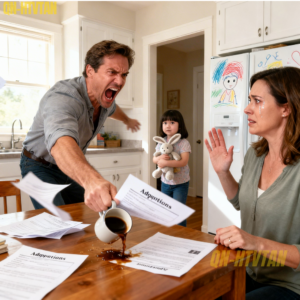

My Husband Pushed The Adoption Papers Back Across The Table, Look At Me And Casually Said, “I’m Not Putting My Name On Something Defective.”

The papers sat between us like a silent accusation. Crisp, white, official. Adoption papers—edges perfectly aligned, a neat little stack of hope that I had printed at the office on my lunch break, thinking this would be the next chapter for our family. But Vincent didn’t touch them. He just stared, his thumb tracing the rim of his coffee cup, the steam curling upward between us.

Rosie was asleep upstairs, her stuffed rabbit tucked under her chin, her small hand resting against her cheek. She’d had a good day—she always did. That morning, she’d woken up early to “make breakfast” for me: toast burned on one side, a glass of milk filled to the very brim. When Vincent came down, she’d hugged his leg and called him Daddy. She’d been calling him that for months now, ever since the wedding. I thought it melted his heart every time. I thought it meant something.

Now he looked at the papers like they were something dangerous. “You really want me to sign these tonight?” he asked, his tone too casual.

“I thought you’d want to,” I said softly. “It’s just… making official what’s already true. You’re her dad, Vincent.”

He didn’t answer right away. His eyes dropped to the first page. He leaned forward, reading, lips pressed tight. He looked like he was calculating something, not feeling it. Then, without looking at me, he pushed the papers back across the table.

“I’m not signing them,” he said.

The words didn’t register at first. “What?”

“I said I’m not signing.”

The kitchen felt smaller suddenly. The refrigerator hummed too loud, the clock ticked like it was mocking me. “Why not?” I asked. “I don’t understand.”

He sighed and leaned back, arms crossed. “Because I’ve been thinking about this. And I don’t want that kind of responsibility. Not legally.”

“Responsibility?” I repeated. “She’s already your responsibility, Vincent. She’s your family.”

He shook his head like I’d missed the point. “Not legally, she’s not. Look, I love Rosie, okay? She’s a great kid. But I have to be realistic. She’s going to need care for her whole life. That’s just the truth. If something happens to us—if we split up—I’d be on the hook for that forever.”

I stared at him, unable to speak for a moment. “You’d be on the hook for her?” I said finally. “That’s how you see it? Like she’s a debt?”

He frowned, defensive now. “Don’t twist my words. I’m saying it’s a huge commitment. It’s not something you just sign because it looks nice in a frame.”

I reached for the papers, my hand shaking a little. “You said you loved her. You said she was yours.”

“I do love her,” he said quickly. “But love doesn’t mean I have to make it legal.”

“Why not?”

He hesitated. I could see the lie forming before he spoke it. “Because it’s complicated. Because I have to think about my future too. What if something happens? What if she—”

“What if she what?” I asked quietly.

He looked right at me then, his eyes cold and steady. “What if she never grows up? What if she can’t live on her own? What if I’m sixty years old and still paying for a kid who isn’t mine?”

It was like all the air had been sucked out of the room. I couldn’t move. “She is yours,” I said, my voice shaking. “You married me. You said—”

“I said I’d be there for you,” he interrupted. “And I am. But this—this is different.”

I felt something in my chest snap. “Different how?”

He exhaled through his nose, as if the conversation bored him. “Because I’m not putting my name on something defective.”

The words landed like a slap. I blinked at him, certain I’d misheard. “What did you just say?”

“I said I’m not putting my name on something defective,” he repeated, slower this time, like he was explaining it to a child.

For a moment, I couldn’t feel my hands. My voice came out low, strangled. “Defective? You’re calling my daughter defective?”

He shrugged, completely calm. “I’m being realistic, not cruel. You can’t pretend she’s normal, Jenna. You know what I mean. She’s—she’s special needs. It’s sad, but it’s true.”

“Don’t,” I said sharply. “Don’t say that.”

He looked annoyed now, as if I was being unreasonable. “I’m not trying to hurt your feelings. I’m just saying what everyone else is too polite to admit. She’s always going to need help. Always. I can’t—”

“You can’t what? Love her?”

He rubbed his temples. “I can love her, I just have to be smart about it. You don’t know what it’s like to think ahead like that. You let your emotions drive everything.”

I was shaking now, but not from sadness—from something colder. “You met her when she was four,” I said slowly. “You told me she was the sweetest kid you’d ever met. You said you loved that she hugged everyone. You said—”

“I said a lot of things,” he interrupted. “I was trying to make things work. I didn’t know what it would really be like.”

“What it would really be like?” I repeated, almost whispering. “You mean having a child who laughs every morning, who says ‘I love you’ fifty times a day? Who thinks every stranger is beautiful? That’s what you didn’t expect?”

He looked away. “You’re not hearing me.”

“No,” I said. “I’m hearing you just fine.”

We sat there in silence for a long time. The papers were still between us, his fingerprints smudging the top page where he’d pushed them away. Somewhere upstairs, the floor creaked. Rosie rolled over in bed. The sound made my throat tighten.

Finally, I asked, “Did you ever actually love her?”

He didn’t look at me. “Of course I did,” he said. “I just… loved her from a distance. There’s nothing wrong with protecting myself.”

“From what?” I asked, my voice breaking. “From a little girl who thinks you hung the moon?”

He sighed again, the kind of sigh people give when they’re done explaining themselves. “You’re overreacting, Jenna. This doesn’t change anything. We can still be a happy family without all this legal nonsense. The paperwork doesn’t make me her father.”

I stared at him. “You’re right,” I said softly. “It doesn’t.”

He looked at me then, frowning like he couldn’t understand why I was so upset. “You’re too emotional,” he said. “You’re making this bigger than it needs to be.”

Continue below

My daughter, Rosie, was 6 years old when I married Vincent. She had been in my life since the day she was born. She had Down syndrome and she was the most joyful person I had ever known.

She laughed at everything. She hugged strangers. She told every person she met that they were beautiful. Rosie was not defective. Rosie was perfect. Vincent knew about Rosie before we started dating. He met her on our third date because I didn’t believe in hiding the most important part of my life. He said she was adorable. He said he loved kids.

He said having a child with special needs didn’t scare him at all. He said all the right things. He said them so convincingly that I believed him. We dated for 2 years before he proposed. During that time, Vincent was good with Rosie. He played with her. He read her stories. He came to her school events and clapped when she performed in the holiday show.

He seemed like a man who genuinely cared about my daughter. I thought I had found someone who would love both of us. We got married in a small ceremony at a vineyard. Rosie was the flower girl and she threw petals everywhere, including at the afficient. Everyone laughed. Vincent laughed, too. He picked her up and spun her around and called her his best girl.

I cried because I was so happy. 6 months after the wedding, I brought up adoption. Rosie’s biological father had never been in the picture. He signed away his rights before she was born and disappeared. Vincent was the only father figure she had ever known. I thought making it official would be beautiful. I thought Vincent would be honored.

I brought home the paperwork and spread it on the kitchen table after Rosie went to bed. I explained what each form meant. I showed him where to sign. I told him we could have a little celebration afterward. Maybe take Rosie to get ice cream and tell her the good news. Vincent looked at the papers for a long time.

Then he pushed them back across the table toward me. He said he wasn’t going to sign. I asked why. He said he had been thinking about this and he didn’t want the legal responsibility. I asked what legal responsibility he was worried about. He said Rosie would need care for her entire life. He said people with Down syndrome couldn’t live independently.

He said if something happened to our marriage, he would be on the hook for supporting her forever. I reminded him that Rosie was already part of our family. I reminded him that he had known about her from the beginning. I reminded him that he had stood at our wedding and promised to love and cherish both of us. He said that was different.

He said loving someone and legally binding yourself to them were two separate things. He said I shouldn’t take it personally. Then he said the words I will never forget. He said he wasn’t putting his name on something defective. I asked him to repeat himself because I was sure I had misheard. He said it again.

He said Rosie was defective and he wasn’t going to legally claim a defective child. He said it calmly like he was explaining a reasonable decision. Like he was declining an extended warranty on a car. Like my daughter was a product that didn’t meet his standards. I didn’t yell. I didn’t cry. I sat there looking at the man I had married and I realized I had made a terrible mistake.

Not about Rosie, about him. I asked him if he had ever actually loved my daughter. He said of course he loved her. He said he just loved her from a safe distance. He said there was nothing wrong with protecting himself financially. He said I was being emotional and not thinking clearly. He said we could still be a happy family without him signing papers.

He said the paperwork didn’t change anything. I told him the paperwork changed everything. I told him a father doesn’t call his child defective. I told him a husband doesn’t refuse to commit to his wife’s daughter after promising to love them both. He said I was overreacting. He said plenty of stepparents never adopted their stepchildren.

He said I was making this into a bigger issue than it needed to be. I slept in Rosie’s room that night. She asked me why I was on the floor next to her bed. I told her I just wanted to be close to her. She said, “Okay, mama.” And fell asleep holding my hand. She didn’t know that her stepfather had just called her defective.

She didn’t know that the man who read her bedtime stories saw her as a liability. She just knew that her mother was there, and that was enough for her. The next week, I contacted a divorce lawyer. I found her name in a support group form at 2:00 in the morning while Rosie slept beside me. Someone had posted about needing a lawyer who understood special needs families, and three people recommended Aurelia Whitley.

I called her office the moment it opened and explained I needed help with a divorce. Her secretary started to give me an appointment for next week, but then Aurelia picked up the line herself. She asked me to tell her what happened. I said my husband refused to adopt my daughter and called her defective. There was silence on the other end.

Then Aurelia said she could see me at 3 that afternoon, and something in my voice told her this was urgent. Her office was in a brick building downtown with accessible ramps and wide doorways. The waiting room had toys in one corner and books about special needs parenting on the shelves. I sat across from Aurelia at her desk and started talking.

She took notes on a yellow legal pad and never interrupted. I told her about Vincent’s promises and the wedding and Rosie throwing flower petals. I told her about the adoption papers and the words I couldn’t stop hearing. When I finished, Aurelia sat down her pen and looked at me. She said she had a daughter with cerebral palsy who was 9 years old.

She understood exactly what Vincent’s words meant and why I couldn’t stay. Aurelia pulled out a fresh legal pad and started outlining the divorce process. California was a no fault state, which meant Vincent’s reasons for refusing adoption wouldn’t matter in court. The law didn’t care that he called my daughter defective.

What mattered was dividing our assets, figuring out support payments, and moving forward as quickly as possible. She explained filing timelines and mandatory waiting periods. She talked about discovery and disclosure requirements. Her voice was calm and professional, but I saw anger in her eyes when she mentioned Vincent’s name.

I asked about custody, and Aurelia’s expression softened. Vincent had no legal relationship to Rosie, so custody wasn’t an issue. Rosie was mine completely and would stay that way. The concern was spousal support and asset division since we’d only been married 6 months. California had formulas for calculating support based on income and marriage length.

She would need my financial documents and Vincent, too. She warned me that short marriages sometimes meant minimal support, but she would fight for what I deserved. I drove home with the retainer agreement signed and a list of documents to gather. Vincent’s car was in the driveway when I pulled up. I found him in the living room watching television like nothing had changed.

I stood in front of the screen and told him I’d hired a divorce attorney and would be filing papers. His face went blank with shock. He actually looked surprised, like he’d expected me to just accept his decision and move on without any problems. Vincent stood up and immediately switched into damage control mode.

We should try marriage counseling first. We could work through this. Every marriage had rough patches. I reminded him that you can’t counsel someone into loving your child or into not calling her defective. Those words came from somewhere deep inside him, and no therapist could fix that. He reached for my hand, but I stepped back.

His face changed then, and anger replaced the fake concern. I was overreacting. I was throwing away our marriage over paperwork. Plenty of couples disagreed about adoption and stayed together. I was being emotional and not thinking about what divorce would do to Rosie. I stood there feeling nothing but cold certainty as he tried to rewrite what happened.

He kept talking and I kept seeing him push those papers across the table. I kept hearing the word defective in his calm, reasonable voice. I went upstairs and pulled two suitcases from the closet. I packed clothes for Rosie and myself, her favorite stuffed animals, her medications and medical records. Vincent followed me around asking what I was doing.

I told him we were leaving. He said I couldn’t just take Rosie away from her home. I reminded him this was my home before it was his. And Rosie was my daughter before he ever met us. I loaded the suitcases into my car and went back for Rosie. She was coloring at the kitchen table and looked up with her bright smile when I said we were going to grandma’s house.

Mom lived across town in the house where I grew up. She opened the door and took one look at my face before pulling me into a hug. Rosie ran past us to the toy box mom kept in the corner of the living room. Mom didn’t ask questions right away. She just held me while I stood there trying not to fall apart.

Then she made tea and we sat at her kitchen table while Rosie played. I told mom everything. I told her about the adoption papers and Vincent’s refusal and the legal responsibility he didn’t want. I told her about the word defective that I couldn’t stop hearing in my head. Mom got very quiet. She held her teacup and stared at the table for a long moment.

Then she said she’d never fully trusted Vincent, but she’d hoped she was wrong. She said something about him always seemed performed, like he was playing a role instead of being himself. She’d seen how he acted with Rosie at family gatherings and thought maybe she was being too critical. Now she knew her instincts had been right.

Rosie adjusted to staying at grandma’s house with the easy way kids have of accepting change. She explored mom’s guest room and claimed the bed by the window. She helped mom make dinner and set the table with careful concentration. At bedtime, she asked when we were going home. I told her we were having an adventure at grandma’s house for a while.

She said okay and asked if we could make pancakes in the morning. That was enough for her. She fell asleep holding her stuffed rabbit while I sat on the floor next to her bed and tried to figure out what came next. 3 days later, Aurelia filed the divorce petition at the courthouse and arranged for a process server to deliver the papers to Vincent at his office.

She called me that afternoon to confirm everything went through. Vincent called me less than an hour after being served. His voice came through my phone so loud I had to pull it away from my ear. He demanded to know why I had him served at work where everyone could see. He said his co-workers watched the process server hand him papers in the middle of a meeting.

He said I embarrassed him in front of his boss and his entire team. I asked if he really thought I cared about his embarrassment after what he said about Rosie. He said I was being vindictive and petty. He said I could have had him served at home instead of making a scene at his workplace.

I told him the process server went where he was during business hours and that was standard procedure. He kept talking about his reputation and how this made him look to his colleagues. He never once mentioned losing his family or wanting to fix things between us. He just cared about what other people thought.

I hung up while he was still talking and turned off my phone for the rest of the day. Vincent’s attorney contacted Aurelia the following week with a proposal for mediation. Aurelia called me to explain that Vincent wanted to settle everything quickly and quietly through a mediator instead of going to court.

She said mediation could work well if both people wanted to negotiate fairly and reach an agreement, but she had serious doubts about whether Vincent would negotiate in good faith. She reminded me that he was more worried about his image than about our marriage ending. She said people like that usually tried to control the process and intimidate the other person into accepting less than they deserved.

I asked if we should refuse mediation and just go straight to court. She said we should try mediation first because judges like to see that both parties attempted to work things out. If mediation failed, we would have a stronger position in court. I agreed to try it even though I knew Vincent would make it difficult.

Brianna showed up at mom’s house two nights later with three bottles of wine and enough Chinese takeout to feed six people. She arrived after Rosie went to bed and spread everything across mom’s kitchen table. She hugged me for a long time before saying anything. Then she poured wine into two glasses and told me to sit down and eat.

Brianna and I met in college during freshman orientation and stayed friends through everything that came after. She knew me before Vincent existed in my life. She was there when Rosie was born and held my hand through all the early appointments and therapy sessions. She never questioned my decisions or made me feel like Rosie was a burden.

Having her support now felt solid and real in a way that Vincent’s fake acceptance never did. We ate lain and drank wine while mom watched television in the living room. Brianna asked if I was completely sure about the divorce. She said she supported me no matter what, but wanted to make sure I had thought through everything. I told her this wasn’t really about the adoption papers themselves.

It was about discovering that the man I married saw my daughter as a liability instead of a person. It was about him calling Rosie defective like she was a broken product he didn’t want to own. I explained that you can’t come back from words like that. You can’t fix a relationship with someone who thinks your child is less than human.

Brianna nodded and refilled my wine glass. She said she never fully trusted Vincent, but hoped she was wrong about him. She said something always seemed off about how he acted around Rosie, like he was performing kindness instead of actually feeling it. Now she knew her instincts were right. The first mediation session happened 2 weeks after Aurelia filed the petition.

We met in a conference room at the mediator’s office downtown. Vincent arrived with his attorney looking confident and put together in an expensive suit. He smiled at me like we were about to have a friendly conversation about something simple. The mediator introduced himself and explained the ground rules for the session.

Vincent interrupted before we even started the actual discussion. He said he wanted to propose something before we got into dividing assets and talking about support payments. He said we should reconcile and forget about the divorce entirely if I would just drop my unreasonable expectations about adoption. He said we could go back to being happy together as long as I stopped pushing him to legally claim Rosie.

I looked across the table at Vincent and felt absolutely nothing except cold clarity. I told him there would be no reconciliation under any circumstances. I said we were here to discuss asset division and support obligations, not to negotiate about saving our marriage. His face changed completely when I said that. His confident smile disappeared and his expression hardened into something ugly and mean.

I saw the exact same look he had when he pushed those adoption papers back across our kitchen table. The mediator tried to redirect the conversation, but Vincent kept staring at me like he couldn’t believe I was refusing to consider his offer. His attorney jumped in and started arguing that Vincent shouldn’t owe any spousal support because our marriage was so brief.

He said 6 months wasn’t long enough to create any real financial dependency. Aurelia pulled out the folder she brought and calmly explained that I left my job to move across the state for Vincent’s career opportunity. She said I gave up my position and my professional network to support his advancement. She said that absolutely changed my financial situation and created a legitimate claim for support during my transition back to employment.

Vincent’s attorney tried to argue that I chose to leave my job and Vincent didn’t force me. Aurelia pointed out that spouses make sacrifices for each other’s careers all the time and the law recognized that as creating support obligations. The mediation session lasted two hours and ended without any agreement.

Aurelia had predicted this would happen. Afterward, she explained that Vincent was still in the denial phase where he thought he could control the outcome through intimidation and manipulation. She said he expected me to back down and accept whatever he offered just to avoid conflict. But I wasn’t that person anymore.

I learned what it meant to protect my daughter even when it cost me everything else. Back at mom’s house that evening, Ros’s school called while I was making dinner. Her teacher said Rosie had been asking about Vincent during circle time that day. She wanted to know how to handle questions about family changes in an age appropriate way.

She said Rosie told the other kids that Vincent didn’t live with us anymore, and some of the children asked why. The teacher wasn’t sure what to tell them or how to support Rosie through this transition. She suggested I come in to meet with her and the special education coordinator to discuss how to help Rosie process the separation.

I scheduled a meeting for the next afternoon and drove to Rosie’s school right after lunch. The teacher and the special education coordinator sat with me in a small conference room decorated with children’s artwork. I explained that Vincent and I were separating and going through a divorce. I told them Vincent had decided he didn’t want to legally adopt Rosie, even though he had been acting as her stepfather.

I didn’t mention the word defective or explain exactly what Vincent said because I couldn’t make myself repeat it out loud. They were both kind and supportive. They helped me understand how to talk to Rosie about family changes without overwhelming her with information she couldn’t process. They said children Rosie’s age understood concrete things better than abstract concepts.

They suggested I focus on what would stay the same in her life rather than everything that was changing. They offered to support Rosie at the school and watch for any signs she was struggling with the transition. I left that meeting feeling grateful that Rosie had people who cared about her well-being beyond just her academic progress.

That evening, I sat with Rosie at the small table in mom’s kitchen where she was coloring a picture of butterflies. I waited until she finished adding purple to the wings before I spoke. I told her that Vincent and I weren’t going to be married anymore. I explained that he was going to live somewhere else and we would stay here with Grandma for now.

I promised her that she would always have me and Grandma and everyone who loved her. Rosie put down her crayon and looked at me with those eyes that always saw straight through to what mattered. She asked if it was because she did something wrong. The question hit me like a punch to the chest because of course she would think that.

Children always blame themselves when adults fall apart around them. I pulled her onto my lap and held her close. I told her she didn’t do anything wrong at all. I explained that sometimes grown-ups make decisions that have nothing to do with kids. I said that Vincent and I had problems that were only about us and never about her.

She was quiet for a moment, processing this in whatever way her brain worked through complicated things. Then she asked if she could have mac and cheese for dinner. Just like that, she moved on because children are better at accepting what they can’t control. I made her the mac and cheese and watched her eat it while telling me about a boy at the school who could whistle through his teeth.

My phone started buzzing that night after Rosie went to bed. Vincent sent a text saying he missed us. 10 minutes later, another message came through calling me vindictive for taking Rosie away. Then another apology, then an accusation that I was being unreasonable and throwing away our marriage over nothing. The messages kept coming over the next few days, sometimes loving and sometimes angry.

He would text that he wanted to work things out, then follow it up by saying I was manipulating the situation. One message begged me to come home. The next one blamed me for ruining everything. I showed the messages to Aurelia during our next meeting at her office. She read through them with a tight expression on her face. She told me to stop responding completely and let all communication go through the attorneys from now on.

She explained that his back and forth contact was a manipulation tactic designed to keep me emotionally engaged and offbalance. She said abusers and manipulators use this pattern to maintain control when they felt it slipping away. I hadn’t thought of Vincent as abusive, but hearing her say it made something click into place.

He was trying to keep me confused and reactive, so I wouldn’t think clearly about what I needed to do. The financial disclosure documents arrived in a thick envelope 2 weeks later. Aurelia had requested complete records of all our accounts and assets as part of the divorce proceedings. I sat at mom’s kitchen table going through page after page of bank statements and investment records.

That’s when I found accounts I didn’t know existed. Vincent had opened a separate savings account at a different bank and had been transferring money there throughout our marriage. There were investment accounts in his name only that I had never seen before. I called Aurelia immediately and she came over that same afternoon to review everything with me.

She spread the papers across the table and pointed out the pattern of transfers and deposits. She said this was common when someone anticipated divorce and wanted to hide assets from their spouse. She said it showed planning and intention to protect his money regardless of what happened to the marriage.

We filed a motion for full financial discovery the next day. Aurelia requested bank statements, investment account records, credit card statements, and documentation for any assets Vincent might have. His attorney objected within 48 hours, claiming our requests were too broad and invaded Vincent’s privacy. Aurelia fired back with a response, explaining that California law required full financial disclosure and divorce proceedings, and Vincent’s objection suggested he had something to hide.

The judge ordered Vincent to comply with our discovery requests within 30 days. Aurelia looked satisfied when she called to tell me about the judge’s ruling. She said Vincent’s attorney had overplayed their hand by objecting so strongly, which made the judge suspicious. During all of this legal back and forth, I started seeing a therapist named Matilda Vaughn, who specialized in families with special needs children.

Brianna had recommended her after I mentioned feeling overwhelmed by everything happening at once. Matilda’s office was in a quiet building near the hospital with plants in every corner and soft lighting that made the space feel calm. She asked me to talk about Rosie first, not about Vincent or the divorce. I described my daughter’s personality, her joy, her struggles at the school, her love of purple and butterflies and mac and cheese.

Matilda smiled and said she could tell how much I loved Rosie just from the way I talked about her. Then she asked about the marriage and I told her everything, including the word defective that still echoed in my head. She helped me understand how to process the grief of my failed marriage while still managing Rosie’s daily needs and therapy appointments and school schedule.

In one session about 3 weeks after I started seeing her, Matilda pointed out something I hadn’t noticed about myself. She said, “I had been so focused on protecting Rosie from Vincent’s rejection that I hadn’t let myself feel the full weight of his betrayal.” She said, “I was carrying anger and grief and shock, but I kept pushing those feelings down because I thought I needed to stay strong for my daughter.

” She asked me what would happen if I let myself actually feel everything Vincent had done. I started crying before I could answer. I cried about the future I thought we would have together. I cried about believing his lies for 2 years. I cried about introducing him to my daughter and letting her get attached to someone who saw her as defective.

I cried until my throat hurt and my eyes were swollen and Matilda just sat there handing me tissues and letting me fall apart in her office where Rosie couldn’t see. The full financial discovery results came back 6 weeks after we filed the motion. Aurelia called me to her office to go through everything together.

She had the documents organized in folders with tabs marking the important sections. She showed me an investment account that Vincent had opened 2 months before our wedding. He had been depositing money there consistently throughout our entire marriage, building up a separate fund that I knew nothing about.

The account had over $40,000 in it. Aurelia looked at me across her desk and said, “This suggested planning and intention.” She said, “Vincent had been protecting his exit strategy from the very beginning, even before we got married. He had been preparing for our marriage to fail while I was picking out wedding flowers and writing vows.

I sat there staring at the account statements with their neat rows of deposits and dates. I felt vindicated because this proved I wasn’t crazy or overreacting like Vincent claimed, but I also felt angry in a way that made my hands shake. This was evidence that Vincent had never been fully committed to our family.

He had always kept one foot out the door, always protected himself first, always seen our marriage as temporary. While I was building a life together, he was building an escape route. While I was trying to blend our family, he was hiding money in case it didn’t work out. While I was falling in love with the idea of forever, he was planning for the end.

My phone rang 3 days after the financial discovery results came through. I didn’t recognize the number, but answered anyway because everything felt urgent during the divorce. A man’s voice said my name like a question and then introduced himself as Gerard, Vincent’s brother. I hadn’t spoken to Gerard since the wedding where he gave a short toast about family and commitment.

He lived in Oregon and worked in forestry, so Vincent rarely mentioned him. Gerard said he heard about the divorce from their mother and wanted to apologize for his brother’s behavior. He said Vincent told him about refusing the adoption and calling Rosie defective. Gerard’s voice got tight when he said that word like it physically hurt him to repeat it.

He explained that their father walked out when Vincent was 8 years old. just left one morning for work and never came back. Their mother found divorce papers in the mail 6 weeks later. Gerard said Vincent spent years waiting for their dad to return and explain why they weren’t good enough to stay for.

He said Vincent developed this fear of being trapped in situations he couldn’t escape from. Gerard tried talking to Vincent about therapy multiple times over the years. He said Vincent needed help processing the abandonment and learning that commitment wasn’t the same as being trapped. Vincent always refused. He said therapy was for people who couldn’t handle their own problems.

Gerard told me he wasn’t making excuses for Vincent’s behavior toward Rosie. He said understanding why someone acts terribly doesn’t make their actions acceptable. He said Vincent’s fear explained his choices, but didn’t justify calling a child defective or refusing to commit to someone he claimed to love.

Gerard said he thought I was doing the right thing for Rosie by leaving. He said she deserved better than living with someone who saw her as a liability instead of a person. I thanked Gerard for calling and told him I appreciated knowing the background. After we hung up, I sat with this new information about Vincent’s childhood. It made sense in a sad way.

Vincent protected himself by never fully committing to anything that might hurt him if it ended. He kept that investment account secret because he always planned for failure. He refused to adopt Rosie because he imagined our marriage ending and himself stuck supporting a child he never wanted legal ties to.

His damage explained everything, but it didn’t change what he did to my daughter. Understanding Vincent better didn’t make me forgive him. It just made me sad that he let his past destroy any chance at a real future. The second mediation session happened 2 weeks after the financial discovery. Vincent walked into the conference room looking different from the first time.

His confidence was gone. He sat across from me and his attorney with his shoulders slightly hunched. His lawyer opened by acknowledging that the financial discovery revealed assets they should have disclosed initially. She said they wanted to propose a fair settlement to resolve everything quickly. Vincent’s attorney laid out terms that included splitting our assets evenly and providing me with limited spousal support for 6 months.

She said this reflected the brief length of our marriage while acknowledging that I had relocated for Vincent’s job. I looked at Aurelia and she made notes on her legal pad without reacting. After Vincent’s attorney finished, Aurelia asked for time to review the proposal with me privately. We moved to a smaller room down the hall.

Aurelia spread the proposal across the table and pulled out her own calculations. She pointed to the spousal support section and said, “6 months wasn’t enough time for me to rebuild my career after relocating.” She showed me case law from similar situations where courts awarded support for longer periods. She circled the asset division and noted several items that weren’t properly valued.

She said we could negotiate better terms because the hidden investment account damaged Vincent’s credibility. We spent an hour crafting a counter proposal. Aurelia suggested asking for one year of spousal support to give me time to find stable employment and establish our new household. She calculated a monthly amount based on Vincent’s actual income, including the money he had been hiding.

She also adjusted the asset division to account for the furniture and household items I would need to set up an apartment. We went back to the main conference room and Aurelia presented our counter offer. Vincent’s face got red when he heard the support amount. He said he couldn’t afford that much. Aurelia pulled out the bank statements and investment account records.

She walked through Vincent’s actual monthly income and expenses. The numbers proved he could easily afford what we were asking. His attorney looked uncomfortable as Aurelia laid out the evidence. Vincent tried arguing that the investment account was for his retirement. Aurelia pointed out that he opened it 2 months before our wedding, which suggested it wasn’t a standard retirement fund.

She said a judge would likely view it as hidden marital assets. Vincent’s attorney called for another break. When they came back 20 minutes later, she proposed a compromise. 10 months of spousal support at the amount we requested, plus a lump sum payment from the asset division. Vincent sat with his arms crossed, looking angry, but defeated.

Aurelia reviewed the numbers and nodded at me. I accepted the settlement. Aurelia explained that sometimes the best outcome is ending the conflict efficiently rather than fighting for maximum gain. She said dragging out the divorce would cost me money in legal fees and emotional energy I needed for Rosie. The settlement gave me enough financial cushion to move forward and rebuild our lives.

Vincent signed the agreement that day. His attorney said they would have the final paperwork drafted within a week. Walking out of the mediation, I felt lighter than I had in months. The marriage was essentially over. I just needed to wait for the court to make it official. I started looking at apartments the next day.

Mom’s house had been a safe place to land, but Rosie and I needed our own space. I wanted to stay near mom so she could help with Rosie and so Rosie could stay in her current school. Her teachers understood her needs and she had friends there. Moving to a new school district would disrupt her routine. Brianna came with me to look at rentals.

We drove through neighborhoods near mom’s house looking for buildings with available units. Most places were too expensive or too small. One landlord took one look at the paperwork where I listed Rosie as a dependent and said the unit wasn’t suitable for children with special needs. Brianna told him that was discrimination and we left.

The fourth apartment we visited was in a two-story building with a courtyard in the middle. The landlord was a woman named Jella who had raised three kids in the same building. She showed us a two-bedroom unit on the ground floor. The apartment had wide doorways and a walk-in shower with grab bars already installed.

Jella said the previous tenant was an elderly man who needed accessibility features. She asked about my daughter and I explained that Rosie had Down syndrome. Jella smiled and said her nephew had autism. She asked what Rosie liked to do. I told her about Rosie’s love for purple and butterflies and dancing. Jella said there was a community garden in the courtyard where Rosie could plant flowers if she wanted.

The rent was manageable with my settlement money and the part-time job I was starting the following week. I had found work at a nonprofit that provided resources for families with special needs children. The job paid less than my previous position, but the schedule was flexible and the mission felt meaningful. I filled out the rental application while Brianna measured the bedrooms to figure out furniture arrangements.

Jella said she would run my background check and call me within 2 days. Walking back to the car, Brianna hugged me and said the apartment was perfect. I let myself feel hopeful for the first time since Vincent pushed those adoption papers away. Aurelia called the next week and said she had someone I should talk to, a financial adviser who specialized in planning for families with special needs children.

She said managing my settlement money wisely would make a huge difference in Rosie’s future. The adviser’s name was Caroline and she worked from a small office near the courthouse. I met with her on a Thursday morning after dropping Rosie at the school. Caroline had a daughter with cerebral palsy so she understood the costs involved in raising a child with disabilities.

She asked detailed questions about Rosie’s current needs and what I anticipated for her future. We talked about therapy costs, medical expenses, special education services, and what Rosie might need as an adult. Caroline explained special needs trusts, and how they work to protect government benefits while still providing extra support.

She said setting up a trust now would ensure Rosie had resources throughout her life, even after I was gone. We discussed government benefits that Rosie qualified for and how to navigate the application process. Caroline created a budget that accounted for our current expenses and built-in savings for future needs. She showed me how to invest part of the settlement to generate income while keeping enough liquid for immediate costs.

The meeting lasted 2 hours and I left with a binder full of information and action steps. Caroline scheduled a follow-up appointment to help me set up the special needs trust once the divorce was finalized. Driving back to mom’s house, I felt grateful that Aurelia had connected me with someone who understood our situation.

Planning for Ros’s future made everything feel more stable and secure. Caroline spread out papers showing different saving plans and investment options across her desk. She pointed to numbers representing therapy costs and medical expenses that would continue through Ros’s entire life. The figures looked huge at first, but Caroline broke them down into monthly amounts that felt more manageable.

She explained how the settlement money could work for us instead of just sitting in an account losing value to inflation. Part would go into a special needs trust that protected Rosie’s government benefits while still giving her extra support. Another portion would get invested in low-risk funds that generated steady income.

Caroline showed me how to budget for Rosie’s current needs while building savings for future expenses I hadn’t even considered yet. Things like adaptive equipment as she grew older, continued therapy into adulthood, and residential support if she ever wanted more independence. The planning made Rosie’s future feel less scary because I could see actual numbers and strategies instead of just worrying.

Caroline said many parents struggled alone without this kind of guidance, and I was already ahead by seeking help now. She scheduled another appointment to finalize the trust paperwork once the divorce became official. Leaving her office, I felt like I had a real plan instead of just hoping everything would work out somehow.

The courthouse hearing for our final divorce decree lasted less than 15 minutes. Vincent sat on the opposite side of the courtroom with his attorney and didn’t look at me once. The judge reviewed our settlement agreement and asked if we both understood the terms. We each said yes in turn. She signed the papers and declared our marriage legally dissolved.

6 months had passed since Vincent pushed those adoption papers across our kitchen table. 6 months since he called my daughter defective. Now we were strangers again in the eyes of the law. Walking out of the courthouse, I expected to feel sad or angry, but mostly I just felt tired. The relief surprised me because part of me was still grieving what I thought we had together.

All those moments that seemed real but apparently weren’t. The wedding where he spun Rosie around and called her his best girl. The bedtime stories he read to her. The school events where he clapped and smiled. I had believed in a version of Vincent that never actually existed. But now I felt free from the weight of pretending he was someone he wasn’t.

Free from watching my words around him. Free from worrying that Rosie would pick up on his hidden resentment. Free from the exhausting work of convincing myself that everything was fine when it clearly wasn’t. Jella called 2 days later to say the apartment was ours if we still wanted it. Brianna helped me pack up our things from mom’s house and moved them into the new place.

Rosie ran through the empty rooms laughing and asking which one was hers. I showed her the smaller bedroom with the window facing the courtyard. She pressed her face against the glass and pointed at the garden below. Jella had mentioned that the previous tenant grew tomatoes and herbs in raised beds. Rosie wanted to know if we could plant purple flowers.

I told her we absolutely could. That weekend, we went to the hardware store and let Rosie pick out paint samples. She chose a purple called Lavender Dreams that was lighter than I expected, but perfect for a little girl’s room. Brianna came over to help paint while Rosie was at the school. We covered the walls in two coats, and the color transformed the space into something magical.

When Rosie got home, she gasped and spun around in circles. I bought butterfly stickers at the craft store and Rosie placed them carefully on the walls near her bed. She wanted them to look like they were flying. The room became completely hers in a way our old house never allowed. Vincent had opinions about everything from paint colors to furniture placement.

This apartment held no memories of him. Every choice was mine and Rosie’s together. My first day at the nonprofit felt like walking into a place where people actually understood. The organization provided resources for families with special needs, children, including support groups, advocacy training, and connections to therapy services.

My co-workers welcomed me warmly during the morning staff meeting. Several mentioned having family members with disabilities. One woman’s son had autism. Another’s niece had cerebral palsy. They asked thoughtful questions about Rosie and shared stories about their own kids. The work involved coordinating family workshops, maintaining resource databases, and helping parents navigate school systems and government benefits.

Everything I had learned through raising Rosie and fighting through my divorce suddenly felt useful. My experiences weren’t just painful memories anymore. They were knowledge that could help other families facing similar challenges. The job paid less than my previous position, but the schedule was flexible and the mission felt meaningful.

I could pick Rosie up from the school most days. I could attend her therapy appointments without asking permission. I could build a life around her needs instead of trying to fit her into someone else’s schedule. 3 months after we moved into the apartment, Ros’s teacher requested a parent conference. I walked into the classroom expecting problems, but her teacher smiled and said Rosie seemed more relaxed and confident lately.

She participated more during circle time. She helped other students without being asked. She seemed happier overall. The teacher wondered if anything had changed at home. I explained that we had gone through a divorce and moved to a new apartment. The teacher nodded like this made perfect sense. She said, “Children often picked up on tension even when adults tried to hide it.

Rosie must have been feeling the stress in my marriage with Vincent even though I thought I was protecting her from it. Kids were more perceptive than we gave them credit for. Driving home from the conference, I realized Rosie had been carrying the weight of our broken household without any way to express it. She didn’t have the words to say that something felt wrong at home.

She just absorbed the tension and held it inside her small body. Now that we lived in our own space without Vincent’s hidden resentment filling the rooms, she could finally breathe. She could be herself without sensing that someone in the house saw her as less than whole. Brianna invited me to a single parent support group that met twice monthly at a community center near our apartment.

I hesitated at first because I didn’t want to spend evenings talking about my failed marriage, but Briana insisted it would help to connect with people who understood the specific challenges of raising kids alone. The first meeting I attended had about 15 parents sitting in a circle sharing stories. Some were divorced like me. Others were widowed or had partners who left.

A few had never been married at all. What connected us was raising children without the support we expected to have. People talked about managing schedules, handling finances, dealing with judgment from others who didn’t understand our situations. I listened more than I spoke that first night. But hearing their stories made me feel less alone.

Uh these weren’t people who pied themselves or complained constantly. They were finding ways to build good lives for their kids despite the hard circumstances. They laughed about small victories and supported each other through setbacks. Walking back to my car after the meeting, I felt lighter than I had in months. At the third meeting I attended, someone asked if anyone had dealt with rejection from a partner who couldn’t accept their child.

I found myself speaking before I could overthink it. I told them about Vincent calling Rosie defective, about him refusing to sign adoption papers because he saw her as a financial liability, about discovering that the man I married had been performing acceptance while actually seeing my daughter as broken. The room went completely silent when I finished.

Then a dad across the circle spoke up. His ex-wife had said something similar about their son who had autism. She told him she didn’t sign up to raise a damaged child. He understood exactly what I meant about that moment when you realize you married someone who sees your kid as less than human. Other parents nodded and shared their own stories of partners who left or stayed but withdrew emotionally.

We all recognized the same pain in each other’s faces. The pain of someone who should have loved your child choosing to see them as a burden instead. These connections reminded me that I wasn’t alone in facing rejection from someone who should have loved my child. Other parents had survived this betrayal and built good lives anyway.

Their kids were thriving. They had found new partners who actually accepted their families or learned to be happy single. They had careers and friends and moments of real joy despite everything. If they could do it, maybe I could, too. The support group became something I looked forward to instead of dreading.

A place where I didn’t have to explain or defend or justify my choices. Everyone there understood why I left Vincent. Nobody questioned whether I was overreacting or being too harsh. They knew that calling a child defective was unforgivable. They knew that some betrayals couldn’t be fixed with counseling or time.

They knew that protecting your kid sometimes meant walking away from everything you thought you wanted. 6 months after the divorce became final, my phone showed a text from Gerard asking if he could send Rosie a birthday gift. I appreciated that he maintained boundaries while showing he still cared about her. He never tried to defend Vincent or convince me to reconsider.

He just acknowledged that his brother had failed us and expressed genuine regret about it. I texted back that a gift would be lovely and gave him our new address. Part of me wondered if staying in contact with Vincent’s family was a mistake. But Gerard had been kind to Rosie before the divorce and his reaching out felt genuine rather than manipulative.

He wasn’t trying to get information or play mediator. He just wanted to acknowledge Ros’s birthday because he remembered her and cared. That felt like enough reason to maintain this small connection. I texted Gerard back that a gift would be wonderful and included our apartment address. The package arrived 3 days later in a box covered with cheerful stickers.

Inside was an adaptive art kit with thick handled brushes, textured paints, and large grip crayons designed specifically for kids with developmental disabilities. The kit included a guide explaining how each tool worked and what skills they helped develop. I sat on the living room floor reading through the materials while Rosie was at the school and found myself crying.

Not sad tears, but the kind that come when someone sees your child clearly and still thinks she’s worth this kind of thoughtfulness. Gerard had researched this. He had looked for something that would work with Rosie’s needs instead of despite them. The gift showed real understanding of who she was as a person.

I sent him a thank you message with a photo of Rosie using the paints later that evening. She had covered an entire poster board with swirls of purple and yellow, her favorite colors mixing together in ways that made her laugh. Gerard responded that he was glad she liked it and asked if he could send something for her birthday next month.

I told him that would be lovely. Ros’s seventh birthday fell on a Saturday and I planned a small party at our apartment. Her guest list included five kids from the school, mom, Brianna, and the couple from down the hall who always stopped to chat with Rosie in the hallway. I decorated the living room with purple streamers and butterfly balloons.

The cake was vanilla with strawberry filling because that’s what Rosie requested. I set up simple games that all the kids could play together regardless of ability level. The party started at 2, and within minutes, our small apartment filled with children’s voices and laughter. Rosie wore a sparkly purple dress that she had picked out herself and a paper crown that kept sliding sideways on her head.

She greeted each friend at the door with a hug and told them they looked beautiful. The kids played musical chairs and pinned the tail on the donkey with enthusiastic chaos. Mom helped serve juice boxes and kept the snack table stocked. Brianna took photos on her phone and whispered to me that this was exactly what a kid’s birthday should look like.

When it came time for cake, everyone gathered around the table singing happy birthday. Rosie closed her eyes tight to make a wish before blowing out all seven candles in one breath. Everyone cheered and she stood up on her chair to announce that all her friends were beautiful and she loved them. The parents smiled and the kids giggled and I felt my chest get tight with something that felt like relief mixed with gratitude.

I watched Rosie surrounded by people who genuinely loved her and saw the contrast with what her life would have been if I had stayed with Vincent. These people didn’t see her as a liability or a burden. They saw a joyful little girl who happened to have Down syndrome. They asked about her interests and remembered her favorite things.

They included her fully in activities without making a big deal about accommodations. This was what acceptance looked like. Not tolerance or pity, but actual acceptance of who she was. I felt grateful that I had found the courage to leave Vincent when I did. Rosie deserved to grow up surrounded by people who saw her as whole and complete exactly as she was.

She deserved a life free from anyone who viewed her as defective or less than. Watching her laugh with her friends over cake, I knew I had made the right choice, even when it had been terrifying. 6 months after the divorce became final, I decided to try dating again. Not because I was looking for anything serious, but because I wanted to test whether I could trust my own judgment after getting Vincent so completely wrong.

Matilda had been working with me on identifying red flags and understanding what healthy acceptance actually looked like. She helped me see patterns I had missed before. How Vincent had always been performative in his affection toward Rosie. How he never initiated activities with her but only participated when I arranged them.

How he talked about her in front of other people but rarely engaged with her one-on-one. These were signs I had ignored because I wanted so badly to believe he was genuine. Matilda gave me a list of questions to ask myself when meeting someone new. Did they ask about Rosie as a person or just acknowledge her existence? Did they seem curious about her personality and interests or just polite about her diagnosis? Did they make an effort to interact with her directly or always go through me? I started going on casual coffee dates through an app, being

upfront in my profile that I had a daughter with special needs. Most first dates went nowhere, but that was fine. I was practicing being honest about my life and watching how people responded. One guy seemed promising after our first meeting at a coffee shop downtown. He was a teacher at an elementary school and talked about his students with genuine affection.

When we met for a second date at a park, he asked about Rosie within the first 10 minutes. I told him about her down syndrome and about my divorce. I watched his face carefully for any sign of discomfort or withdrawal. Instead, he nodded and said his nephew had autism. He asked what Rosie liked to do for fun, what her favorite subjects were at the school, whether she had friends in her class.

He asked about her personality and her sense of humor. He wanted to know about her as a person rather than just processing the information about her diagnosis. His questions felt thoughtful instead of intrusive, natural instead of forced. I didn’t know if this relationship would develop into anything serious or fizzle out after a few more dates, but his genuine curiosity about Rosie as a complete person rather than a diagnosis felt like progress.

I was learning what real acceptance looked like compared to Vincent’s performance. Real acceptance asked questions and showed interest. Real acceptance didn’t need praise for basic human decency. Real acceptance saw Rosie first and her disability second. Whether or not this particular guy worked out, I felt more confident that I could recognize the difference now between someone who truly accepted my daughter and someone who was just saying the right words.

At work, my supervisor called me into her office and told me they were promoting me to program coordinator. The position came with better pay and the chance to develop new family support programs. I would be designing workshops and resources instead of just implementing other people’s ideas. She said, “My personal experience gave me insight that would make the programs more effective and authentic.

I accepted immediately and spent the next week planning my first major initiative. I proposed a workshop series specifically for parents navigating divorce when they had children with special needs. The emotional challenges were different. The legal considerations were more complex. The support systems needed to be stronger.

I knew this from living through it and I wanted to help other parents who were facing the same situation. The workshops launched 2 months later and filled up within days of registration opening. Parents told me afterward how much they needed this specific resource. How isolated they felt going through divorce while also managing their child’s therapies and school accommodations and medical appointments.

How guilty they felt for disrupting their child’s routine even when staying in a bad marriage would have been worse. I shared parts of my own story carefully, keeping the focus on practical strategies and emotional support. turning my painful experience with Vincent into something that helped other families felt meaningful in a way my previous work hadn’t.

It felt like taking something broken and building something useful from the pieces. Rosie started a new adaptive dance class at the community center and came home glowing every single week. She talked non-stop about the music and her friends and the teacher who let them pick their own costumes.

She practiced her moves in the living room and made me watch her performances before bed. The class was specifically designed for kids with developmental disabilities, and the teacher understood how to adapt movements while still making the kids feel like real dancers. Rosie had never been this excited about an activity before.

What struck me most was that she had never once asked about Vincent since we moved out. Not where he was or when she would see him or why he didn’t live with us anymore. She had accepted the change and moved forward with the easy resilience that children sometimes have. It told me that whatever relationship she thought she had with him hadn’t been deep enough to leave a real absence.

I realized something while watching Rosie twirl around the living room in her dance outfit. Vincent’s rejection, while devastating at the time, had actually revealed his true character before Rosie was old enough to fully understand what was happening. She had been spared years of subtle rejection and conditional love.

She would never remember Vincent calling her defective or refusing to claim her legally. She would never have to process the pain of realizing that someone she thought loved her actually saw her as broken. The timing of his betrayal, as horrible as it felt then, had protected her from deeper hurt later. She got to grow up knowing only people who loved her completely instead of learning early that love could be conditional based on how well you measured up to someone’s standards.

I brought up ending therapy at my next session with Matilda, sitting in the familiar chair across from her where I’d spent so many hours talking through everything. She listened while I explained that I felt stable now, that the worst part seemed behind me, that maybe I didn’t need to keep coming every week.

Matilda nodded and asked what made me think I was ready to stop. I told her about the promotion at work, about Rosie thriving in her dance class, about how I could go whole days without thinking about Vincent’s face when he pushed those adoption papers away. She smiled and said those were all good signs of healing, but she wondered if I’d considered monthly maintenance sessions instead of stopping completely.

The idea surprised me because I’d been thinking in terms of all or nothing. She explained that healing wasn’t a destination where you arrived and unpacked your bags. It was more like a garden that needed regular tending even after the worst weeds were pulled. I agreed to monthly sessions starting next month.

realizing she was right that the work wasn’t finished even though I’d come so far. Brianna texted me on Thursday suggesting a beach trip for the upcoming weekend, just the three of us getting away from the city for a couple days. I said yes immediately because Rosie had been asking about the ocean ever since her class read a book about tide pools.

We left early Saturday morning with towels and sunscreen packed in the trunk. Rosie bouncing in her car seat asking how much longer every 15 minutes. The drive took 2 hours and Rosie pressed her face against the window when she finally spotted the water stretching out forever. We found a spot on the sand and Rosie kicked off her shoes before I could even spread out the blanket.

She ran straight toward the waves with her arms out wide, laughing as the cold water rushed over her feet. I watched her jump over the foam and splash in the shallow parts without any fear or hesitation. Brianna sat down next to me and we both just watched Rosie play, her joy so pure and complete that it made my chest tight. This was why I’d fought so hard to protect her from Vincent’s rejection.

This was why I’d chosen divorce over staying in a marriage with someone who saw her as defective. Rosie deserved to run into waves laughing, surrounded by people who loved her exactly as she was. Nearly a year had passed since Vincent pushed those adoption papers across the kitchen table and called my daughter defective.

A whole year of rebuilding everything from scratch, of learning to trust my own judgment again, of creating a life that belonged completely to Rosie and me. We had our purple butterfly apartment that felt more like home than the house with Vincent ever did. We had Brianna who showed up for beach trips and dance recital without being asked.

We had grandma Nora who kept emergency snacks in her purse and knew all of Rosie’s favorite songs. We had my co-workers at the nonprofit who understood what it meant to raise a child with special needs because they were living it, too. We had the other parents from Ros’s school who texted to coordinate pickups and shared information about new therapy resources.

Our community was small, but it was strong. Built from people who chose to love us completely instead of from a safe distance. I wasn’t pretending anymore or hiding parts of our life to make someone else comfortable. This was our authentic life without compromise or apology, and it felt solid in a way nothing with Vincent ever had.

I tucked Rosie into bed in her purple butterfly room, pulling the covers up to her chin while she hugged her stuffed elephant. She looked up at me with her beautiful eyes and said I was beautiful. The same thing she told everyone she met. But tonight, something shifted inside me when she said those words.

I actually believed her, not because I thought I looked different or because anything external had changed, but because I finally saw my own strength reflected back in her face. I had chosen her over everything else when it mattered most. I had walked away from a marriage and rebuilt our entire life because protecting her was more important than being comfortable or avoiding conflict.

That choice had cost me the future I thought I wanted, but it had given me something better. It had given me the certainty that I would always choose Rosie, that my love for her wasn’t conditional on circumstances or convenience. She smiled at me and closed her eyes, completely secure in the knowledge that she was loved.

I sat there for a moment longer, watching her breathe, feeling grateful for the courage I’d found to leave Vincent and build this life where Rosie could just be herself without anyone calling her defective or broken.