospinal fluid in tiny measured amounts. The tissue softened slightly.

Not enough.

“Park,” I said without looking up. “I need him slightly lower. Controlled hypotension, but don’t tank him.”

“You got it,” Dr. Park said.

Oliver’s numbers dipped—carefully, safely, like stepping down a staircase.

The swelling eased.

The field opened again.

I felt the room exhale.

I didn’t.

Not yet.

At hour nine, the third crisis came in like a punch.

We were close. I could tell.

The nidus—the core tangle—looked smaller, less perfused. We had clipped and sealed feeder after feeder, working around the brainstem like we were defusing wires without knowing which color exploded.

And then the monitor changed.

Not the surgical monitor.

The heart monitor.

A sharp alarm. A sudden rhythm shift.

“Brady,” Dr. Park said immediately. “He’s dropping—thirties.”

My hands froze mid-motion.

Bradycardia in posterior fossa surgery can mean you’re irritating the brainstem. It can mean you’re killing him without seeing blood.

“Stop stimulation,” Dr. Park said. “Hands off.”

My instruments lifted away.

“Give atropine,” I said.

“Already,” Dr. Park said.

The seconds stretched.

Oliver’s heart rate hovered low, stubborn.

“Come on,” Maria whispered, not to me, not to anyone—just to the air.

Then the heart rate climbed slowly: 40… 52… 68…

Dr. Park’s shoulders loosened. “Back.”

I waited one more beat.

Then I leaned in again, hands steadier than they had any right to be.

Because this was the moment I’d feared the most:

The moment where your skill stops being enough and biology flips a coin.

I wasn’t going to lose this child because my past was in the room with me like a ghost.

I wasn’t going to.

At 5:17 p.m., after eleven hours that felt like an entire life, I placed the final clip and watched the last abnormal vessel lose its pulsing fury.

The AVM was quiet.

The field looked… normal.

Normal, in the miraculous way only surgeons understand: no sudden bleeding, no twitching alarms, no tissue turning the wrong color.

Dr. Park checked vitals. “He’s stable.”

Maria crossed herself, quick and private.

Priya’s eyes shone with relief she tried to hide behind professionalism.

Jalen let out a breath like he’d been holding it for hours.

I sat back a fraction, still staring into the microscope, letting reality catch up.

“It’s gone,” I said, voice low.

Oliver Stratton’s time bomb had been disarmed.

Not perfectly. Not without risk. But it was done.

We closed carefully—dura, bone, skin—returning his head to wholeness as best we could. When the final stitch tied, my hands finally started to tremble, not from fatigue but from the delayed release of fear.

I stepped away from the table and peeled off my gloves.

The OR lights still blazed like nothing had happened.

But everything had happened.

In the recovery unit, Oliver lay under warm blankets, ventilated, sedated. His eyelashes looked too long for his small face.

I stood at his bedside while the nurse checked pupils and reflexes.

“Does he move?” I asked.

“Not yet,” the nurse said. “It’s early.”

Of course it was early. Everything was early. His brain had been through war.

I watched the monitors, waiting for the first signs that he was coming back to himself.

Slowly, his fingers twitched.

Then his hand flexed.

A small movement, but it hit me like a wave.

“Oliver,” I said softly, though he couldn’t hear yet. “Come back.”

Minutes later, he began to wake.

His eyes fluttered open, unfocused. He made a small sound that was more complaint than pain.

“Hey,” I said, leaning in. “You’re okay.”

His gaze drifted toward me like his brain was swimming through fog to find a familiar shore.

“My head hurts,” he whispered.

“That’s normal,” I said. “You had big surgery.”

He swallowed, face scrunching slightly. “Did you fix it?”

“I did,” I said. “It’s gone.”

He blinked, then the faintest smile tugged his mouth.

It wasn’t perfectly symmetrical—because no one’s is when they’re half-awake after brain surgery—but it was a smile. A real one.

“Thanks, Dr. Weiss,” he murmured, and his eyes closed again.

Something in my chest loosened in a way I didn’t realize had been locked for years.

Richard was in the waiting room.

They always are.

Parents don’t leave. Even when the hospital forces them to. They hover like their presence might tether their child to life.

When I walked into the room, he stood so fast his chair scraped the floor.

His face was gray with fear.

He looked at my eyes like he could read the outcome in the way surgeons carry news in their bodies.

“How—” he started.

“He’s going to be okay,” I said.

The words landed like a miracle.

Richard’s face crumpled. A sound came out of him—half sob, half laugh, like his body didn’t know which emotion was safer.

He covered his mouth with his hand, eyes wet.

“Thank you,” he whispered.

I nodded once. I didn’t hug him. I didn’t soften.

But I did say something I hadn’t planned.

“You were right,” I said quietly.

He blinked at me.

“What you told Oliver,” I said. “About making a mistake. About hurting me. I’m glad you told him.”

His eyes spilled over.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m so sorry, Catherine.”

I held his gaze. Felt the old anger stir, but it wasn’t sharp the way it used to be. It was… tired.

“I know,” I said, and I turned and walked away before he could say anything else.

Because I’d given him enough.

Because I’d given his son everything I had.

And that was the line.

The next few days were a blur.

Oliver had a rough post-op course—because posterior fossa cases always do. He woke with some weakness on his left side and had trouble swallowing. His gait was unsteady. His speech was thick for a while, like his tongue didn’t want to cooperate.

Richard looked terrified every time a therapist walked in.

“This is expected,” I told him more than once. “We irritated delicate tissue. The brain needs time.”

Time was a concept Richard Stratton had never respected until it was his son’s brain demanding it.

On day three, Oliver cried because he couldn’t keep applesauce down.

“I hate this,” he said, tears leaking down the sides of his face.

“I know,” I said, sitting on the edge of his bed. “It’s unfair.”

He glared at me like he wanted me to fix it with a scalpel.

“Will I be normal?” he asked.

“Define normal,” I said.

He huffed. “Like… like before.”

I took a breath. Chose honesty, the only thing that actually helps.

“You might be different,” I said. “For a while. Maybe for longer. But different doesn’t mean bad. Different means your brain learned the hard way that you’re tough.”

He sniffed. “I don’t want to be tough.”

“I get that,” I said. “But you already are.”

A week later, he took his first steps down the hallway with a walker, therapist on one side, Richard on the other, gripping his hand like he was afraid Oliver would float away.

Oliver looked at me when he reached the end.

“Did I win?” he asked, panting.

I smiled, careful. “You did.”

“Can I get a prize?”

“Your prize,” I said, “is you get to go home.”

He groaned dramatically. “That’s not a prize.”

Richard laughed, a real laugh, and for a second he sounded like the man he might have been if he hadn’t spent his life worshipping himself.

Oliver went home two weeks later.

I went back to my life.

Or I tried to.

But something had shifted.

Not healed.

Shifted.

Like a bone that had been set after years of being crooked.

Three weeks after the surgery, a letter arrived at my apartment.

No return address.

Boston postmark.

My hands shook when I opened it, not because I was afraid of what it would say, but because I was afraid it would matter.

The handwriting was neat, deliberate—old-school, like the writer believed in permanence.

Dear Dr. Weiss,

He wrote that he’d thought about what to say and nothing felt adequate. He wrote that I saved his son’s life and he could never repay that. He wrote that he also destroyed something in me. He wrote that he didn’t expect forgiveness, but the guilt haunted him daily. He wrote that he’d stopped doing procedures three years ago because he couldn’t trust his own hands anymore.

And then he wrote the line that hit me hardest:

Oliver talks about you all the time. He calls you his hero. He asked me yesterday if he could be a surgeon when he grows up like you.

I read the letter three times.

Then I folded it carefully and put it in a drawer with Richard Stratton’s old business card.

Like my life was a museum of things I couldn’t throw away.

Denise called that night.

“Well?” she demanded. “Did he send you a fruit basket? A check? A kidney?”

“No,” I said. “A letter.”

“Read it.”

So I did.

When I finished, Denise was quiet.

“That’s… something,” she said finally.

“I don’t know what it is,” I admitted.

Denise sighed. “It’s him trying to control the narrative, Cat.”

“Maybe,” I said.

“Or he means it,” Denise said reluctantly, like the words tasted bad coming out of her mouth.

I stared at my bathroom mirror while we talked, tracing the scar on my temple with my fingertip.

“I saved a kid,” I said. “That’s the only part I’m sure about.”

“Then hold onto that,” Denise said. “Because men like him will try to turn your goodness into a trophy. Don’t let him.”

I didn’t know yet how right she was.

A month later, Mass General’s risk management department requested a meeting.

Hospitals don’t do anything without paperwork and fear. Saving a child’s life doesn’t protect you from bureaucracy. Sometimes it makes you more visible.

I sat in a conference room across from two administrators and a lawyer with careful eyes. Dr. Carrian sat beside me, arms crossed like he’d already decided he’d go down with this ship if it sank.

“We’re not here to accuse anyone of anything,” the lawyer said.

That’s what people say right before they accuse you of something.

“This was an unusually high-risk case,” one administrator said. “Given the patient’s family—”

“Given the father,” I corrected.

They hesitated. “Yes. Given Dr. Stratton’s profile, we’re anticipating media interest. We want to ensure documentation is… thorough.”

My jaw tightened.

“You’re worried he’ll come after me,” I said.

The lawyer gave a thin smile. “We’re prepared for all scenarios.”

I thought of Denise’s warning. If anything happens, he’ll destroy you.

Oliver was alive. Recovering. But even that didn’t guarantee safety. People sue when they’re happy. People sue when they’re guilty. People sue because they need someone else to carry their fear.

“I documented everything,” I said. “Intraoperative imaging, video, consult notes.”

“Good,” the administrator said.

“And,” the lawyer added, “we wanted to check in about your prior relationship with Dr. Stratton.”

My stomach dropped.

Dr. Carrian’s head snapped toward them. “That’s irrelevant.”

“It’s not irrelevant if there’s potential conflict,” the lawyer said smoothly.

I could have lied. I could have minimized it. I could have played the game.

But I was tired of games.

“He performed an elective procedure on me years ago,” I said. “I had complications. I believe his judgment was impaired. I filed a complaint. It went nowhere. I did not disclose it formally when I took this case because I was asked under emergent circumstances and the patient’s survival depended on my skill. I kept my work professional.”

The room went very still.

The administrator cleared his throat. “We’re going to need you to write a statement for the file.”

“I already wrote one,” I said. “The day I agreed. It’s in the chart.”

The lawyer’s eyebrows lifted, impressed despite himself.

“Of course you did,” he said.

Yes.

Of course I did.

Because if Richard Stratton had taught me anything, it was that paper can be a weapon.

When the meeting ended, Dr. Carrian walked me to the elevator.

“You didn’t have to tell them that much,” he said quietly.

“I’m not hiding,” I said.

He studied me. “That’s bravery.”

“No,” I said, pressing the elevator button. “That’s exhaustion.”

He smiled faintly. “Same thing sometimes.”

A few months later, I flew to Chicago for a medical conference.

It was the kind of event that used to thrill me—big rooms, bright screens, surgeons arguing like philosophers with scalpels. It was also the kind of event where men like Richard Stratton were worshipped.

But this time, I wasn’t a fellow sitting in the audience.

I was the one on stage.

My talk was on pediatric vascular malformations—posterior fossa AVMs, intraoperative strategies, emerging imaging. I spoke fast, sharp, the way I always do when I’m trying not to feel. The room listened in that particular hush surgeons get when they recognize someone speaking from the edge of experience.

Afterward, people lined up with questions.

A young resident asked about clip choice.

A senior attending argued about embolization timing.

Someone asked if I’d publish the case.

And then a woman approached who didn’t look like she belonged in that line.

Late fifties. Short gray hair. No conference badge.

She waited until the crowd thinned.

Then she stepped forward and said, “Dr. Weiss?”

“Yes,” I said cautiously.

She offered her hand. “Diane Stratton.”

My blood went cold.

“Richard’s ex-wife,” she added softly. “Oliver’s mother.”

I didn’t take her hand.

Not because she’d done anything, but because my body didn’t know the difference between Strattons.

“I heard what you did for my son,” she said. “I wanted to thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” I managed.

She looked at my face.

Not casually. Not rudely.

Clinically.

Her gaze landed on my temple scar. The faint asymmetry.

And her eyes sharpened with something like certainty.

“He hurt you,” she said quietly.

It wasn’t a question.

I didn’t answer.

That was answer enough.

“I thought so,” she said, nodding once like she’d confirmed a diagnosis.

My throat tightened. “Why are you telling me this?”

She exhaled. “Because what you did for Oliver—that was for Oliver. Not for Richard. Don’t let him turn your kindness into something he can use.”

My skin prickled.

“He will try,” she said. “He always does. Even when he’s sorry, it’s still about him.”

The words hit me like a slap because part of me already believed them.

“I know who I did it for,” I said, voice steadier now.

“Good,” Diane said. “Keep it that way.”

She hesitated, then added, “I was married to him for fifteen years. The charm? It’s a performance. The remorse? Sometimes real. Sometimes… strategic. He hurts everyone eventually. It took me too long to leave.”

“Why did you leave?” I asked before I could stop myself.

Diane’s mouth tightened. “Because one day I realized my life had become a room where I was always trying not to upset him. And I didn’t want my kids to think that was love.”

“Oliver lives with him,” I said, surprised.

“For now,” she said. “After his diagnosis, Richard fought hard to keep him. He used every connection. Every lawyer. Every sob story.” Her eyes flashed. “He loves Oliver, I’ll give him that. But love doesn’t excuse everything.”

I swallowed. “Did he ever… come to your hotel room? The night before a procedure?”

Diane’s face went still.

Then she said, “He did worse than that.”

A chill went through me.

She stepped closer, lowering her voice. “If you ever doubt your instincts about him—don’t. Your kindness is your strength, Catherine. But it’s also a doorway people like him will walk through if you leave it open.”

I stared at her, heart pounding.

“Why are you telling me this now?” I whispered.

“Because I owe you,” she said simply. “Not because you saved my son—though you did. Because I know what it’s like to be damaged by a man who smiles while he does it. And I don’t want you to carry this alone.”

Then she turned and walked away like she’d just dropped a bomb and trusted me to survive it.

That night in my hotel room in Chicago, I couldn’t sleep.

The city lights spilled through the curtains. Sirens wailed somewhere distant like the soundtrack of every American night.

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror and looked at my face.

The scar.

The asymmetry.

The proof.

And for the first time, I asked myself a question I’d avoided for years:

If it wasn’t on purpose… why hadn’t he tried to fix it?

If it was an accident… why had he turned cold?

If he was remorseful… why had he threatened me in his office?

I sat on the edge of the tub and cried quietly into a hotel towel like I was nineteen again instead of a surgeon who held children’s brains in her hands.

Grief isn’t logical. It doesn’t care about your credentials.

It just shows up when it’s ready.

When I got home, I did something I hadn’t done since my mother died.

I visited my father.

I don’t know why that was the thing that cracked open after everything else, but it was. Diane’s warning, Oliver’s recovery, Richard’s letter—it all stirred up the part of me that understood time doesn’t wait for you to be ready.

The memory care facility in Ohio smelled like lemon cleanser and overcooked vegetables. The halls were too bright. The TV in the common room was always too loud.

Dad was sitting in a recliner by the window when I walked in, hands resting on his knees like he was waiting for instructions.

He looked up slowly.

For a moment his eyes were blank.

Then something lit.

“Rose?” he said.

My mother’s name.

My chest tightened. I forced a smile.

“No,” I said softly, kneeling beside him. “It’s Catherine.”

He blinked hard like the name was a code he had to translate.

“Cathy,” he said finally, and his voice warmed. “Cathy-girl.”

He hadn’t called me that since I was small.

I took his hand. His skin was thin, papery. The veins stood out like map lines.

“Hi, Dad,” I whispered.

He stared at my face, and my stomach clenched because I didn’t know what he’d see.

“Pretty,” he said suddenly, like it was the simplest truth.

I laughed through a sting of tears. “Still?”

He nodded solemnly. “Always pretty.”

I swallowed. “Dad… do you remember Mom?”

His expression shifted, confusion sliding in.

“Your mother,” he said. “She—she’s at the store.”

“No,” I said gently. “Mom died. Remember?”

His face crumpled like I’d slapped him.

Then, just as quickly, the sadness vanished, replaced by a stubborn denial.

“No,” he said. “No, no. She’ll be back. She always comes back.”

I stared at him, grief rising sharp. Margot’s words echoed: Did you tell him?

I realized then it wasn’t about telling him. It was about loving him where he was, even when where he was broke your heart.

“I’m here,” I said instead. “I’m here.”

He squeezed my hand surprisingly hard.

“Good girl,” he murmured.

And in that moment, something in me softened—not about Richard, not about the past, but about myself. About all the ways I’d punished myself for not being able to control outcomes, not being able to fix everything.

My father’s mind was an AVM I couldn’t clip.

My mother was gone.

My face was changed.

But I was still here.

And I could still choose what kind of person to be.

A year passed.

Oliver recovered better than anyone had dared hope.

His swallowing returned. His gait steadied. The weakness faded. He had some residual coordination issues—fine motor tasks took longer, frustration came faster—but he adapted the way kids do, like their bodies understand survival in a purer way than adults.

Richard sent one more letter that year—shorter, quieter. No grand apologies. Just an update on Oliver, a photo of him grinning with a missing tooth.

I didn’t respond.

Not because I wanted to punish him.

Because responding would make it about him again.

And Diane’s warning stayed in my head like a compass needle:

Don’t let him use your kindness.

Denise, of course, had opinions.

“You’re not writing back?” she asked, incredulous, as we ate tacos on my couch one night.

“No.”

“Okay, but—just hear me out—what if he dies of guilt and then haunts you?” Denise waved a taco like it was a legal brief. “Then you’ll have TWO ghosts.”

I snorted. “If he dies and haunts me, I’ll ask him to pay rent.”

Denise laughed, then sobered. “Do you ever wonder if he did it on purpose?”

I stared at my plate.

“Every day,” I admitted.

Denise nodded slowly. “And?”

“And it doesn’t change what I did for Oliver,” I said. “It doesn’t change who I am.”

“Look at you,” Denise said, pointing at me like she was proud and annoyed. “Being emotionally mature. Disgusting.”

I smiled, and it tugged unevenly the way it always did.

And for the first time in a long time, it didn’t feel like a wound.

It felt like… evidence.

Three years later, I saw Oliver’s name in a pediatric journal.

Not a surgical journal.

A pediatric journal.

He was listed as a co-author on a paper about childhood migraine misdiagnosis and rare vascular anomalies—an article arguing for earlier imaging in kids with persistent headaches.

I stared at the screen for a long time.

Then I printed it.

Not to frame it.

Not to show off.

Just to hold it, like holding proof that something terrible had turned into something useful.

Margot called around that time, voice tired.

“How’s Dad?” I asked.

“Same,” she said. “He asked about Mom yesterday again. I told him she was in the garden. He smiled. Then he forgot.”

Silence.

Then Margot said, “Do you ever think about that boy?”

“Oliver?” I said.

“Yes.”

“Sometimes,” I said carefully.

“Was it worth it?” she asked.

I thought about the OR. The blood. The alarms. Richard’s shaking hands. Oliver’s grin with the missing tooth. Diane’s warning. The journal article.

“I saved a kid’s life,” I said. “That has to count.”

“But do you feel better about what Richard did?” Margot asked.

“No,” I said honestly.

“Then why?” she pressed.

I swallowed.

“Because it was never about feeling better,” I said. “It was about doing what I could do. Being who I am.”

Margot went quiet.

Then she whispered, “Mom would be proud.”

That landed harder than anything else.

My mother—who used to water her African violets and worry about plants while dying—would have wanted me to save the kid.

She would have wanted me to be kind even when it was hard.

She would have wanted me not to let bitterness become my whole personality.

Sometimes I hate how right she would have been.

Two more years passed.

Dad died on a Tuesday morning in March.

Margot called me at 6:12 a.m., and I answered half-asleep, confused, already bracing myself.

“It’s Dad,” she said, and her voice broke.

I sat up in bed so fast the room spun.

“He’s gone,” she whispered.

The grief that hit me wasn’t sharp.

It was heavy.

Like a blanket thrown over my head.

I flew to Ohio. Margot and I planned a small service. We played one of Mom’s favorite songs. We laughed a little, cried a lot. Lucas asked why Grandpa wasn’t waking up. Margot told him gently that Grandpa’s brain had been sick for a long time and now he was resting.

After the service, Margot and I sat in the parking lot in silence, the sky a hard Midwest blue.

“I’m sorry I wasn’t there more,” I said finally.

Margot stared out the windshield. “He didn’t know most days,” she said. “But when he did… he always asked about you.”

My throat tightened.

“He did?”

Margot nodded. “He’d say, ‘Where’s Cathy-girl? She’s saving people.’”

I covered my face with my hands and cried in the car like a child.

Because that was the tragedy of dementia: it steals your chances to say what you meant to say while the person is still able to hear it.

But it also leaves behind strange gifts—moments of clarity that feel like blessings.

“Do you think he forgave us?” Margot asked quietly.

“For what?” I said, wiping my face.

“For not being perfect,” she whispered.

I stared at her.

Then I reached over and took her hand.

“I think he loved us,” I said. “And that’s the only thing that matters.”

A month after Dad’s funeral, I got an email.

Subject line: Guest Lecturer Invitation — UCSF Pediatrics

I almost deleted it thinking it was spam.

Then I read the name at the bottom.

Dr. Oliver Stratton

My stomach flipped.

The email was polite, professional, warm. He wrote that he worked at a children’s hospital in San Francisco now. He wrote that he’d been asked to host a guest lecture series on rare pediatric neurovascular cases and would be honored if I’d speak.

He wrote:

I don’t know if you remember me. You saved my life when I was eight. I remember waking up and you telling me it was gone. I became a doctor because of that moment.

I stared at the screen until my eyes burned.

I forwarded it to Denise without comment.

She called five minutes later screaming.

“OH MY GOD,” she yelled. “YOU HAVE A FANBOY DOCTOR CHILD. YOU’RE LIKE BATMAN BUT WITH BETTER INSURANCE.”

I laughed, startled by the sound of it.

“Are you going?” Denise demanded.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“CAT,” she said, suddenly serious. “Go. This isn’t Richard. This is the kid. This is the reason you did it.”

I swallowed.

“Okay,” I whispered. “Okay. I’ll go.”

San Francisco smelled like salt and eucalyptus and expensive coffee.

Oliver met me in the hospital lobby wearing a white coat, stethoscope around his neck, hair darker now but the same stubborn set to his jaw.

For a second, I could see him in the Red Sox hoodie, shooting basketballs and refusing to quit.

He smiled when he saw me.

It was a normal smile—slightly crooked, like mine.

“Dr. Weiss,” he said, and his voice was deeper than I expected, warm. “Thank you for coming.”

I stared at him, throat tight.

“You’re… tall,” I managed.

He laughed. “Yeah, apparently the brain surgery didn’t stunt my growth.”

I snorted, surprised.

He gestured toward a café area. “Can I buy you coffee? Or is that weird?”

“It’s not weird,” I said. “It’s… life.”

We sat with paper cups between us.

“I want to say something,” Oliver said, suddenly serious. “I don’t remember everything from when I was a kid. But I remember your voice. I remember you looking at me like I mattered. Not like I was a problem to solve. Like I was a person.”

My eyes stung.

“That’s because you were,” I said.

He nodded. “My dad—” He hesitated.

The name still had weight.

“I don’t have a relationship with him anymore,” Oliver said quietly. “Not really. After I turned eighteen I moved out. It’s complicated.”

I studied him. “How is he?”

Oliver’s mouth tightened. “He’s alive. He lives somewhere warm. Florida, I think. He sends letters sometimes. Apologies, mostly. I don’t know what to do with them.”

Diane’s voice echoed in my head: Even when he’s sorry, it’s still about him.

“I heard he stopped operating,” I said carefully.

Oliver nodded. “He told me his hands weren’t steady anymore. He said it was age. But…” Oliver’s eyes flicked to my face. “My mom told me things. About him.”

My chest tightened. “What did she tell you?”

He swallowed. “That he hurt people.”

I didn’t answer.

Oliver’s gaze held mine. “He hurt you,” he said softly, like he was naming something sacred and terrible.

I exhaled slowly.

“Yes,” I said.

Oliver’s jaw clenched. “I’m sorry.”

“You don’t have to apologize for your father,” I said.

“But I still feel like…” He shook his head. “Like his shadow follows me.”

I stared at him, seeing the weight he carried. A child grown into a man still hauling his father’s mess like luggage.

“You’re not his shadow,” I said firmly. “You’re your own person. You chose pediatrics. You chose kids. That’s you.”

Oliver’s eyes shone. He blinked fast like he refused to cry in public.

“Sometimes,” he said, voice rough, “I wonder if he used me to get to you. Like asking for you was about him, not me.”

My stomach turned.

“I wondered that too,” I admitted.

Oliver stared at the table. “So why did you do it?”

I didn’t hesitate.

“Because you were eight,” I said. “Because you didn’t get to choose any of this. Because if I walked away, I wouldn’t be able to live with myself.”

Oliver nodded slowly.

Then he smiled—small, real.

“That’s why you’re my hero,” he said.

I swallowed hard.

“I don’t want to be anyone’s hero,” I whispered.

“Too late,” Oliver said, and the corner of his mouth lifted. “Also, I invited you to lecture, so you’re kind of contractually obligated now.”

I laughed, surprised again.

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll be your hero for one day.”

Oliver grinned. “Deal.”

The lecture went well.

I spoke to a room of residents and med students—tired, hungry, eager. I showed imaging, talked about decision-making, about anatomy and humility and the terrifying responsibility of choosing to operate when the risk is high.

A resident asked, “How do you decide when the personal context is… complicated?”

The room went quiet.

Oliver watched me from the back, expression unreadable.

I took a breath.

“You decide,” I said, “by remembering the patient isn’t your battlefield. They’re not your revenge. They’re not your guilt. They’re a person. And you have to be the kind of doctor you’d want if it were your kid on the table.”

Afterward, Oliver walked me out.

At the entrance, he hesitated.

“There’s something else,” he said.

“What?” I asked.

He pulled an envelope from his bag. “My dad… sent this to me last year. He told me to give it to you if I ever saw you again.”

I stared at the envelope like it might bite.

“Do you want it?” Oliver asked gently. “If not, I’ll throw it away.”

I thought about Diane. Denise. Margot. Dad calling me Cathy-girl. My own face in the mirror.

“I’ll take it,” I said.

Oliver handed it over like he was passing me something fragile.

“Whatever it is,” he said, “you don’t owe him anything.”

“I know,” I said.

We hugged—brief, careful, the kind of hug doctors give when they’re trying not to cross lines.

Then I walked away with the envelope in my bag and a strange, steady feeling in my chest.

Not forgiveness.

Not closure.

Something like peace.

Back in my hotel room, I sat on the bed and stared at the envelope for a long time.

Then I opened it.

Inside was another letter in Richard Stratton’s neat handwriting.

He wrote that he was older now, that his hands had failed him, that he’d spent years trying to understand what he’d done to the people he’d hurt. He wrote that he didn’t deserve forgiveness and wasn’t asking for it.

He wrote that he’d set up a fund—anonymous—supporting reconstructive surgery for patients harmed by elective procedures and for survivors of medical misconduct. He wrote that Diane had helped him do it, that Oliver didn’t know the details because Richard didn’t want credit.

Then he wrote:

I told myself I didn’t do it on purpose, because I needed to believe I was still a good man. But I also know I let anger live in my hands that day. Whether that counts as intent, I’ll leave to God.

My throat tightened.

He ended with:

If there is any justice, it’s that my son became a better man than I ever was. That’s because of you, not me.

I folded the letter and sat there in silence, feeling the strange ache of a truth that isn’t clean.

He didn’t confess fully.

He didn’t absolve me of doubt.

But he named something real: anger in his hands.

Maybe that was as close to honesty as he could get.

I thought about my scar.

And for the first time, I realized I didn’t need a perfect answer to move forward.

Some questions stay open forever.

You don’t close them.

You learn to carry them.

The next morning, before my flight home, I stood in the hotel bathroom and looked at my face.

I traced the scar.

Watched my smile pull slightly uneven.

Then I did something I’d never done.

I smiled anyway.

Not because I was happy.

Because I was alive.

Because I had done good in a world where good doesn’t always get rewarded.

Because an eight-year-old boy had grown into a doctor who cared about kids.

Because my mother’s love had survived in me like a seed.

Because my father’s last clear words to me had been pretty, always pretty.

And because Richard Stratton—whatever he was, whatever he’d done—no longer got to own the story of my face.

I did.

When I got home, I put Richard’s new letter in the same drawer as the old business card and the first letter.

Then I closed the drawer.

Not locked.

Just closed.

Like a chapter you don’t need to reread every night.

Denise texted me as I sat in my car outside my apartment.

So? Did you cry? Did he propose? Did you become besties with the child you saved? Give me DETAILS.

I laughed and typed back:

He’s a doctor. He’s fine. I’m fine. Also I’m never letting you call me Batman again.

Denise replied instantly:

Too late. Gotham needs you, Dr. Weiss.

Outside, it started to rain—soft, gray, the kind of rain that makes everything look newly washed.

I sat for a minute before turning the key.

And for the first time in years, when I looked in the rearview mirror, I didn’t see a ruined face.

I saw a face that had survived.

A face that had chosen.

A face that—scar and all—was mine.